Julia sighed with relief as she spotted the friendly letters spelling out ‘Lyons Tea Rooms’ and the warm glow of lights inside indicating that it was open. They had passed four pubs that were noisily full. Garrick was prepared to see what it was like in such an establishment, but Julia wasn’t and Chrístõ had the casting vote.

“This looks nice,” she said, pushing open the door and breathing the fragrant smells of tea brewing and warm cakes. A neatly dressed waitress showed them to a table and took their order for a ‘deluxe’ afternoon tea including sandwiches and cake assortment.

“’m glad to have some polite gentlemen in here this afternoon,” the waitress said. “I have been worried about getting a lot of those football supporters down from Lancashire or Yorkshire or wherever it is, making a ruckus.”

“No ruckus from us,” Garrick promised with an impish grin that was seen straight through by his tutors at the academy but worked a charm on women of all ages.

Chrístõ just pushed his football scarf deep into his coat pocket and looked as innocent as possible.

“You assured me that football hooliganism belonged in the 1970s and ‘80s,” Julia said accusingly. “You promised me a match in 1938 would be sedate.”

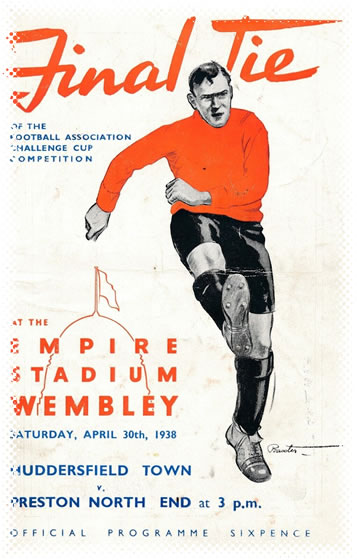

“The word I used was respectable,” Chrístõ answered. “And it was. I suppose some supporters are a bit loud. They’re excited. Preston North End won the FA Cup at last, after being soundly and humiliatingly beaten last year.”

“They made us wait THIS year,” Julia commented. “Twenty-nine minutes of extra time before the only goal. I honestly don’t know why anyone gets excited about football, at all.”

Chrístõ laughed, softly.

“Four hundred years later, girls still don’t get it.”

“You can’t honestly say you enjoyed that?” Julia countered. “Standing there all that time to see one miserable goal.”

“It was a GREAT goal. And, do you know, it was the very first cup final goal to be televised live by the BBC.”

He waited until the waitress brought a huge tray groaning with tea pot, cream and sugar as well as a four-tier stand piled with the food. Garrick started with a smoked salmon sandwich and a chocolate éclair on the same plate while Julia took a sandwich daintily and poured herself a cup of tea. Chrístõ took three sandwiches, salmon, cucumber and egg and cress and began to tell them about the television commentator.

“His name is Thomas Woodrooffe and he said at about one hundred and eighteen and a half minutes into the game -‘If there's a goal scored now, I'll eat my hat’. Seconds later, Preston got their penalty, George Mutch scored and Woodrooffe had to keep his promise.”

“He ate his hat? Really?” Garrick asked.

“A hat-shaped cake with marzipan topping, anyway.”

Julia and Garrick looked at each other and laughed.

“That’s cheating,” they both decided.

“Probably,” Chrístõ agreed. “Though I don’t think there are any rules, anywhere, about it.”

“The really annoying thing,” Julia pointed out, taking another sandwich. “Is that you KNEW all that already. You KNEW before we came here that your team was going to win – by one miserable goal at the end. You knew that joke. You know the other joke, too, that will be in the Preston newspaper tomorrow – about winning by ‘this Mutch’. You’ve got a copy of the cartoon framed in your study.”

“And….” Chrístõ teased her.

“And I have never been so bored in my life. WHY am I here? I don’t mind you taking Garrick on these weekend trips away from the Prydonian Academy, but what am I here for?”

