Julia walked at Chrístõ’s side along the long cloister with the thousands upon thousands of names inscribed. He was almost oblivious to her. He seemed to be reading all of the names. His eyes dilated rapidly and his lips were silently moving. She considered several possible openings to a conversation, but she couldn’t quite get the words out. Even when she reached out and touched his hand he seemed unaware of her presence.

They reached the end of the cloister and went down a flight of steps to the long memorial courtyard where they walked by the reflecting pool. Chrístõ blinked in the bright sunshine and looked up at the blue sky, then he half turned and seemed to see her beside him at last. He gripped her hand and smiled at her. She felt a little relieved to see him ‘back’ with her.

“I’m sorry,” he told her. “I know this isn’t terribly interesting to you. But I really wanted to see it. It is a magnificent war memorial.”

“It is,” Julia agreed. “I never really thought of you as somebody who was interested in this sort of thing, though.”

“I never was before,” he admitted. “Until I fought in a war.”

“Oh!” Julia felt guilty. She thought of wars as things that happened long ago, that were in the history books she read at school. War memorials like this one, the Australian National War Memorial in the city of Canberra, were reminders of mankind’s past follies.

It was strange to think of Chrístõ as a war veteran. That, again, was a term that she associated with old men. Chrístõ WAS, of course, much older than the oldest Human she knew. But for his species he was a young man. And standing there, in the sunshine, wearing sunglasses and with the top two buttons of his cotton shirt unfastened, he looked like somebody with his life ahead of him and without a single care. It was easy to forget that he was scarred inside by horrors he hadn’t even been able to tell her about.

“I live my life outside of time,” he said in a quiet voice. “In this place, this time, the war I fought hasn’t happened… won’t happen for centuries. But for me, in my personal lifetime, it’s just about a year since the Liberation of the Capitol. It’s still a raw wound in my mind. When I think of all the people who died…” He paused. Julia noticed him blinking rapidly. That was what he did when he was trying not to cry. “We don’t have a war memorial. I don’t think we’ve even got a complete list of names. Even if we listed the Gallifreyans who died, we’d probably forget how many of our allies gave their lives for our freedom.”

“This memorial was commissioned after the first World War of the twentieth century,” Julia pointed out. “But it wasn’t finished until 1941, in the middle of the second war. Maybe you just have to be patient. Your people might be thinking about building something like this, but they haven’t got started yet.”

“No.” He shook his head. “I think they just want to forget it happened. They’ve almost rebuilt the Capitol. Everything is getting back to normal. Nobody even talks about it now except me and Paracell Hext and the mother of Malika Dúccesci – and I’m not even sure who she talks about it to. She doesn’t leave her house and she doesn’t receive visitors.”

“That woman needs help. I hope she gets it. But you and Hext have each other… and he has Savang now and you will always have me. And you can talk to me about anything you want. Even the war. You’ve never really told me what it was like. All I really know about it is that you were gone for weeks and I was worried about you. It was like being one of the women left behind when those men went to war… the ones whose names are in that memorial. Only I was lucky. You came through it. And I was glad to forget about it all once I had you back. I never really considered that you couldn’t just forget. And I’m sorry about that.”

“There’s nothing for you to be sorry about,” he assured her. “We should forget to hurt every time we think of what happened. But we shouldn’t forget what it cost. We should have a memorial like this. We should inscribe the names of those who died. We should remember them with proper honour.”

“Then, when you’re home again, you should talk to the people who can make it happen. You’re the heir to one of the Twelve Ancient Houses. You should be able to make them listen.”

He smiled at her. She was right. She so very often was. Where he saw complications, she saw straight through to the simple core of things.

“What would I do without you?” he asked as he hugged her.

“Marry Romana and join the Gallifreyan Civil Service,” she answered. He laughed softly and bent to kiss her.

“I’m not sure we’re meant to do this in a National War Memorial,” she told him as he leaned back from the kiss but continued to hold her around the shoulders. There were a few disapproving glances from other visitors. They didn’t know that Chrístõ was a war veteran who cared very deeply about the dignity of this place. They just saw a couple of teenagers acting inappropriately. She pulled away from his embrace and they walked on past the reflecting pool to the Hall of Memory. The disapproving glances melted away now that they were no longer doing anything of interest.

