They had been at the house on Rue Faubourg Saint-Jacques for three weeks, now. Kristoph assured Marion that the work of government on Gallifrey was getting on fine without his actual presence. He listened to reports every day from the Premier Cardinal and the Chancellor, and told her that there was nothing of significance in either. Gallifreyan politics were going through a very dull and unimportant phase just now, with nobody wanting to risk an extended debate this close to the winter solstice.

“I don’t even want to think about the winter solstice right now,” Marion commented as she reached up from her favourite seat and picked a ripe greengage from the overhanging tree. “Funny to think the snow is falling at home while we are in beautiful weather here. September in western France is a perfect month. Not too hot, only a few delightful rain showers early in the morning to freshen the air. Fantastic sunsets. It will be a bit of a shock to go back to Gallifrey in mid-winter.”

“Well, we have to drop by Cardiff in November on the way,” Kristoph pointed out. “To pick up Hillary and Claudia Jean. That will help you acclimatise. I’m glad you’re enjoying this break from it all.”

“I’m glad we can come back here any time we want,” Marion said. “Now that you’ve bought the house. It’s lovely to think of it as ours.”

“That reminds me,” Kristoph said. “Now it IS ours, there is something I want to do, that I couldn’t when we were merely tenants. You can stay there, enjoying the sunshine...”

But Marion was intrigued and followed him into the kitchen. She watched him look all around and then shove the heavy pine dresser aside. She called out to him to be careful, but he managed not to topple any of the china on the shelves. Behind it the faded yellow floral wallpaper was less faded, but Marion was startled when he took hold of a loose piece and pulled. He kept pulling until he had stripped away three whole sections and revealed a low door set into the wall behind it.

“There’s a cellar on the original plans of this house. Bound to be. This and the house next door were converted from an old coaching inn. A cellar was an integral part of such a building.”

“So why is it hidden?” Marion asked.

“Habit,” Kristoph replied. “The cellar was blocked from view many years ago. Look.” He used his sonic screwdriver as an ultra violet light. It showed up old scratches on the stone floor where the dresser had been frequently moved in the past.

“But why?” Without the light the scratches were barely visible now. The dresser had not been moved since the room was papered last. The signs of past disturbance were indistinct.

Kristoph opened the low door with one of several keys on a ring that came with the deeds. Behind it were stone steps. He went first, using his sonic screwdriver as a light and warned Marion to be careful of the second bottom stair. It was broken. She stepped carefully over it and onto the stone-flagged floor of the cellar.

It was cold compared to the rooms above, with lime-washed stone walls. It was empty except for a wooden table with a small leather bound book sitting on it.

“What’s that?” Marion asked.

Kristoph picked up the book and flipped through the pages. He smiled widely.

“Something I think you would like to look at,” he answered passing the book to his wife. “But perhaps not down here in the cold. Let’s take it back out to the sunny courtyard.”

Marion looked around the cellar again and then avoided the second bottom step as she made her way upstairs again. Kristoph didn’t come out with her straight away. She was settled beneath the greengage tree with the mysterious book before he came out with a jug of home made lemonade.

“It’s a sort of story... a true story... written by the lady who lived in this house during the war... during the occupation of France by the Nazis,” she said, showing him the handwritten pages. “It’s in French, but I can read it easily. That must be the TARDIS helping me out. I was only really average at French in school. It’s called ‘La Miracle de Rue Faubourg Saint-Jacques.’”

“Good title,” Kristoph said, pouring two glasses of lemonade.

“You know what it’s about, don’t you?” Marion said. “You read it already. When you flicked through the pages. It’s... I mean... it’s about a bad time for people here. If there’s a sad ending, I’d rather not read it at all.”

“There’s a happy ending,” Kristoph replied. “And I think you’ll like it.”

“The woman who wrote it,” Marion continued with a smile. “Her name is Marianne. And... Oh! Her husband is called Cristophe. That’s an amazing coincidence.”

“Yes, it is. Though Marianne is a common name in France. As well as being the personification of the nation itself.”