“Later this evening we’re going to see a preview performance of Cole Porter and Kenneth Leslie-Smith’s new musical The Sun Never Sets, at the Theatre Royal Drury Lane. Tomorrow afternoon there is jazz in Regent’s Park, both opportunities to wear the fashions of this time. And since they suit you so well, on Monday you can enjoy a shopping morning in Oxford Street.”

Julia was mollified. Garrick was less than enchanted by the prospect of visiting ladies fashion houses.

“We’ll find something else to do,” Chrístõ assured his brother. I’m not sure what, since museums and galleries close on Mondays. But I’ll think of something.”

His thoughts, whether about Monday morning amusements in London or anything else were interrupted by a man who walked into the tea rooms, sat down at a window table and began crying. Everyone in the premises looked at him with various levels of curiosity, sympathy or disgust.

“He’ll be drunk, no doubt,” said the exasperated waitress, but Chrístõ stood and headed her off.

“I don’t think it is drink,” he said to her gently. “Let me talk to him. It’ll be all right.”

The waitress looked at him. He didn’t seem to be a policeman or a doctor. But something about his face seemed trustworthy in that way. She nodded and went to serve another customer while Chrístõ sat opposite the crying man.

“Hey… what’s the matter?” he asked. “Surely, it can’t be so very bad?”

“Everything is bad,” the man answered between sobs into a large handkerchief that he pulled from his pocket. “Everything is hopeless. I feel… I feel as if I could never be happy again.”

“But….” Chrístõ glanced at a scarf spilling from the pocket from where the handkerchief had come. “Everything is great. Your team just won the cup.”

Even for a Huddersfield supporter this much grief would be over the top. But why would somebody with a Preston scarf be crying? Granted, the initial euphoria could easily die down once a man was beyond the noise and crowds coming out of the stadium, but usually not that fast.

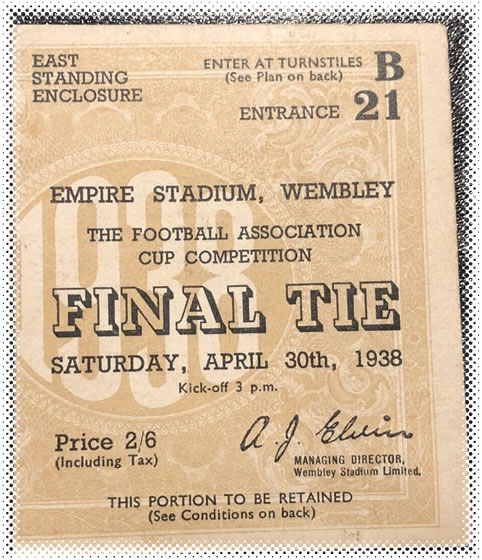

“The game….” The man pulled a ticket from a different pocket. It was intact. The stub had not been removed on entering through the turnstile. “I didn’t even get there. I went for a walk in the park this morning, and I can't remember anything else after that. I didn’t take a drink. I’m from Preston. I’m a pledger.”

That might have seemed an odd comment. Preston had as many pubs as any town. But it was also the place where the Temperance Movement was founded. Pledging to total abstinence from alcohol ran in families there.

“Maybe he NEEDS a drink,” said a man passing out the door who had overheard, but Chrístõ didn’t think that would help.

“What park do you mean?” he asked the man.

“Over that way….” He waved vaguely towards the wall. “It looked a nice spot to walk and sit and eat my lunch. I bought a meat pie. There was a young woman… in a strange sort of dress. I can’t remember anything else.”

Chrístõ was trying to think what else he could say to the man when he suddenly lunged for a butter knife. He was pointing it at his wrist when Chrístõ snatched it from him.

“Do you want to go to jail for attempted suicide?” he said. “Settle down.”

An unfortunate result of the man’s troubles was that a lot of other customers had left sooner than they might. But that meant there were only Julia and Garrick still sitting and the waitress talking to them – possibly because Julia had deliberately distracted her attention at this tense moment.