All but one. Just before they stepped into the cool quiet of the memorial hall, Julia noticed a man standing by the pool who was staring right at them both intently. There was something about the way he was looking at her that made her uncomfortable. She couldn’t have explained why. She turned to Chrístõ who was glancing up at the inscription over the entrance to the hall. Then she looked back again. The man was gone. That was odd, but if he was gone it wasn’t worth mentioning it. She stepped into the Hall of Memory and admired the beautiful domed ceiling, the stained glass windows dedicated to the armed services of Australia and the simple but poignant Tomb of the Unknown Australian Soldier where by tradition visitors left poppies. She watched as Chrístõ put a small white flower down instead. She knew enough of his world and its traditions to know that it was called a Memento Mori Lily and its significance was much the same as the poppies were to humans.

That gesture of solidarity with the fallen of Human war seemed to set to rest those ghosts that had haunted him. When they stepped back out into the sunshine he smiled widely at her.

“That’s what I came here to do,” he told her. “Now, let’s do what you want to do for the rest of the day.”

“I think I’d like to have lunch before we do anything else,” Julia answered. “Maybe we could go down by the lake with a picnic. And then afterwards we could go and see the parliament buildings for the afternoon.”

“Sounds good to me,” Chrístõ answered her. He smiled and took her hand and they walked together in the warm sunshine of a late spring in the Australian Capital Territory – which was considerably hotter than it was even in mid-summer on Beta Delta Three. Chrístõ seemed happier now. The war memorial had stirred some emotions in his two Gallifreyan hearts. But now he was able to relax again as they walked down to the place where he had left the TARDIS - disguised as a tree in the green area around the memorial complex. It was almost indistinguishable from the other trees, except for the Theta Sigma carved into it. Chrístõ pressed his hand against the symbols and a door resolved itself. They stepped inside. Chrístõ made only the very slightest adjustment to their spatial position, moving the TARDIS a mere two kilometres to a place called Commonwealth Park where the tree disguise was again appropriate. This time the TARDIS was a pale green fronded willow tree by the edge of Lake Burley Griffin. Chrístõ brought the picnic basket and they sat in the TARDIS tree’s shade to eat their lunch.

“What do you think of the ‘real’ Canberra then?” Chrístõ asked. “Does it measure up to New Canberra.”

Julia looked around at the delightful spot where they were sitting and sighed happily.

“It’s much better here, I think. New Canberra was based on this city. It has the same sort of layout, all very neat and organised. But it’s not as pretty. The materials they shipped out to build the city with were much more functional. They had to be, of course. Because it was all so expensive and such a long journey. Even Earth Park isn’t quite as nice as this is. The lake is man made and nowhere near as good. And the weather is better, here. I know it’s a bit traitorous to say so, but the original Canberra is nicer. Even so, New Canberra is home to me. I love it for that.”

“This is the other side of the planet to Cambridge,” Chrístõ noted. “Where you were born. But doesn’t Earth itself feel like home, all the same?”

“Not really,” Julia answered after giving it a little thought. “Not now. I’ve been away from it since I was just turned eight. I’m sixteen and a half now. Between the ship, and travelling with you, then living on Beta Delta, I’ve only lived on Earth for half of my life. The rest I’ve belonged to the universe. I think of Earth as a special place – the homeworld. Everyone on Beta Delta does. We’re all colonists, after all. But it’s not home any more. It’s the same for everyone. A lot of my friends were born on Earth, but they only just remember it from when they were little. When they all grow up, their children will just know stories about Earth. They’ll be real Beta Deltans, not settlers and colonists.” She looked around the park again and thought about the history of the country they were in. “The people who built this city would understand what I’ve just said. Their parents or grandparents were colonists who thought of another place as home. They built this park and their parliament house and libraries and museums as their way of saying that they were Australians, now.”

Chrístõ nodded. He thought she had expressed herself very well.

“Our children will be Gallifreyans,” he reminded her. “You’ll become a Gallifreyan, too.”

“Yes,” she said. “Neither Earth nor Beta Delta will be my home, then. I’ll have to get used to a new home. But that’s all right. That home will have you in it. So it will be easy to get used to it.”

Chrístõ smiled widely as she said that and reached to kiss her. She sighed happily and let him. She was sixteen, old enough to lie back in the grass under the shade of a tree and enjoy being kissed by a handsome young man who loved her. She looked at him as he drew back from the kiss. Even under an Australian sun he still had a pale complexion, but his eyes were a warm brown and they twinkled with joy as he embraced her. His lips were soft. His curling black hair framed his face - the face of the man she had known and trusted for a quarter of her life so far.

“I love you,” she told him out loud.

“I love you, my Julia,” Chrístõ answered, claiming another kiss from her. “Are you sure you want to see the parliament? We could just stay here in the park and do this all afternoon.”

