“It is the strangest thing I ever saw,” Julia said as she looked up at the steel grey sky. On the planet of Utepi Ionn that was not a poetic way of describing a sullen, cloudy day. The sky really WAS made of steel.

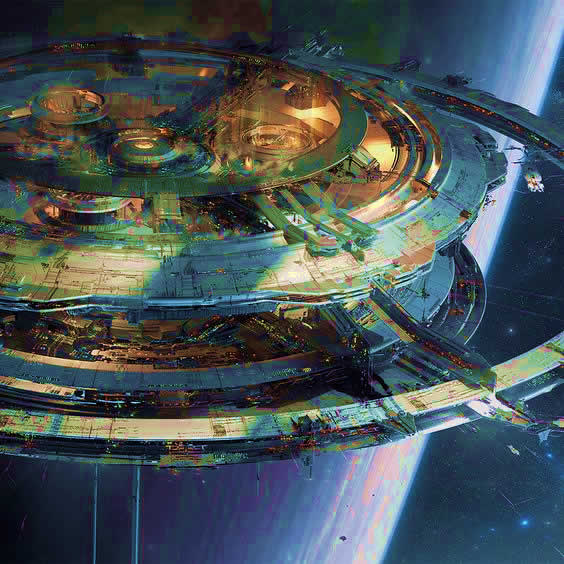

“It is an engineering miracle,” Chrístõ told her. “They have an entire continent, nearly half a hemisphere, encased in an artificial sky to protect it from the dangerous rays of their sun. It is amazing.”

“I don’t like it,” Camilla said. She looked up once then looked away. “It just isn’t natural. I couldn’t LIVE here.”

“I’m not sure I could, either,” Kohb added. “I love the wide open plains of Gallifrey.”

“Give me the grasslands of Haeolstrom,” Camilla continued. “Riding a barely tame stallion horse against the wind, feeling as if I could ride to the horizon and not be tired.”

“I’ve never seen a horse,” Kohb said. “Only in pictures. We don’t have them on Gallifrey.”

“I don’t think they have them here, either,” Chrístõ noted. “They DO have enormous amounts of security, though.”

He sighed deeply and turned to direct the porters who were manhandling his most important piece of freight. Utepi was a strangely paranoid planet. Even the diplomats heading to the Conference to discuss Utepi’s admittance to a trade federation that would offer huge financial gains to the planetary government were subjected to stringent security. No personal transport was allowed on or off the planet. They had travelled by TARDIS as far as a spaceport on the edge of the solar system and from there they were brought by shuttle to a designated orbit around the planet and then transmatted to the immigration control centre. But Chrístõ had refused to leave his TARDIS on either the spaceport or the shuttle. He had set the internal gravity so that it only weighed a couple of metric tons and it had disguised itself as a large packing crate. It was coming with them as the oddest piece of diplomatic baggage in the history of diplomacy. But it was most certainly coming with them.

From the immigration centre where they had spent several dull hours having their identities confirmed several times, they crossed a concourse above crowded freight yards and into a huge railway station with a roof that seemed like a second, lower version of that strange sky. Personal transport was discouraged on the planet, too, and everyone travelled by train. It was a huge complex, and from the main entrance to the platform where they were to board their train they passed three times through security checks as stringent as the immigration control.

Chrístõ was starting to have fond feelings for the Gallifreyan Civil Service. In comparison they were laid back and relaxed.

Quite apart from the detailed examination of the bill of lading for his ‘freight’ the four of them travelling together was making things difficult. They came from three different planets and, since he himself was half Human and Kohb pureblood, they constituted four distinct species by local definition at least. This was a cause of consternation every time they showed their papers. Interplanetary harmony didn’t seem to be a concept they had heard of here on Utepi Ionn. Chrístõ was strongly wondering why they even WANTED trade relations with a galaxy they seemed to hold in suspicion at best and contempt at worst!

“Why can’t the first one radio through and tell them that they’ve cleared us?” Julia complained wearily as they approached what they hoped was the LAST such barrier.

“Bloody-minded bureaucracy,” Camilla answered her. “I’ve seen worse. Chrístõ, have you ever visited Alpha Unutau?”

“My father mentioned it once. All visitors to the planet are accompanied by security guards whenever they leave the designated hotel zone. You have to show a passport and visa just to go into a shop. I won’t even begin to describe the procedure for entering and leaving the public lavatories. NOT on my list of fun places to take Julia.”

“Neither is THIS,” Julia pointed out.