Chrístõ took out his sonic screwdriver and moved the blue light rhythmically to slightly hypnotise the befuddled man. Then he gently pressed his hands on his temples and slowly, carefully, entered his unresisting mind. He read the football fan’s most recent thoughts carefully, taking note of the ‘young woman in a strange dress’ in the park – before it all went very fuzzy and confused.

Then, he replaced the fuzziness with some very clear memories of the football match he had missed, including the excitement of that penalty. It was, he thought, the least he could do.

Chrístõ leaned back and picked up the match ticket from the table. He tore off the stub and put the larger piece back in he man’s pocket. Then he stood up and looked around at the waitress who was looking at him again.

“Please get another pot of tea for my wife and brother. I’m just going to walk to the tube station with Mr Edwards. He’s all right, now. Just a bit too much sun. But I’ll be happier once he’s on his way.”

The walk did Mr Edwards good. He talked brightly about the game. At Wembley Park tube station there were dozens of men in scarves of both teams waiting to get back on the underground to Baker Street and from there to Euston station and the special trains back to their respective towns in the north of England. He easily found cheerful company and Chrístõ felt it was safe to leave him.

On his way back to Wembley High Road and the Lyons Tea Shop, he had to step around a crowd watching two cursing and struggling men who were being put into a police van. They had been fighting in the street.

“Fifth lot this afternoon,” he heard a constable say.

“Really?” Chrístõ said, stopping and engaging the policeman in conversation. “That is unusual, isn’t it?”

“I’ll say. We had extra men on duty for the football. But that lot were no trouble. Noisy and excitable, but no trouble. Not even the losers. The troublemakers have all been local. These two say they were just in the park for a few hours. And there’s no sign they’ve taken drink, neither. It beats me.”

The park again, Chrístõ thought.

“What park is that?” he asked, hoping it would sound casual.

“That would be King Edward VII Park, just up the road. Lovely place to walk with your lady-friend.”

It was, Christo noted, nearly seven o’clock. Sunset would be about a quarter to nine. Not a lot of time for a walk, let alone an investigation. Unless….

The TARDIS was parked next to Wembley Park station, the place where he had left Mr Edwards - a five minute walk after he had paid for the tea and handsomely tipped the waitress who had put up with so much.

Then he carefully calibrated a short hop in both time and space. It was never a good idea to be in two places at once, but when the TARDIS materialised on the edge of the park, disguised as a Brent council shed, at three o’clock in the afternoon, he, Julia and Garrick were safely inside the Empire Stadium, commonly known as Wembley. There was no likelihood of meeting themselves.

“It’s a nice park,” Julia commented as they walked among fragrant flower beds.

“Dedicated in 1913 to the late king, replacing Wembley Park which was going to be ripped up for the new stadium,” Chrístõ said, quoting the TARDIS database.

“Thoughtful of them,” Julia noted.

“Victorians were big on providing green spaces in their cities. The Edwardians carried on the tradition. A bit patronising, really. It’s meant for poor people to have free access to leisure.”

“It is very nice. But what’s happening over there?”

“Possibly the thing making people act against their nature,” Chrístõ answered. “Let’s get closer.”

They moved towards the grey and red marquee set on a slight rise near what must have been the middle of the park. A small crowd were taking an interest, as crowds generally do, but the lack of any obvious entertainment or food vendors made it difficult to keep the interest going and the crowd came and went. There weren’t very many people interested in the young women with long hair loose down their backs and half veils covering their eyes, wearing dresses reminiscent of those worn by Roman and Greek goddesses in surviving statuary. Despite this, they persisted in going among the onlookers looking for people to invite into the marquee and were moderately successful.

“They’re only targeting single men,” Garrick observed. “Not couples and not women.”

Christo was impressed by his observational skills.

“Yes. You two stay here. I’m going to get a bit closer.”

“No!” Julia objected. “You don’t know what’s going on in there.”