“No,” she almost reluctantly replied. “We’d better do something else in a little while. It would be too easy to get comfortable here.” She sat up and looked around. Then she froze. She reached and touched the diamond brooch pinned to her blouse. “Chrístõ,” she said telepathically. “There’s a man over there, watching us. And I’m sure he was at the war memorial, too.”

Chrístõ didn’t say anything. And he didn’t turn his head. He put his hands either side of her face and closed his eyes. She felt his telepathic touch inside her head, an exciting feeling like quicksilver in the synapses of her brain. She knew he was looking through her eyes. He drew back after a minute or so, puzzled.

“I saw him for a moment. And then he was gone. Just like that. It’s odd.”

Now he did turn. He stood up and glanced around. There were a lot of trees in the park, and plenty of people, too. One individual could easily disappear.

“Stay there. Keep your brooch switched on. If you feel threatened, tell me.” He sprinted away, reaching the main path through the park. He looked up and down. He ran up a slight rise that gave him a much wider view. He could see Julia sitting alone. There didn’t seem to be anyone else near her. A couple with small children were heading down towards the lake itself and a boy was running with two small dogs at his heels. Nobody seemed to have any sinister intent.

It might have been a coincidence. Julia might have been mistaken. It might all have been perfectly innocent.

Or not.

After all, it wasn’t so long since he had foiled a kidnap attempt. He thought they would be safe on Earth in the early twenty-first century. Especially since Hext had the perpetrator of that particular crime well under lock and key. But it was possible that he had friends, loyal servants, who might have some half-baked idea of revenge in mind.

“Please, no!” he thought. “I just want a nice, peaceful holiday with Julia. I don’t want any intrigue, any danger. I want to enjoy visiting a nice city with lots of cultural things to see and do. And that’s all. Give me just that one bit of peace!”

He looked around one more time. Everything seemed perfectly normal. Nothing was disturbing his peace except his own paranoia. He took a deep breath and calmed his fears and then walked back to Julia. He smiled warmly and kissed her again one more time before they packed away the picnic basket. He looked around carefully before they went back into the TARDIS.

“Do you think it will disguise itself as a tree again,” Julia asked. “There are some around the parliament buildings.”

“It very well might,” Chrístõ answered. “I’m not sure whether there’s something wrong with the chameleon circuit or it’s just having a joke with us.”

“It’s just being consistent,” Julia assured him. “Besides, it gets fed up of being transporters and airlocks and linen cupboards.”

Chrístõ laughed. “I sometimes think I should keep a list of all the disguises the TARDIS chooses. Just to see how creative it can be. Maybe you should take notes for me.”

Julia laughed with him. Any vestige of worry about strangers watching them vanished in the laughter. A few minutes later the TARDIS materialised in the public car park of the Australian Parliament disguised, not as a tree this time, but as a rather nice car in an unusual deep plum colour.

“Very good,” Chrístõ said, patting the bonnet. “It’s an Australian made model – a Holden Commodore. Very incongruous. Full marks. Just make sure you’ve got your parking permit displayed. Remember that time in London when you nearly got put in the crusher!”

Julia was shaking with laughter as he took her arm and they headed towards the main entrance to the spectacular looking modern parliament building, half concealed under a grassy hill where the flag of Australia was proudly flying. The architecture on its own was fascinating. They joined a guided tour inside and listened to the history of democracy in Australia, from the establishment of the Capital Territory and the city they were in, to the completion of the modern parliament building. Both of them were fascinated, she because she was studying political history at school and he because democracy as practiced on planet Earth always had an attraction for him. The Australian model seemed to him a particularly good example of what he thought was one of the best ways of legislating for a people with wide-reaching needs.

“I had never even heard of a bi-cameral political system before I came to Earth,” he told Julia telepathically as they stood in the public gallery overlooking the Australian Senate chamber and heard the tour guide explain that the colour schemes in the two chambers reflected those in the British Houses of Parliament. But the green in the House of Representatives was a muted grey-green of eucalyptus leaves and the red of the Senate was red ochre, the colour of the soil in the outback plains of Australia.

“The High Council seats in the Panopticon are copper coloured,” Chrístõ added. “I don’t think that represents anything. It is the colour of our moon in one of its aspects, but I think that’s a coincidence. We don’t really build symbolism into our public places. We have enough of it in the rituals we conduct within them. I think we could learn from a political system like this one, though. Gallifrey is far from a democratic world.”

And yet, Julia thought. He never thought twice about throwing himself into the war to defend that flawed world of his, to restore that form of government he didn’t even approve of. She realised as the thought was forming that he was already reading her mind. He smiled wryly.