“No, it’s not,” he admitted. “It’s a pity this came in the middle of your holidays. But I’m a working man, now. And I have to do these things.”

“I’m proud that you’re a diplomat,” she told him. “My aunt is REALLY impressed, too. Remember how excited she was at having you AND Camilla in the house. But really, it’s a boring kind of job if you have to come to places like this.”

“It’s not always places like this. The conference is only a three day one, anyway. And then we’re going to meet Penne and Cirena at the coming of age reception for the Crown prince of Ryemym Ceti. You’ll have a chance to wear all of those gowns you had made on Gallifrey. That should be enough glamour to keep you going until the Christmas holidays.”

“When I’m stuck wearing school uniform!” she grimaced.

At last, the authorities seemed satisfied with them all and they were passed through to the busy train platform. Julia stayed close to Chrístõ and Kohb put a protective arm around Camilla as they threaded their way through the crowds, the TARDIS freight causing some annoyed remarks as the porters pushed through, not caring much how many ankles they caught with the trolley it was mounted on.

“The train is delayed,” Chrístõ noted as he looked up at the interactive arrivals board. “Half an hour. And I don’t think the concept of waiting rooms or refreshments ever entered into anyone’s heads here.”

“Oh, to hell with it,” Camilla said before shimmering and reverting to Cam in a light sweatshirt and white slacks with comfortable loafer shoes. “That’s better,” he said. “Camilla’s footwear is too uncomfortable for travelling.”

“You’d better give me your OTHER travel pass,” Chrístõ told him. “Before the NEXT security check.” He noticed, and so did Julia with a smile, that Kohb still had his arm around Cam.

“I’ll be attending the conference as Cam, anyway,” he said as he swapped credentials.

Kohb said nothing, but his arm moved from his shoulder to his waist. His slow but certain courtship of Camilla continued by mutual agreement. And as far as he was concerned, the courtship didn’t stop when she became a man for reasons of business or of comfort.

And Chrístõ, looking at them, couldn’t think of a single reason why not. They LOOKED perfectly right together. Cam was a very handsome young man with a soft vulnerability to his features that was actually misleading, as anyone who opposed him in a debating chamber knew to their cost. Kohb was good looking in his own way. They were a beautiful couple in either permutation.

Nobody around them seemed to be especially concerned by what in some societies would be a scandalous public display of abnormal affection. The other groups of travellers to the conference were not likely to comment. They came from such varied societies themselves that a group of humanoids together was mundane, regardless of who was holding hands with whom.

As for the indigenous population, he had never seen such an indifferent lot. They were humanoid, too, and their dominant colour was grey. They had grey skin and hair and they all wore grey clothes, either suits for the office or overalls for manual work. They all had glum expressions, or rather, no expression at all. They were just there, waiting for the same late train.

Living under a steel sky was not, Chrístõ thought, especially good for the population. He had only been on the planet a couple of hours, and most of that waiting for things to happen. But if the rest of the population was as frankly miserable as this lot, then it wasn’t much of a life.

As they waited for their delayed train there was an influx of uniformed guards onto the platform. They lined up along the edge, pushing the waiting passengers back.

“What’s happening?” Chrístõ asked the nearest native Utepian.

“Grand Marshall Braigr Rho’s train is passing through,” the citizen answered. “We are honoured.”

“Are we?” Chrístõ raised an eyebrow in question. Nobody looked especially honoured, not even the man who said it. The sound of a train arriving grew louder. It made no difference if it was a steam train at Charing Cross in 1860 or an electric train a century later, or a sleek hydro-train in 52nd century Tokyo. Nobody had ever succeeded in making the arrival of a train into a station anything less than a noisy event. This was no exception. The sound of the great iron beast, the smell of diesel, overwhelmed everything else.

It was the most pointless time to mount a protest. The two men who suddenly unfurled a banner and ran at the line of soldiers would never have been heard even if they had got close enough for the Grand Marshall or anyone on the train to notice them. As it was, their protest was short and pointless. By the time the train passed by their bodies were lying under a hastily spread tarpaulin, the end of their banner flapping in the displaced air.

“It’s all right,” Chrístõ told Julia. His instinct had been to protect her from the sight of sudden and pointless death. She hadn’t actually SEEN it happen, because she had turned her face away, but she knew it had. And it upset her.

It upset them all. He looked around to see Cam and Kohb clutching each other tightly and looking stunned.