“That’s why I need to get in,” Chrístõ answered logically – forgetting that logic had never worked on a wife in the whole history of marriage as he knew it.

“Let me go,” Garrick volunteered.

“Absolutely no chance. Your mother is more frightening than those women. If you get hurt…”

“One day, you will have to stop worrying about what my mother will say.”

“I do, frequently,” Chrístõ answered. “Then I worry about what our father will say to us both.”

“Being in loco parentis for Garrick is making you cautious,” Julia observed. “Which is fine by me. I don’t want you getting into danger. You’re meant to be settling into a nice quiet job in the Panopticon Tower.”

“Chrístõ said nothing. Julia didn’t know that his job in the civil service department high in the tower overlooking the Capitol was a front for working with Paracell Hext, at a very different Tower, where he was training Celestial Intervention Agency recruits. Everyone would go ballistic if it was known. Julia wanted him to live quietly. Valena would never trust him with Garrick’s welfare again. His father was sticking by a promise made to his mother, long ago, not to let him join the Celestial Intervention Agency.

Technically, he WASN’T a member of the Agency. But it was only a matter of time before he went on an offworld mission with them.

“If something unnatural to this world is going on, then I have to find out what it is, and if necessary, stop it,” Chrístõ insisted. “I can't turn away.”

Julia gave him a look that said ‘of course, you can. It’s none of your business. We came to go to a football match.”

Which packed a lot into a ‘look’. She may have been taking lessons from Valena. But he had made his mind up. He left his wife and brother sitting on a park bench with a high privet hedge behind it, well away from the activity, and mingled himself with the sparse crowd.

“What is it all about, then?” Julia wondered aloud. She had a book with her – a hardback first edition of Cold Comfort Farm which was safely contemporaneous and not by F. Scott Fitzgerald or George Orwell, two popular authors of the time that she disliked. She wasn’t reading much. She looked as if she was, but she was watching Garrick who was clearly using telepathy to study the people gathering around the marquee.

“They say it’s a temple to the goddess, Isis,” he said. “They are inviting people to come and worship and receive enlightenment. A lot of people are refusing because its ‘heathen and ungodly’. But Isis IS a goddess, so it can’t be.”

“Most English people at this time are either Roman Catholic or Church of England,” Julia said. “They would think that. Is it the Egyptian Isis or the Roman one adopted from the Egyptians? Roman makes a bit more sense. Isis would have had followers in Londinium under Roman occupation. Except Londinium didn’t include Wembley. It was much smaller. Chrístõ took me to a Roman market, once. The whole city was no bigger than an English country town.”

“They’re taling about reviving the worship of the Roman goddess,” Garrick confirmed, aware that Julia was talking about historical London to avoid thinking of what trouble Chrístõ could get into. “But it is all nonsense. The girls are telling men that worshipping Isis will bring them prosperity, health and long life through her blessings. I don’t think that’s what Isis was about.”

“Minerva was the Roman goddess of prosperity, I’m quite sure,” Julia said. “Not sure about long life. But this is a time, before the National Health Service, when money could buy better chances of long life. It goes together in a way.”

“Maybe,” Garrick said. But he was picking up the thoughts of some of the people coming out of the marquee and they didn’t seem as if a goddess had blessed them with anything other than the mother of all headaches. He felt one of them utterly depressed and crying like the man in the tea shop, while two others began arguing about a sixpence – whatever that was.

“I don’t think what goes on in there has anything to do with blessings of a goddess,” he said. “And I’d better make sure Chrístõ is all right.”

Julia didn’t argue. She privately thought Valena was too protective of Garrick and he was just as brave and resourceful as his older half-brother, and if they had to dive into any trouble that came their way, then the two of them backing each other up would be better all round.

“Hello, would you be interested in becoming a Sister of Isis?” Julia looked up from her pretend reading to see one of the ‘Sisters of Isis’ women standing in front of her.

“I’m too short to get away with robes like that,” she answered coolly. “I’d trip over the hem.”