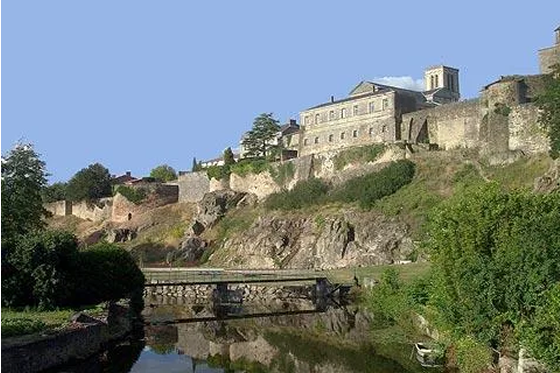

The first pages of the story related how Marianne D’Astier who kept house and baked bread to feed the men who piloted the small coal boats that went up and down the Thouet to Saumur where that meandering river whose name derived from the Gaelic for ‘tranquil’ met the busier Loire and carried on all the way to St. Nazaire on the Atlantic. Her husband, Cristophe, who was one of those pilots, had become involved in the Resistance to the Nazi invasion, opening their home to those escaping the enemy. At first it had been people they knew, neighbours such as Monsieur Levy and his wife from two doors up, and then Monsieur Caen and his family from the Rue de la Vau Saint-Jacques. The Caen family had lived there for many generations. They were hand loom weavers who worked in the attic rooms as hand loom weavers had done on that street for four hundred years. Nobody minded that they were Jewish. All that meant was that they were busy on Friday evenings when their neighbours were at leisure.

Nobody believed the things that the Nazis said about Jewish people, least of all Marianne and Cristophe who opened the door to them late one night and let them stay in their cellar until they could be brought down to the river and hidden in one of the coal boats heading to La Rochelle.

After a very short while, there were no Jewish families in Parthenay. Those who hadn’t gone away by river or by some other means had been taken away by the Germans. Nobody asked what would happen to them. Marianne hoped that Monsieur and Madam Levy were safe, and Monsieur Caen and his wife and children. She tried not to think about the alternative.

There were others who needed their help. Monsieur Bellard and a Madamoiselle Murat who were both syndicaliste. That word was translated as trade unionist in front of Marion’s eyes. They had come to the attention of the German authorities in the town and had run for their lives before they were arrested.

And then there were any number of British and later American airmen who were lost over France and needed help to get to the coast and a boat.

At any time there were at least two or three extra mouths to feed in Marianne’s cellar. She did her best for them. Mostly she baked bread. It was the easiest food to prepare. Sometimes she managed to get eggs or a little cheese, but mostly she baked bread.

Near the end of the summer of 1941, three men were in the cellar. There was Monsieur Olivier and Monsieur Petron who were inverti...

That word didn’t translate. Marion looked up from her reading. Kristoph said it was a French slang word for homosexual.

“Marianne probably didn’t realise that the word implies that they are ‘wrong’. It is usually only used as a term of abuse. But the word the Nazis used for them in that time was even nastier.”

There was an American airman in the cellar, too. Marianne had thought at first that he was inverti, too. But the way he flirted with her in a rather dashing, charming way when she brought the food to them made her wonder about that.

“He sounds like Captain Harkness,” Marion commented. Kristoph laughed and agreed.

Then Marion read on to an incident that frightened her French namesake.

It was an ordinary incident in many ways. She was coming home from the shops over the Pont Saint-Jacques. She had a large sack of flour in her basket. She put it down under the ancient Porte while she found her identity card to show to the German Hauptgefreiter who checked everyone coming and going over the bridge.

“That is a heavy load, Fraulein,” said the Hauptgefreiter as she put her card back in her pocket and bent to lift the basket. “Let me help you.”

“I don’t need any help from you,” she replied coolly. “And I am a married woman. The correct term in your language is Frau, and in mine, Madam.”

“I come from Dusseldorf,” the Hauptgefreiter said. “There it is still common courtesy to offer help to a woman with a heavy load.”

“Then go back to Dusseldorf and help German women,” Marianne answered. “If you are finished with me, I will be on my way. I have bread to bake.”

“A lot of bread,” the Hauptgefreiter commented. “Have you a large family, Madam D’Astier?”

Marianne was surprised that he had remembered her name from her identity card and disturbed by his remark about the volume of flour she was carrying.

“I make bread for the boatmen who bring coal from Saumur and take made goods to the port along the river. My husband is one of them. They have all been registered and approved by your commandant.”

“I am sure that is so,” the Hauptgefreiter said. “I apologise for delaying you, madam. And I regret that this uniform I wear makes you reluctant to let me help you with your load, or to have an ordinary, pleasant conversation.”

“Good day to you,” Marianne said in reply. She walked carefully across the bridge. She felt as if she wanted to run, but the basket was too heavy and in any case running from a German guard was the very thing to make them suspicious.

She told her husband about the incident that evening. He was thoughtful.