“Better a flawed meritocracy than a conquering dictatorship,” he answered her. “Perhaps change will come to Gallfrey one day. And maybe it will be in my lifetime. But let it come in due time, not through force of arms.”

He reached to take her hand as the tour moved on and noticed that she was looking the other way. He followed her gaze and stiffened as he saw that same man she had drawn his attention to in the park. That really couldn’t be passed off as a coincidence.

For a brief moment his eyes met the stranger’s eyes across the gallery. Then in an eyeblink he was gone. Chrístõ was startled. Nobody could move that fast.

“He wasn’t a part of the tour group,” Julia said to him. “There were only eight people including us and there are still eight here. He just turned up.”

“He shouldn’t have. This area isn’t open to the public unless they’re in an escorted group.”

“This is creepy,” Julia said. “I don’t like it.”

“Neither do I,” Chrístõ told her. “But stick beside me for the rest of the tour, and then I’ll take you somewhere he can’t possibly follow.”

It spoilt the rest of the tour for them both. They were glad when it was over. Chrístõ took a very indirect route back to the car park, lingering in the souvenir shop and buying some interesting trinkets including a snowglobe with a model of the old Parliament House in it. They reached the plum coloured car without being observed and a few minutes later it vanished from the car park without anyone noticing its absence.

This time the TARDIS materialised as a door marked ‘staff only’ on what Julia at first took to be the deck of a space ship of some sort until Chrístõ led her out onto the balcony.

“The Black Mountain tower,” he said. “Same idea as the old Post Office Tower in London, but perched on the top of a hill overlooking the city of Canberra. And if the mysterious stranger turns up here, I’m going to check the TARDIS for homing devices.”

He made a joke about it, but it was starting to become the only conclusion. They had used no public transport, no roads by which they could be followed. They had gone from the war memorial to the park and then to the parliament by TARDIS each time. It was, he had admitted to himself, a frivolous use of the TARDIS, but Canberra in spring was a much hotter climate than Julia was accustomed to and he wanted her to enjoy the sights, not wither from heat exhaustion travelling between them. But it should have meant that nobody could follow them. It made it all the more sinister.

“This is beautiful,” Julia said, leaning on the iron railings and looking out over the fantastic vista. The city, built around Lake Birley Griffin, was notable for its greenness. Even among the tallest skyscrapers on the horizon there were parklands and trees. But from this vantage point, they could see that it was something of an oasis. Beyond the suburbs of the city an arid, ochre coloured plain stretched as far as the distant mountains, broken occasionally by clumps of trees around smaller bodies of water.

“Have you got a coin for the telescope?” she asked. “I think I can see where we had our picnic lunch and the memorial and everything...”

“No need for a telescope when you’re with me,” Chrístõ answered her. He stood behind her, one arm around her shoulders. With the other, he pressed his hand against her forehead. Julia gasped as she felt his telepathic power affecting her eyesight. She blinked a couple of times as she tried to focus.

“Don’t force it,” he said. “Just look towards what you want to see and it will happen naturally.”

“I can see things close up, just like with a telescope. Yes, that’s where we were sitting when we had our picnic. There’s the jet fountain in the middle of the lake dedicated to Captain Cook.”

She excitedly pointed out several more distant landmarks that they had seen close to in the course of their visit. She could have gone on longer, but she started to wonder if Chrístõ could keep up the telepathic connection without wearing himself out.

“The telescope would have been less trouble for you,” she pointed out to him. He stayed where he was, holding her around the shoulders but she felt him breathe deeply.

“But not as intimate,” he admitted. “Don’t worry. It isn’t a very difficult thing to do. We used to do this for fun when I was at school. We would stand on top of the dormitory and see who could spot the furthest landmark using somebody else’s eyes to prove we weren’t lying.” He paused before mentioning that they were caught once and given detentions for being on the roof in the first place while receiving commendations for their well-developed telepathic skills.

“You’ve never had trouble with heights, then?” Julia said to him, laughing joyfully and enjoying standing there with his arms around her.

“None at all,” he answered. “High places tend to be quiet, peaceful. This is perfect. Just the two of us here, like this.”

“We should stand on tall buildings alone together more often.”

“We should do lots of things alone together,” Chrístõ said. “And we will. There’s a place I would like to take you, on Gallifrey. Halfway up Mount Lœng, there is a cave behind a waterfall, perfectly dry and warm, with the curtain of water falling past the entrance. When the Brothers on top of the mountain were teaching me meditation, I used to spend hours in there, alone, concentrating my mind. The Brothers said my mind was too full of activity, reaching too far and too fast to understand everything, to know all the wonders of the universe at once. I was told I had to find a point of existence where the cave, closed off from the outside by the waterfall was my entire universe, as if nothing else existed.”