Garrick was wrong. They weren’t just picking single men. There just weren’t very many single women about. This was still a time when walking in a park was for couples. Even older ladies went about in pairs with other older ladies. Besides, she was sure single women could get pestered just as much in this time as any other. She was just about the only lone woman around.

“I’m sure you will be just fine,” the Sister insisted.

“I'm sure I wouldn’t,” Julia answered, but an idea had occurred to her. She stood quickly and hit the ‘Sister’ on the side of her head with Cold Comfort Farm. She fell, stunned, and her veil slipped off. Julia noticed the size – too big, shape – too round, and colour – bright violet, that were definitely not Human traits. She didn’t need to feel guilty about assaulting an alien woman.

While nobody was looking, she pulled the alien Sister behind that conveniently tall privet hedge and stripped her of her gown. Beneath it she was wearing a kind of figure-hugging all-in-one bodysuit of fabric that was just possibly in the wildest dreams of contemporaneous science fiction writers. She quickly took off her own blouse and skirt and put on the gown over her petticoat. It WAS too long, but she had been given etiquette lessons not only from Valena, but also Queen Cirena of Adano-Ambrado and she could walk backward in a long formal gown in presence of royalty. Forward was no problem. Her hair fell from the demure neck roll she wore it in and the veil hid her face.

“You have a lie down and a nice read if you like,” Julia said to the unconscious alien woman, dropping Cold Comfort Farm beside her. She emerged from behind the privet and headed to the marquee.

Inside there was an arrangement something like a tented church meeting, except that the long box covered with scarlet satin cloth that served as an altar was set in the middle rather than one end. There were, of course, no crosses or other Christian symbols on it, but ‘altar’ was the word that came to Julia’s mind. She tried NOT to think of the prefix ‘sacrificial’ but it came disturbingly all the same.

A congregation of men were standing all around the perimeter, nearest to the tent walls. Most looked lower or middle class in good weekend suits. A few were clearly upper class in better suits and ostentatious walking canes and straw boaters – the sort of men who would be called Bertie or Raphe or Chas, at least in the literature of the time.

Whatever class they were, all the men seemed totally mesmerised – all except Chrístõ and Garrick. They stood on almost opposite sides of the tent and were possibly pretending not to have noticed each other. They were definitely not fixing glassy gazes on the altar and the dozen or so women in Roman gowns and veils who moved in a circle around it, chanting in what Julia, having travelled in the TARDIS for years, knew to be Latin but heard in English.

“Nos te vitae… Nos te vitae… We Bring You Life… We Bring You Life.”

Julia was fairly sure the life WASN’T being brought to the men who had been enticed in with promises of long life and health. They sagged slowly, even those with canes and boaters who had been taught to stand properly. All now seemed utterly enervated.

The altar glowed from within the satin cloth, and Julia stifled a gasp as she made out a shape inside what must have been a translucent container about the size of a coffin.

The word ‘coffin’ came into her mind because the shape inside was that of a man. The chant about bringing life put her in mind of the ambitions of Doctor Frankenstein. But his method was loosely scientific. This was more like a kind of voodoo magic, drawing energy, lifeforce, from the men lured into the marquee. Not enough to kill, perhaps, but enough to exhaust, to leave them with hormones like serotonin and others Julia couldn’t name offhand drained so that they became morose and suicidal like Mr Edwards in the tea room or violent like the men the police had been dealing with all afternoon. Perhaps there were other mood effects that didn’t cause such social interruption but would be noticed later by wives or mothers. Perhaps there would be long term medical effects like anaemia of the blood or osteoporosis from having certain nutrients drained.

In any case, it needed to be stopped. Julia wondered what she could do to help that come about.

The chanting seemed to be important, she thought. If she could help to disrupt that….

She slipped into the circle and began her own chant.