“Of course, most of the ordinary German soldiers are conscripts. He may not want to be here any more than we want him here. But it would not do for him to be familiar with you. And I don’t like that he noticed you buying flour. Next time, buy from Monsieur Pichon on Avenue Wilson. Then you don’t need to cross the river on your return.”

“Monsieur Pichon charges twice as much and he looks at me in an inappropriate way,” Marianne pointed out. But she knew he was right. It was better to vary her routine and not draw the attention even of a seemingly pleasant and disarming German soldier.

Sometimes she had no choice. She had to cross the Pont Saint-Jacques in order to get to other shops and to go to church on a Sunday. She met the young Hauptgefreiter several times in the week that followed. He was always pleasant to her. She remained cool towards him. She felt bad about it. She was sure he was a nice young man, if only he was not a German soldier. But quite apart from the fact that she still had three men hiding in her cellar, she would not want her neighbours to think she was friendly with one of the enemy.

The three men in the cellar were a problem. The boat that was supposed to take them down river had broken down and they had been forced to remain there, living on her home baked bread. Of course, nobody had an inkling that they were there. In many ways they were safer hidden quietly in the cellar than when they broke cover to go to the boat. But Marianne and Christophe were increasingly nervous about their charges.

Then one evening when Christophe was working on his boat and Marianne was taking freshly baked bread from the oven, there was a disturbance. She screamed as the front door of the house burst open and heavy feet rushed through the hallway. Four soldiers and an Oberleutnant in charge of them came into the kitchen. Marianne noticed that one of the men was the Hauptgefreiter from Dusseldorf. He avoided her gaze.

There was a woman with them - Madam Gionet from three houses away. She looked at Marianne once and then turned her face away. The Oberleutnant asked her to confirm what was wrong with the kitchen of Madam D’Astier.

Madam Gionet looked around once and then pointed to the dresser with the china arranged on it. She waved her hand at the floor. Marianne’s heart sank. There were scratch marks where the dresser had been moved every day when they took food to the men.

Two of the solders were ordered to move the dresser. They did so clumsily. The china slid off the shelf and smashed on the stone-flagged floor. But Marianne didn’t care about china any more. Her thoughts were on Monsieur Olivier and Monsieur Petron and the American airman who had not told her his name because he did not want to burden her with information that the enemy could extract from her if she were questioned.

“She wasn’t even thinking about herself, or her husband,” Marion said. “Only the men she had been hiding. But they were in such terrible trouble.”

Marion knew there had to be some sort of good outcome to this story. She was reading it in Marianne D’Astier’s own hand and besides, the title was ‘La Miracle de Rue Faubourg Saint-Jacques.’ Even so her heart raced as she read Marianne’s description of the Oberleutnant going down the cellar steps with Madam Gionet, followed by three of the soldiers. The Dusseldorf Hauptgefreiter had been told to watch Marianne. She had a moment of satisfaction when it was obvious that Madam Gionet had tripped on the broken second last step, but it could only be moments after that before the men were arrested – or worse, killed on the spot. She almost expected a burst of gunfire to settle their fate. Her own fate, and that of Christophe, hung in the balance.

Then the Oberleutnant shouted angrily. Marianne only understood a little German, but she guessed from the few words she did understand that the cellar was empty. There were no men hiding down there. Just how that could be, she didn’t understand. There was no way out except through the door which couldn’t be opened from the inside when the dresser was against it.

But she had little time to think about it. To her utter surprise the Dusseldorf Hauptgefreiter grabbed her arm and pulled her towards the back door.

“Come, madam, while there is a chance,” he said. Marianne didn’t hesitate. She ran with him out into the courtyard and over the wall that separated her courtyard from the garden next door with a greengage tree growing close by. There was a gate that led out onto the alleyway behind the houses. They moved quickly along it, heading towards the river. But Marianne knew the alleyway did not go all the way. Sooner or later they would come back to Rue Faubourg Saint Jacques, and there were Germans there. They would be caught.

Then a man stepped in front of them in the gloomy alleyway. Marianne gave a soft cry of fright. The Hauptgefreiter drew his gun. But the man stepped closer.

“Your husband is waiting at the boat, Madam D’Astier. Put this on and walk quietly. You will be safe.”

He hung a medallion on a piece of ribbon around her neck. He looked at the Hauptgefreiter, who had lowered his gun but was still tense.