And yet around them nobody else seemed disturbed at all. There was no expression of shock or revulsion, or even of satisfaction at the demise of a dangerous pair of rebels. It was as if the incident had never happened. The soldiers moved away, taking the body with them. One of them bundled the banner up and took that, too. Nobody commented.

“You get SHOT here for protesting,” Kohb pointed out as they sat together on the train, Julia in the window seat with Chrístõ beside her and Cam and Kohb opposite them. Chrístõ tried to coax Julia to drink the orange juice from the bag of travel supplies he brought with them on this comfortless journey. She drank it because she was thirsty, but without enjoyment.

“NOBODY even looked shocked.” Julia said.

There were three possible reasons for that. EITHER the people were so self-absorbed and indifferent that they really DIDN’T care, or they feared reprisals if they DID show any reaction.

Or they had seen it so often they were conditioned to it and didn’t comment.

“What did the banner say?” Chrístõ asked. “I didn’t see it.”

“Open The Sky,” Kohb answered.

“That’s a bit cryptic,” Cam mused. “What do they mean?”

“I can’t imagine anyone is going to tell us,” Chrístõ said. “And I suppose… I hate to say it, but the internal politics of this planet are NOT what we are here for.”

It went against the grain, but it was true. His reason for being here was a trade conference. It was not his job to make things better for the grey people who lived here, except in the indirect way that better trade should make for a more prosperous people generally.

It chafed him. It was the hard part about learning to be a diplomat, to do the work his father did so very well, the job he had wanted to do ever since he was old enough to accompany his father on trips like this one and to sit in the gallery watching him at work.

As a boy of fifty, watching his father seal a peace treaty between warring planets, he had wanted nothing more than to follow in his footsteps. But he thought about how he had been able to make a difference on planets like Pernandria, where he had reunited the ‘wild flowers’ with their families and effected a change in their whole society for the better. As an Ambassador he was able to talk to presidents and premiers as equals and sign treaties and trade agreements. But his powers to effect real change for the ordinary people were limited. He wondered sometimes if he wouldn’t rather be the ‘freelance’ troubleshooter he used to be.

Though he wasn’t sure WHAT he could do to help the people of Utepi Ionn. Or even if they WANTED to be helped.

He sighed and stretched his long legs as far as he dared without banging into Kohb’s legs under the narrow table. It was not exactly executive travel, he thought, grimly. The diplomats were travelling in the same carriages as ordinary citizens and with the same basic provision of a not especially well padded seat and some rudimentary toilet facilities at the end of the carriage. He had not yet needed to test those out but he wasn’t too hopeful.

“I feel slightly homesick for British Rail,” he joked. But since none of his companions had travelled on an Earth train in the 20th century the joke fell flat.

He sighed and looked out of the window. They had left the main city behind and were travelling through a strange sort of countryside with fields of grain grown under artificial sunlight provided by huge lights on great gantries, a bit like floodlights at a football ground on Earth, except presumably matching more closely natural sunlight.

That answered a question Chrístõ had been asking himself since they arrived on this strange planet. Just HOW did the population feed themselves. But it must be expensive doing it that way. And this didn’t strike him as a society where anything came cheap to the population - except life itself.

Herested his head against the seat back and let his mind reach out around the railway carriage. He looked at the thoughts of the people around him.

The overriding thought of them all was of reaching their destination and doing their day’s work. They were commuters. They went from the population centre to the work centre by train every day. And home again at night. They kept their families fed and the rent paid and if they were unhappy they didn’t say so out loud.

But underneath the immediate issue of getting to work and getting through the day without attracting the attention of the foreman, was a seething brew of discontent. The food produced by such methods WAS, indeed, expensive. And more expensive every month, while wages were frozen and sometimes cut. The travellers looking out of the window looked covetously at the food.

Others looked up at the steel sky and their thoughts were the thoughts of prisoners denied the sunlight. Worse even. A line of Earth poetry on just that subject drifted into his mind.

I never saw a man who looked With such a wistful eye Upon that little tent of blue Which prisoners call the sky.

He never really appreciated the meaning of those lines of Oscar Wilde’s epic poem until he looked up at the steel sky through the eyes of one who had no TARDIS to escape from it in. It gave them life, to be sure, on a planet that would otherwise be lifeless. But the quality of that life was questionable.

And there were those whose thoughts drifted from the food and the sky to that pitiful act of rebellion earlier. “Open the Sky”. It was, as he had almost guessed, a campaign to have the steel taken away and let them take their chances with the radiation. Foolish, everyone was thinking. Yet, at the same time, there was something almost like sympathy for the idea. At the back of people’s minds, they were thinking that even a year of real sunlight, even if they died of skin cancer by the end of it, was worth more than a lifetime in this oppressive twilight.