“And did you?” Julia asked.

“A little too well,” he answered. “It was about five days before a group of the Brothers came down from their sanctuary to find me. And it took them two days to wake me from the self-induced trance. I’d gone so far into that contained universe they really worried whether they could get me back into the real one.”

“And what did it teach you in the end?”

“I’m not entirely sure,” he admitted. “I never quite understood why taking myself into a place where I was the centre of existence was a good thing. There are enough people in the universe who think it revolves around them. I don’t think I ought to be one of them. I think it was meant to teach me to slow down and be patient and to curb my over-reaching ambition. They may have slightly failed in that. It was always one of my faults. But… I think I could be very slow and very patient if I were to take the woman I love up there to that cave… just the two of us, some good food and wine and…”

He paused. Julia felt his arms tighten around her and heard him sigh softly.

“It sounds like a nice idea so far,” she told him.

“It is a nice idea. But it’s one you’re not ready for yet. I think it isn’t supposed to happen until we’re properly married. I’m pretty sure it will happen, though. It’s one of the gifts of a Time Lord, along with telescopic sight. We can see the future if we try very hard. And that’s a vision of the future I’ve had for a very long time.”

“Er… just how long?” Julia asked him.

“Since before I knew you,” he replied. “Long before I knew you. I first had that vision when I was with the Brothers, learning their mental disciplines. I told the Mentor about my vision. In… rather more detail than I’ve given you. He said it was precognitive. Then he said it was proof that my destiny was not to become one of them, devoting my life to contemplation. I was meant to belong to the universe and to experience its pain as well as its pleasure, its darkness and its light.”

“So… you saw a vision of us… together… married… before you even met me?”

“At the time, the woman who was with me was rather less well-defined. I think my destiny might have been in some state of flux then. It was only later, when Li read my timeline, that I knew that I was going to find love beyond my own solar system, and with another race than my own. And it wasn’t until I actually found you on that ship that the whole thing came fully together.” He pressed his face against her hair and closed his eyes. He felt the softness of it against his cheek and smelled the faint traces of the shampoo she used. In the precognitive vision he knew there was a different scent. On Gallifrey women tended to use natural herbal preparations in their hair, from plants picked in their own gardens. By the time he brought her to that mountain she would have taken up that same habit. It was all still in the future, yet. But he had little doubt that it would happen. The love between them was as strong as it could possibly get. Nothing could stand in the way of that future.

“Chrístõ…” Julia whispered in a tone that broke that prophetically romantic mood to pieces. “I think…”

He felt it, too. They weren’t alone on the viewing platform. He could feel the presence of somebody else telepathically. He berated himself for daydreaming so much that he didn’t notice it sooner. Now, he moved very slowly, very deliberately, turning his body fully around. He had no weapon, not even the sonic screwdriver. He had left it in the TARDIS when they went to the Parliament Buildings, because he didn’t want to bother having to hypnotise the security guards into believing it wasn’t something they should confiscate. But he got ready to fight, even though he couldn’t see anyone at all. He focussed his thoughts. There was somebody with a telepathic mind and some kind of perception filter very close.

He lunged forward and grasped at thin air. His hands connected with the shoulders of somebody about his own height and weight who shoved back irritably.

“Who the hell are you, and why are you following us?” Chrístõ demanded, throwing a punch that was expertly blocked. He was surprised when the stranger didn’t try to fight back but simply defended himself from his blows. “Who sent you… what’s this?” He snatched at the object around the stranger’s neck. It looked like an ordinary door key on a piece of string, but there was some makeshift micro technology soldered onto it that had a very strange resonance. “A home made perception filter? How did you…”

“Chrístõ! Somebody is coming,” Julia called out. He glanced around and saw two security guards heading for the glass doors to stop what appeared to be a fight on the viewing platform. The stranger grabbed his key back and with surprising strength pushed Chrístõ back to the railing. He grabbed Julia’s hand and Chrístõ’s and pressed them both against the key.

“Be quiet, both of you,” the stranger said. “We don’t want to be thrown out of the tower. Not if your TARDIS is near here. Just stay cool until they’ve gone.”

The guards stepped out onto the platform and split up to search for the people they thought were causing an affray. They came back together, puzzled, a few minutes later. One of them looked over the railing, perhaps expecting to see bodies at the foot of the tower, then they went back inside.