“I think you have nothing to stay here for,” the man said to him, handing him another medallion. He put it over his head. The man led them to the end of the alleyway and back to Rue Faubourg Saint-Jacques. German soldiers were hammering on doors, forcing their way into houses, searching for Madam D’Astier and a renegade from their own ranks. But to their surprise, they walked down the street unchallenged all the way to the river where Christophe D’Astier’s boat, named Marianne, was waiting. Neither understood why they or the boat were not being surrounded by the Germans. They didn’t understand why they were alive.

“Get this man some civilian clothes,” said their strange saviour when they stepped aboard the boat. “He is no longer a soldier of the Wehrmacht.”

Christophe D’Astier accepted the stranger’s word on that. He had already accepted his word that his boat was safe and that they would have no trouble reaching Saumur by river even with the German army on high alert and perfectly aware of which boat they were looking for.

“We’ll never see our home again,” Marianne said as the boat slipped downstream away from Parthenay.

“Yes, you will,” said the stranger. “The war will not last forever. You and Christophe will go back to the Rue Faubourge Saint-Jacques. Monsieurs Olivier and Petron, you too will see Parthenay again. Hauptgefreiter Baecker, you will return to Dusseldorf in peacetime. And the Group Captain’s family in Iowa will welcome him home in the course of time. Be patient. And be prepared for discomfort in the immediate future. When we reach Saint Nazaire there is a tramp steamer heading for neutral Ireland with a cargo of live chickens. But you will be safe. I can promise you that much.”

Marion looked up from reading the handwritten story. She studied Kristoph’s face for a long minute, but it was inscrutable.

“It’s you,” she said accusingly. “You went there. You gave Marianne and Hauptgefreiter Baecker personal perception filters. You did something similar to the boat – you must have taken the men from the cellar in the TARDIS and then put it aboard the boat and extended its chameleon cloak so that the Germans didn’t see it.”

Kristoph’s mouth turned up slightly at the edges.

“When did you do it?” she asked.

“While you were reading the first pages of the story. The lemonade was already made. It took only a minute to take the TARDIS back in time and do what had to be done, then come right back here.”

“I wish you’d let me come with you. I’d have liked to have met them – Marianne and Christophe. I think... If we were in the same position, I hope we would have done the same, no matter how frightening it must have been.”

“I certainly would,” Kristoph said. “But then I have training and experience. It takes my breath away when I think about two ordinary people like them risking all for the sake of others. That’s my definition of heroism. That’s why I thought they deserved a little help.”

“But if it was here in the book all along, how could you have just...” Marion thought about the paradox for a few moments before giving up and accepting that anything was possible for a Time Lord.

“If you want to take a little trip before tea time, come on with me now,” Kristoph said to her. “There’s something I’d like you to see that brings the story to a pleasant ending.”

Marion was reluctant to leave the sunny courtyard, but she followed her husband into the TARDIS. A very short time later they stepped out into a hot dry climate that surprised her after the temperate French autumn. There was a flawless blue sky above a garden with trees growing in the sandy soil. Kristoph brought Marion to a wall where names were inscribed and easily found the names of Christophe D’Astier and Marianne D’Astier.

“This is the Garden of the Righteous at Yad Vashem in Jerusalem,” Kristoph explained. “Here non-Jewish people who have risked their lives to help Jews are honoured. Marianne and Christophe were nominated for inclusion by Monsieur Levy and Monsieur Caen who were among the first people they saved.”

“So they made it? Marianne didn’t know if they had. I’m glad.”

“So am I. The rest of the story tells how they lived out the war in Ireland and came back in 1946. But the house didn’t feel like home any more. They put it in the hands of an estate agent and returned to Ireland where they had made a new life for themselves. Marianne wrote the story of her last days in the Rue Faubourg Saint-Jacques and left it for anyone who might be curious enough to look behind the dresser.”

“What about the others?” Marion asked. “Were you right? Did they all make it?”

“They did. All of them. Even the Group Captain who got back to England and rejoined his squadron. He made it through the war and went home to America.”

“Thanks to you. If you hadn’t been there, they would all have died, wouldn’t they?”

“I have no cognisance of alternative timelines,” Kristoph replied. “That is what happened. There is no need to dwell on other possibilities.”

“Yes,” Marion agreed.

“Let us pay our respects at the memorial to those who were not so fortunate in that terrible time in Earth’s history. And then we shall return to Parthenay in time to enjoy the best of the autumn evening. We really must think about returning to our Gallifreyan winter soon, so let’s make the most of it.”

“We still have Cardiff in the rain to acclimatise us,” Marion reminded him.

|

|

|