Foolish, Chrístõ thought. But understandable. And he had the answer to his most important question.

This WAS a society badly in need of change. The people WERE oppressed in several ways. They were trapped in a cycle of high prices and low wages with nobody prepared to speak up for their lot. They were ruled by a militaristic government whose answer to even the feeblest protest was quick death and even quicker removal of the source of the trouble.

And they lived under a grey steel sky that in itself oppressed the soul so that it was a wonder any of them even had the will to protest about anything.

And it was his job to negotiate a trade agreement that would hardly scratch the surface of the problem.

Yes, the constraints of diplomatic life chafed badly. His instinct was to HELP the people, not talk with the government.

But what could he do?

“Christo,” Cam said to him. “Sometimes you have to fight the battles you can win.”

He looked up, startled. He knew Cam had no telepathic powers. But he also knew he was an astute and experience diplomat. He knew how to read other people’s faces, and his face must have been giving away too much.

“I hate that expression,” he responded angrily. “Fight the battles you can win? Apart from being cowardly, it is too easy as a get out from difficult situations. We can’t win, so lets not try. No, I won’t accept that. And I don’t believe my father would, either. Not as a diplomat, or in his former career as an agent of our government in situations where diplomacy failed. Nor would Master Li whose soul lies within mine.”

“Ok,” Cam replied calmly. “Fight the battles you know you have a chance of not losing, then. Chrístõ… you saw what happened back there at the station. Your life is worth more than a futile gesture.”

“My life is not worth more than anyone else here,” Chrístõ answered.

“Yes, it is,” Cam told him. “You are a wonderful, kind, generous, beautiful soul who cares even about these dullards who can’t even fight for themselves when they surely know they are being exploited and used. Chrístõ, they don’t DESERVE you fighting for them. If that pathetic attempt at a protest was the best they can do.”

“Cam is right,” Kohb told him. “There is nothing you can do and it wouldn’t even be appreciated if you did.”

“You’re both missing the point,” he replied. “I…”

But he never got around to making his point. There was a screech of brakes and the train lurched towards an ungainly and unscheduled halt. The indifferent Utepians found voices to cry out in fright as the buffers between the carriages collided and everyone was thrown forward and then backwards in their seats.

“Did we crash?” Julia asked fearfully as the train finally stopped moving.

“No,” Chrístõ answered her. “A crash would have been more painful. Is everyone all right?” Cam was rubbing the back of his head having hit it on the seat back. Kohb was nursing a bruised elbow, caught against the edge of the table, but they were relatively unscathed. Chrístõ began to stand to see if anyone else in the carriage needed first aid but before he could do anything Julia let out a scream. One that was echoed up and down the carriage.

There were men outside the train, with guns. They were forcing open the doors and boarding it. Chrístõ dropped back down in his seat.

“We’re being hijacked,” he said. “Everyone keep calm. This is either a robbery or possibly political…” He reached and pushed Julia’s silver pendant, the one he gave her, with the constellation of Kasterborus marked out in diamonds, inside her blouse and pulled the collar up over the chain. Hopefully it would not be seen if robbery WAS the motive. He didn’t want that precious heirloom stolen. He slipped off the gold wedding band he wore, his father’s wedding ring from his first marriage to his mother. He pushed it into the lining of his leather jacket where it wouldn’t be found even if he was searched. Cam followed his example with his watch and rings.

Kohb didn’t own any jewellery and his watch was inexpensive.

But when the gunmen came into the carriage it quickly became obvious that robbery wasn’t their objective.

“The People For Open Skies are in control of this train,” shouted a man in black clothes who held up two fearsome looking guns in rather a showy way. “Do as you are told and you won’t get hurt.”

And his comrades came up the carriage. They were looking, Chrístõ soon realised, for the delegates heading for the conference. A dozen or so of them were harried and shouted at as they were brought through from a carriage further back. Meanwhile, there were screams from the carriage directly in front of this one. Chrístõ glanced out of the window and saw that the Utepians in that carriage were being ordered off the train.

“You, also,” they were told by a man with a gun as he identified them as alien visitors. “Move.”

“We’re coming,” Chrístõ assured him. He took hold of Julia’s hand and lifted her from the seat gently. He kept a tight hold on her as they were urged through to the carriage that had been emptied. He noticed that the next carriage was the freight car where the TARDIS was. Beyond that, was the locomotive.