“Who are you?” Chrístõ said again, breaking away from the stranger’s hold, and the range of the perception filter. He pulled Julia away, too. “And how do you know I have a TARDIS…”

“If I didn’t, I do now. You just confirmed it. Not very bright for a Celestial Intervention Agency man.”

“You’re CIA? Hext sent you?”

“No,” the stranger replied. “I’m you. From your personal future. Don’t you recognise my psychic ident?”

“Don’t be ridiculous,” Chrístõ answered him. “How can you be me? You’re… you look the same age as I am. You can’t be a future incarnation… It’s a trick.”

“Why would I try to trick you? You know perfectly well that regeneration is a lottery. Age, body shape, just about anything can change. You don’t want to know how old I really am or how many of the lives you’ve still got before you are used up by the time I got this body. Just believe that I need your help right now. And if you want to carry on having a peaceful holiday here in this city, then it’s in your interests to help me make sure the city is still here tomorrow morning.”

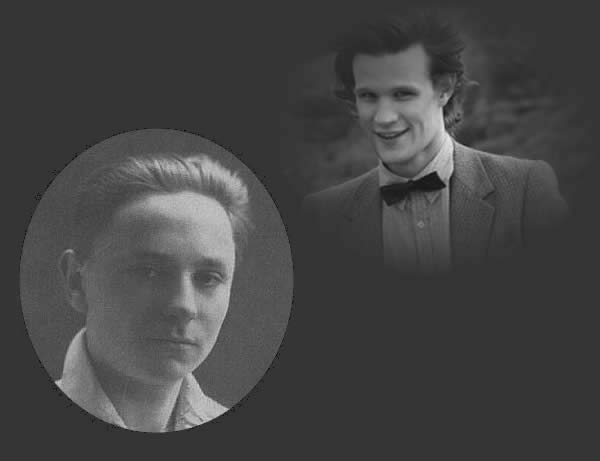

“You mean there’s a possibility it might not be?” Julia asked. The stranger who claimed to be Chrístõ in the future turned to look at her. He smiled in a way that made her gasp. He was tall and slim and had dark hair and brown eyes and a pale complexion. But his features were completely different and his clothes looked more suited to a man twenty years older who had spent his life in a university library. He wasn’t Chrístõ as she knew him.

All the same, there was something in his smile when he looked at her.

“There’s a very grave possibility, Julia,” he answered. “It’s good to see you, sweetheart, even though I have been trying very hard not to. I wanted to get him on his own so that you wouldn’t have to be involved. But he doesn’t seem to have left your side all day. Of course, it’s not that long since that nasty incident with the Creelans. I know I was feeling a bit over-protective…”

“It is you,” Julia said. “Chrístõ… my Chrístõ… I’ve seen other versions of you. There was a very old man with the same eyes. That was Chrístõ near the end of his first life. And another time I met a nice middle aged man who had question marks on his jumper. And there’s one who wears the same leather jacket as Chrístõ, but much older…”

“All me,” he admitted. “And all missing you like mad, Julia. I’m sorry I scared you. The perception filter failed a couple of times. You weren’t supposed to know I was there. Like I said, I’ve been trying to get him alone.”

“How did you follow us?” Chrístõ asked. “Is your TARDIS nearby?”

“No. That’s one of my problems.” The future version of Chrístõ who was known to friends and enemies alike as The Doctor looked more than a little embarrassed. “My TARDIS is… well… basically… the bad guys have it. I’ve… lost my TARDIS. It’s just a million to one piece of luck that you happened to be here. Otherwise I would be sunk and Canberra would be doomed. So… come on. Let’s go…”

“Go where?”

“To your TARDIS,” The Doctor answered. “Please, we really don’t have time to mess about now. They’re getting ready to take the city.”

“Who are…”

“I trust him, Chrístõ,” Julia said. “Come on. I wanted a quiet holiday, too. But if people are in danger, we have to do something.”

“I have to do something,” Chrístõ decided. “And he does. You don’t. Whatever we’re doing, and wherever we’re going, YOU stay in the TARDIS. Ok, come on.”

He turned and dashed away. Julia looked at the apparently older version of him and then the two of them followed him to the ‘staff only’ door. On the threshold The Doctor looked around in some surprise.

“I’d forgotten what it used to look like. It’s changed a lot.”

“You still have the same TARDIS?” Julia asked.

“Yes. That’s why this one let me…” He reached into his pocket and pulled out what looked like a chunky version of Chrístõ’s sonic screwdriver with something like a television remote control welded to it. He held it up proudly and seemed a little disappointed that his younger self wasn’t immediately impressed. “I couldn’t get back to my own TARDIS, but I was able to pick up the resonance from yours… I jury-rigged the sonic screwdriver to act as a short range transmat homing in on where you were.”