“Acta non verba… Acta non verba... Acta non verba....” Of the half a dozen Latin phrases she knew, which included ‘Et tu, Brute’, ‘In vino veritas’ and ‘Veni, vidi, vici’ the last of which she had forbidden Chrístõ to use in the wake of that tiresome one-nil ‘victory’ this afternoon, ‘Actions, not words’ seemed the most appropriate. Although, she thought, it was by using words to disrupt the chant that she hoped her actions would be effective.

And it DID seem to be working a little bit. The two women nearest to her were stumbling with their chant. One of them actually did start saying ‘verba’ instead of ‘vitae’. The other forgot her words altogether for several repetitions.

Latin was probably not their first language, and the chant was one they had simply memorised. In all likelihood the actual words weren’t important. It was the uniformity of the chant that produced the power.

Well, maybe. She would have to ask Chrístõ later if that made any sense at all. Anyway, she WAS causing a ripple effect around the group of women. Several of them were now chanting ‘Nos te Verba’ which meant something like ‘let’s talk’. Others were now saying ‘Actus nos vitae’ which Julia heard as ‘the deeds of our life’, which only accidentally made sense. The rhythm of the chant was destroyed, anyway, and the women were stumbling in their procession around the altar, too.

She threw ‘Vini, Vidi Vici’ in next, and the one she had used earlier without a second thought – ‘in loco parentis’. Both began to circulate with even more chaotic results.

Julia was sure the light inside the altar was changing, too, getting dimmer, then brighter all the time. But she wasn’t sure if that was her doing or Chrístõ and Garrick who had raised their hands to their temples and looked as if they were concentrating on something disturbingly telepathic.

Then the women screamed in one voice and collapsed to the floor. There was a deeper, guttural cry from within the altar and a thrashing from the shape within, followed by stillness.

“Everybody get out of here,” Chrístõ called out to the men suddenly released from the mesmer that had held them. They may have had no idea what was going on, but they knew that it was something from which they ought to get a long way. Quite quickly the marquee was evacuated. Only then did Chrístõ and Garrick move towards the altar.

Julia moved forwards, too, but Garrick stopped her.

“You probably don’t want to look at whatever’s in there,” he said.

Julia would have protested, but she saw Chrístõ’s expression when he drew back the cloth. He immediately pulled his sonic screwdriver from his pocket and with a quick adjustment aimed it inside at the shape. There was a red glow and the shape disappeared.

“Nobody needs to see that,” he said without explanation. He turned and brought his brother and wife out of the marquee. He saw that there was a St. John’s ambulance there, the medics busily treating people for ‘exhaustion’. He spoke to one of them.

“There are some young women in there. They were dancing in the heat of the canvas without proper ventilation and fainted. Perhaps you could have a look at them. But I think they’ll be all right with the door open.”

Julia wondered if the violet eyes would puzzle the medics, but Chrístõ told her not to worry about it.

“Some of them WERE Human,” he said. “There are only three actual aliens. They were using the women to power the chant, and the men to extract what they needed.”

“Why?” Julia asked. They had reached the bench. She went behind the privet and recovered her clothes and her copy of Cold Comfort Farm. The alien woman was still out cold. Chrístõ thought it was more about a psychic link with her sisters than being smacked by literature.

“Believe it or not,” he said as they headed back to the TARDIS and a rest before heading off to Drury Lane. “They wanted to make a man – in the sense meant in the Rocky Horror song – from scratch inside a tank of nutrients. They used a form of mind power to extract lifeforce from men for their prototype. That’s why they didn’t use women for that.”

“Why… and I know I might regret asking this…” Julia began. “WHY did they need to MAKE a man?”

“Because the men were wiped out by a very specific plague. They need a man to procreate.”

“One between them?” Julia asked. “I don’t know any three women who would agree about THAT.”

Chrístõ laughed with her. At least she wasn’t asking any more questions about the birthing tank. He hoped she would be happy to have his children in a year or two. The memory of a man-sized embryo still not fully formed, the beating heart and lungs visible on the outside and worse, might not make her feel so good about the prospect. Better she imagined a Frankenstein creation of some sort.

|

|

|