At least fifty diplomats and their spouses and aides were pushed into the one carriage. They were made to sit three to a seat. Chrístõ slid Julia onto his knee and held her tightly as they were pushed into a place next to a scared looking Delphian woman who was fingering at a prayer bracelet on her wrist and murmuring the prayers feverishly. Cam and Kohb were on the other side of the aisle, holding onto each other tightly.

“Please,” the Delphian woman begged as one of the hostage takers passed them by counting heads. “I am not a diplomat. I am just a maid. I do hair and make up and prepare soothing drinks for the Delphian Ambassador. I am not important. Let me go.”

“If you are not important, we will kill you first, to prove we are not bluffing,” the hostage taker answered, leaning past Chrístõ and Julia to wield a knife threateningly.

“You may do that,” Chrístõ said. “If you are utter cowards. But if you do, you will lose any credibility your cause had in that moment. Go away and leave this woman alone.”

The hostage taker looked at Chrístõ for a long moment before swearing at him and standing up straight. He looked fierce and determined now, but for a moment Chrístõ had seen the fear and uncertainty in his eyes.

There was a bumping movement and those of a nervous disposition raised their voices. But it soon became clear that nothing startling was happening. The carriage had been uncoupled from the rest of the train. They were soon under way again, taking a side track that brought them to what looked like the railyard of a disused mine. That was just a change of scenery, though. Nothing more.

“Are you going to tell us what this is all about then?” the Calibrian Consul demanded near the front of the carriage where the apparent leader of the group stood.

“Your governments are being informed of what this is all about. All you need to know is that we mean business.”

“It is outrageous,” replied the Olumnia VIII Ambassador. “We are ALL visitors to your world. And you behave this way.”

“Of course you are visitors. No Utepians have been harmed. They will no doubt be docked a morning’s pay when they don’t get to work. And that is unfortunate. But we would not harm any citizen of Utepia. But why should we care about any of you? Well fed, rich aliens who come to talk TRADE with the dictator who keeps the people as slaves to his regime. You who live beyond the steel sky where you can breathe good air.”

“You don’t know the air on Olumnia,” the Ambassador to that planet retorted with a hollow laugh. “This place is a garden spot in comparison.”

“Shut up,” the terrorist leader replied. But he had opened the floodgates now. He was the captor of people who made their living talking. They were their own hostage negotiators. Chrístõ listened carefully to the replies forced from him. It became clear that these were a slightly better organised version of the futile protesters at the station. Their objective was to rid themselves of the dictator, Braigr Rho. And there was some logic to that. Rho was, apparently, the one who ordered the price rises and restrictions on the amount of food available, while at the same time cutting wages and demanding higher productivity. He was pushing the people to breaking point and these ones had broken.

All that was the claim of revolutionaries everywhere, of course. They wanted the government brought down and a new regime in place. But these had another agenda. The source of the REAL problem was not, they claimed, Braigr Rho as such, but that oppressive sky which stood over them all.

“Well what are any of US supposed to do about that?” Cam asked, joining in for the first time in the impromptu debate. “The steel sky protects you from dangerous rays.”

“Does it?” the leader demanded. “We were told that, centuries ago, when it was put in place.”

“WHY exactly was it put in place?” Chrístõ asked. “And when?”

“Four centuries ago,” the leader said. “We had a war. The eastern continent, this one, destroyed the western alliance by use of devastating weapons. There were no survivors. Nothing lived on the western side of the planet when it was over. But we had destroyed the Mantle. It was a protective layer in the atmosphere that deflected the harmful rays of the sun while allowing the safe, good warmth and light through. And that was destroyed. The same scientists who had developed the Neutric bombs that gave us victory developed the steel sky to protect us instead. But it became our prison. Four centuries, countless generations have been born underneath it, never knowing sunlight, their spirit crushed by its constant presence and their lives subject to the whim of a dictator.”

“Four centuries?” Chrístõ did the maths in his head. What they were talking about when he mentioned the Mantle was something like the ozone layer that Earth and Gallifrey and most other oxygen rich atmospheres had. Earth was another planet that came close to losing that natural protection through its own short-sightedness. Utepi was an object lesson to them all.

But if it all happened four centuries ago?

Chrístõ moved in his seat slowly. He slid Julia off his knee and stood up. He raised his hands to show he was no danger to anyone.