“Clever,” Julia commented.

“Dangerous,” Chrístõ remarked. “At worst you could have coated the exterior of the TARDIS with your insides. At best you must have got a blinding headache every time.”

“I did. That’s why I knew I had to take a chance and approach you the last time. If I’d let you leave the Tower I couldn’t have followed you again.”

“We were going to have dinner in the revolving restaurant,” Chrístõ told him. “So you wouldn’t have missed us. I’d still like to do that if we can. So how about telling me what this is all about.”

The Doctor approached the TARDIS console. He stopped in surprise as a shadow moved under it.

“Humphrey…” He smiled widely as the darkness creature hugged him around the legs. “He knows me. After all these years. Humphrey Boggart. Daft joke. But it fitted him so well.”

“You’d better save the reunion for later,” Chrístõ told him, not unsympathetically. “There are more than a quarter of a million people whose lives are at risk, according to you. Can you show me where the danger is coming from?”

“Take the TARDIS into a synchronised orbit over Canberra and then adjust the scanner to allow for a hydro-static cloaking device,” The Doctor told him. “You… know how to do that...?”

“Don’t be patronising,” Chrístõ responded as he did what his older self told him to do. “I haven’t LOST my TARDIS. How did you manage to do that anyway?”

“I just managed to sabotage the missile array of the cloaked ship you’re about to spot any minute. That delayed the attack and bought me some time to use the TARDIS to disrupt the warp-shunt engines and make it jump to the year five billion and fifty when the Sol System was dust. A long trip home from there for them.”

“Good plan,” Chrístõ said. “Warp shunt engines are no match for Time Lord technology. What went wrong?”

“I got caught. I had to run for it… straight into their transmat dock – one of them got creative and dumped me on the planet. It’s a good job you were here. I’d be stuck.”

“Don’t you just love billion to one chances,” Chrístõ commented dryly. “They’ll get you out of trouble nine times out of ten.”

Julia giggled at his improbable statistics then gasped as she saw the spaceship that appeared on the screen. She wasn’t really an expert on space ships. She had really only known two of them in her life, and one of them was the TARDIS. But the one that was hanging in low orbit over planet Earth – specifically over the Australian Capital Territory – didn’t look as if it had peaceful intentions. Something about its design screamed battleship.

“It’s Deten Cassian,” The Doctor explained. “You know of that race?”

“No,” Chrístõ answered. “I have a feeling I’m going to find out.”

“They’re a sort of air breathing two legged shark with hands that have opposable thumbs. Very bad-tempered, and they’ve been at war with the Deten Xassians for nearly as long as the Sontarans have been fighting the Rutans.”

“Before I was born, then,” Chrístõ noted. “But what does that have to do with Canberra?”

“Let’s sort them out, first,” The Doctor replied. “Then I’ll explain it to you over dinner in the Tower restaurant. My TARDIS is in the engine room. Can you materialise around it? We can use both engines to complete the process a bit faster this time.”

“Materialising around another TARDIS – especially when it’s the SAME TARDIS – is a very tricky manoeuvre,” Chrístõ said. “It’s like trying to eat your own head.”

“If you can’t do it…”

“I never said I couldn’t do it. Just grab hold of something. I can’t promise it won’t get bumpy. Julia… hold on tight, sweetheart.”

Julia grabbed a handhold. She was slightly surprised when The Doctor put his arm around her back and grabbed the same handhold as if he felt she needed extra protection. She glanced around at him and said nothing. He WAS Chrístõ in a future life. She knew she could trust him with her own life.

Chrístõ noted the gesture, too. He wasn’t sure how he felt about it. But he was too busy single-handedly completing a manoeuvre that took six students when Lord Azmael taught them to do this and warned them it was only to be done in an absolute emergency when there was absolutely no other alternative. He recalled the dark warnings of what could go wrong, from simultaneous implosion and explosion to ripping a hole in reality. He knew he ought to ask his older self to help him, but a stubborn streak in him made him want to do it on his own.

There was no implosion or explosion, and the fabric of reality was undamaged. There was an eerie noise like the usual materialisation sound played in reverse on an old gramophone, and a 1950s English police telephone box appeared in the middle of the console room. So did three guards who looked very much like walking, air breathing sharks. The hands with the opposable thumbs closed on the triggers of three deadly looking weapons. Julia yelped as The Doctor pushed her down onto the floor behind the console and then dived and rolled and kicked the legs out from under one of the guards so that his weapon fired into the air and smashed one of the ceiling lights. At the same time, Chrístõ had moved swiftly to grab another of the guards around the neck. His gun also went off erratically, and accidentally killed the third guard. Chrístõ and his older self disarmed the two and rendered them unconscious with variations on the same martial arts. They stood up and looked at each other.