“I can’t change your government,” he said. “Nobody here can. We came here for a trade conference. And I don’t think whether we make it or not it is going to do a lot for the ordinary people of Utepi. I rather suspect it will just let the Grand Marshall buy a bigger train. You’re going to have to deal with him some other way. But if you want to do something about the sky, I might be able to help. If you will trust me.”

“Why should I trust you?” the leader demanded. “And HOW could you help?”

“Just trust me,” he said. “Come with me into the freight car behind you.”

“You have got to be…” The leader looked at Chrístõ’s eyes as he stepped closer to him. “What can you…”

“I can be decisive,” Chrístõ said. “All that stammering and incomplete sentences doesn’t do much for your credibility as a terrorist leader. But I don’t give you much more than an hour anyway. Braigr Rho is a military dictator. He has armies at his command. And you’re not exactly hidden here. And there’s what? Twenty of you?” Do you not think his stormtroopers will be here very soon to kill the lot of you?”

“We’re ready to die for our cause,” the leader said. And several of his men repeated the mantra of would-be martyrs everywhere.

“Yeah, I’m sure you ARE,” Chrístõ retorted. “We saw a demonstration of your readiness to die back at the station. How often do people sacrifice themselves that way? What DIFFERENCE does it make? Its no use being a political martyr if nobody cares. When you’re all dead, will anyone even remember your name? Will they KNOW your name? I suppose Rho controls the media? He will suppress all mention of what happened here except that there was a minor incident on the train which delayed the start of the trade negotiations. You won’t go down in a blaze of glory. You’ll just go down. And I’m worried about how many of these innocent people go down WITH you. Rho’s troops don’t shoot first and ask questions later. They just shoot first and then shoot anyone who ASKS the questions. So if you REALLY want this to be more than a meaningless gesture that does nothing in the long term except mess up my chances of seeing my girlfriend again after her guardians find out that I brought her into a bloodbath, TRUST me.”

The leader looked at him again. Everyone looked at him. There was a glint in Chrístõ’s eyes that surprised even his friends. Cam nodded with satisfaction. Chrístõ had a way out of this. It wasn’t the diplomatic way, but he WAS fighting a fight he had a chance of winning now, and everyone’s chances of surviving were improved if the terrorists would just take his word.

“Just YOU. None of your friends,” the leader said at last. He beckoned two of his people to flank Chrístõ and two more came forward to take command of the hostages.

“Julia,” Chrístõ said. “Sit tight and be brave like I know you can. Look after the lady beside you. She’s really scared because she has never been in a situation like this before. You have, and I know you have the courage.”

At the door, Chrístõ turned to the ones who were in charge now. He noticed their fingers hovering on the triggers of their guns.

“If ANYONE here is harmed while I am away I will forget that I am a pacifist and I will make you SUFFER before you die.”

Nobody looking at his face right then doubted any part of that statement except the part where he said he was a pacifist. His soft brown eyes hardened and his facial muscles were set, his mouth a thin line of contempt for inept terrorists with half-baked ideas that were guaranteed to get EVERYONE killed without achieving anything.

“What IS your name anyway?” Christo asked as he walked ahead of his captors into the freight car. He could see the TARDIS inside a wire cage with an assortment of more mundane freight items. The gate was padlocked. Chrístõ reached for his sonic screwdriver. “Relax,” he said. “I’m just going to deal with the lock.”

“One false move…” he was warned.

“Yeah, yeah,” he answered. “You know, I was shot at only the other day. And last week I had to tackle a homicidal clown. A couple of months ago I had to deal with a whole tribe of spear-wielding natives trying to sacrifice my girlfriend to a volcano god. You lot are practically routine.”

“Are you REALLY as confident as you make yourself sound?” the terrorist leader asked.

“Answer MY question first and I might tell you,” Chrístõ answered. The lock dropped off the gate and he opened it wide. He felt almost relieved when he actually touched the TARDIS and felt its familiar vibration beneath his fingertips. He reached once more into his pocket, again a projectile weapon was trained on him as he slowly drew out his keys. He opened the packing case and stepped inside. He turned and looked at the three men behind him. “Come on in,” he said with a wide grin.

He was at the console by the time they all tentatively stepped over the threshold. He closed the door behind them.

“What… how…”

“See what I mean about indecisive,” Chrístõ said. “By the way, there IS an energy field that jams up projectile weapons and prevents them from being fired inside the TARDIS. So put the guns down and relax.”

That was a lie. He had heard when he was home on Gallifrey that the later models were being fitted with such fields, but his one didn’t have one. Not yet, anyway. He was working on how to rig one up, but he’d need some components that didn’t come as standard on a Type 40.

He looked up from the controls to see the three men all lower their weapons. They had believed him. They believed he WAS as confident as he sounded, too. He owed that to Cam. He had taught him a lot about looking sure of himself in a room full of diplomats all far more experienced than he was. Inside he WAS scared of automatic guns that could turn him into a sieve in a few seconds. He WAS scared for Julia and for Cam and Kohb, and the terrified Delphian lady’s maid and all the other innocents in the carriage. He was even a little worried about the terrorists. He didn’t want them turned to sieves by the government stormtroopers.

But he didn’t show it.

“My name Thurlow Kenet,” the leader answered. “What is this place and what you are doing?”

“This is the TARDIS. It is a transcendentally relative time and space ship and I am making an adjustment to allow for dematerialisation through the steel sky. It has an anti-transmat field built in to prevent unauthorised travel. I have to override it.”

“You can travel THROUGH the sky at will?” One of Kenet’s men asked in astonishment. “But the Civil Guard prevent all such travel.”

“Yeah?” Chrístõ gave him a wide smile and flipped the viewscreen on. “So you’ve never seen your planet like this before?”

If he had wanted to, he could easily have disarmed and disabled all three men right there and then as they stared in stunned silence at their planet from orbit. They hadn’t even noticed that Chrístõ had hit the dematerialisation switch while he was talking.

The steel sky seen from above was even more remarkable than from below. It WAS an engineering achievement to be commended and admired in itself. But it had very clearly become a prison for the people of the eastern continent. And for a very long time, as far as he could see it had been a tool of definite and deliberate oppression.

He turned to the environmental console and typed rapidly before stepping back and inviting his guests to look at the schematic. He had to explain to them what they were looking at, but when they understood, they exclaimed loudly with anger and frustration for a long time. Again, he could easily have overpowered them while they were so distracted but he knew there was no point, now.

“If you really want to make a difference, you need to listen to me, now,” Chrístõ said once he had a chance of making himself heard without shouting.

“I don’t think your friend is coming back,” the Delphian woman said to Julia as the anxious time ticked away and their captors looked more and more agitated. “I think they’ve killed him. They’re going to kill us ALL.”

“Chrístõ isn’t dead,” Julia told her calmly. “He’ll be back, and when he is, we’ll all be safe and it will be sorted. There’s nothing to be afraid of.”

“They’re going to kill us all,” she said again.

“Stop it,” Julia told her. “You’re a grown woman. If I’m not scared, you shouldn’t be. Besides…”

Somebody screamed. The gunmen suddenly became even more agitated than before. Three of them ran down to the other end of the carriage and took up positions that were clearly defensive. When the hostages looked outside they realised why. The stormtroopers Chrístõ told them to expect were pouring into the freight yard. A thumping sound on the roof suggested that some kind of airborne assault was coming as well. The gunmen were yelling at everyone to get down, but there was nowhere for them to get down. They were all jammed tight into the seats.

Then there was a sound that quickened the hearts of those who knew what

it was and confused those who didn’t. Two of the gunmen disappeared

as the space they were standing in was filled by the TARDIS in default

mode of a grey rectangular box with Chrístõ’s ![]() symbol

embossed on it. A moment later the door opened and Chrístõ

stepped out.

symbol

embossed on it. A moment later the door opened and Chrístõ

stepped out.

“Everyone, get in here, as quickly as you can,” he said. For a moment nobody moved. Then Julia stood, pulling the Delphian woman with her. Cam and Kohb followed. Then the rest began to rise from their seats. It was difficult. There was only a narrow aisle between the seats and the TARDIS door was only wide enough to admit two or three people at once.

There were still five or six people still struggling to reach safety when the smoke bomb smashed through the window. Chrístõ folded time as he sprang forward and grabbed it in mid air and threw it back out of the window.

“Move, now,” he shouted urgently and the last of the hostages and one of the gunmen ran into the TARDIS. He was right behind them, slamming the door shut as another smoke bomb flew through the broken window and filled the empty carriage. When the stormtroopers in their gas masks poured in they found nothing but a displacement of air wafting their smoke away.

In his office in the parliament building, in the middle of the administrative capital of Utepi Ionn, Grand Marshall Braigr Rho was an angry and a worried man. He was angry first because the train carrying the delegates to the lucrative trade conference had been hijacked, then because his stormtroopers had failed to either retrieve the hostages OR kill any of the terrorists. He was worried because it was bound to affect the trade negotiations as well as bringing questions from the governments who had sent delegates.

It could even mean war, he thought. And war was very bad for profit.

He looked up in surprise. There seemed to be something wrong with the light in his office. It seemed brighter. The light was coming from the window. He stood up and looked outside. In the street below people were looking up in fear and excitement and wonder at the same time.

Rho looked up. He didn’t feel any wonder or excitement. He WAS fearful, but for a completely different reason to the people who poured into the street and those who struggled to get back inside, away from the unaccustomed sunlight that beamed down from the clear blue sky that widened as the steel shield that had blocked it out for so many centuries slowly folded back.

He was afraid because he knew the game was up.

He turned from the window and went to the door of his office. As he grasped

the brass doorknob he failed to notice a ![]() symbol on it. He failed to

notice, until it was too late, that the door didn’t lead into the

corridor outside his office.

symbol on it. He failed to

notice, until it was too late, that the door didn’t lead into the

corridor outside his office.

“Don’t panic,” Chrístõ said as Rho stared at him and at the console room. “Nobody told you the venue for the conference had been changed. I’m here to escort you. Have you met Thurlow Kenet? He’s the leader of the newly formed Free Utepi Party. He’ll be standing against you in the election.”

“What election?” Rho demanded as he glared at Kenet sitting on the sofa.

“The one you’ll be holding in a few weeks time, once a full census can be called to establish the adult population eligible to vote. Apparently you haven’t actually had a free and fair election for about fifteen years – since you first came to power.”

“We’re not having one NOW,” Rho answered. “I don’t know what’s happening, but there will be repercussions. This is treason…”

“Right now this is a trade conference,” Chrístõ said. “The one you invited me to attend on behalf of my government.” He looked up from his console as the doors opened. “Exactly as I planned. Right in the conference chamber.”

“Where is this?” Rho demanded as he stepped out and looked around him. It was certainly a conference room, with the delegates seated, waiting for their arrival. But it wasn’t the hall he had arranged in the Utepian capital.

“We decided,” Chrístõ explained. “After the complete failure of your security, that a neutral location would be preferred. My friend the Ambassador for Haoelstrom IV suggested that Platform One would be an excellent venue and they were happy to move the facility into orbit above Utepi Ionn. As you may or may not know, Platform One can provide, on request, full broadcasting facilities, and now that the steel barrier has been brought down, it can reach almost every household on the planet. There have already been several interesting historical programmes explaining how the Mantle was fully restored by the end of the first century of life under the steel sky, and it could have been dispensed with then, but government after government saw the political advantage of keeping the people in ignorance. Yours was far from the first. But you DID know. The secret was known to the government. That’s why space transport is so closely controlled. So that nobody would ever see the planet from orbit and realise there was nothing wrong with the atmosphere.”

Rho said nothing. Chrístõ sat down in his chair. Cam stood and smiled faintly.

“We have, as you may have gathered, already discussed a great many things here,” he said. “It’s what we do, after all. We’re diplomats. We talk. And we reached a few conclusions. The first one was that, as much as we disliked being taken hostage we actually dislike you and your totalitarian government more. But although the vote of censure was unanimous we don’t have the power to force you out of office. That’s for the people of Utepi Ionn to do for themselves.”

Rho looked at him contemptuously. He was sure the people of Utepi Ionn would be powerless as they ever were.

“HOWEVER,” Cam continued. “We do have the power to enrich or bankrupt you. And it is up to you which way we go. If free elections on the basis of universal adult suffrage are instigated, and the independent adjudicators we will be appointing are satisfied, then we will be happy to approve very beneficial trade agreements that will improve the lives of all Utepians. Or if we are not satisfied, we will impose sanctions that will cripple your regime. It’s up to you.”

“And if I choose to ignore your sanctions? I have an army at my command…”

“Actually, I’m afraid you don’t,” said the Ambassador for Delphia, whose hair and make up had been immaculately finished by her travelling maid and beautician. “I’ve just been passed a very interesting message. Apparently your army is just as upset as the rest of the people by the way they were deceived. There has been a mutiny.”

Rho looked distinctly worried now. Around him the delegates looked satisfied. They knew there was very little left to be done now except the fixing of some signatures to the paper copies of the trade agreement. They would be done in good time to enjoy the buffet luncheon provided by the Platform One staff.

Rho signed.

They enjoyed the buffet.

|

|

|