“Not bad,” The Doctor said with a grin. “For a youngster.”

“Not bad for a pensioner,” Chrístõ responded. “Ok, what about disrupting the warp shunt?”

The Doctor bounded towards his TARDIS and emerged from it with a length of thick, insulated cable. Chrístõ looked at it and then began to pull open a panel beneath his own console from where he uncoiled a slightly thinner cable.

“Now we’re cooking,” The Doctor said. He stopped at the TARDIS door and looked at Julia. “You should keep your head down, sweetheart. If any more guards turn up, shut the door and hold on till we get back.”

“What if you both get transmatted back to the planet?” she asked.

“We’ll be in big trouble and so will the city of Canberra,” The Doctor said. “So we’ll try not to do that.” He looked at Chrístõ. “Coming?”

Chrístõ nodded and followed him out of the TARDIS. Julia stayed down on the floor behind the console with Humphrey hugging up to her. She looked up at the viewscreen. It was showing two views at the same time. One was of the engine room outside, where Chrístõ and The Doctor were busy connecting those cables to some complicated equipment. The other showed the view of Earth from synchronised orbit above Australia.

Then the TARDIS rocked and pitched and she fell straight through Humphrey. As she picked herself up, nursing a bruised elbow she saw the view again. Now there was no Earth, no moon. Nothing but a dust cloud. Then she heard the TARDIS door open. Chrístõ and The Doctor threw the cables back in and then hauled the two unconscious guards and one dead one out of the door.

“Mission accomplished,” The Doctor said. “Next stop, dinner in the Black Mountain Tower restaurant, on me. We should just about have time to change into our posh frocks.”

“Well, Julia can,” Chrístõ replied. “I prefer a dinner jacket, and unless something went seriously wrong with your regeneration I’m sure you do, too.”

The Doctor grinned at him and headed into his own TARDIS. Chrístõ set the course and went to change, hoping that really was a joke from his older self.

It was. When the two TARDISes materialised on the observation deck, one disguised as a staff only entrance and the other stuck as a strangely incongruous police box, both men were dressed in sober black with a hint of silver in their tie clips and cufflinks. Julia looked stunning in a pale blue cocktail dress and her favourite diamond earrings and necklace.

“I remember having those made for you,” The Doctor said with a longing expression. But he stood back to let Chrístõ take her arm. He walked beside them as they were shown to their window seats in a revolving restaurant that gave them a completely new view every few minutes. They looked like three people enjoying dinner together without any cares. Nobody could have guessed that they had prevented most of that glorious view from being reduced to smoking rubble.

For most of the dinner their conversation was light and easy and avoided the subject altogether.

“Ok… so why WERE the Deten Cassians hell bent on destroying Canberra?” Chrístõ asked finally as they drank coffee at the end of the meal. “What was it all about?”

“They thought it was a Deten Xassian outpost,” The Doctor answered. “The symbol of the Deten Xassian military is a circle with a double line through it, inside a hexagon.”

“Er…” Chrístõ blinked, trying to work out why that would put Canberra at risk. Then Julia exclaimed loudly. She clamped her hand over her mouth as several other diners looked around disapprovingly then continued in a quieter voice.

“Where we’re going after dinner… the Canberra Theatre Centre… by City Hill… a circular park with a big dual carriageway either end of it… and the whole thing surrounded by roads in the shape of a hexagon… You commented on it yesterday, saying that it looked like the TARDIS console from above.”

“You mean they…” Chrístõ looked at his older self in disbelief. “They seriously thought…. Of all the stupid, ridiculous reasons to launch a genocidal attack. It would be funny if it wasn’t so very nearly tragic.”

“Strange universe, isn’t it,” The Doctor commented. “It still surprises me. You’ve got a lot of it to learn about, still.” He sighed. “I envy you. To have it all ahead of you, to have your ideals intact, before they were ripped to shreds by experience.” He smiled with his mouth, but his eyes were deadly serious. “Looking as young as you but feeling as old as I do isn’t easy.”

Chrístõ didn’t trust himself to answer that. Julia, however, reached out to The Doctor and put her hand over his. He turned to look at her and his eyes lost a little of their darkness.

“Oh, that makes me feel young, again. Thanks, sweetheart,” He turned to attend to the waiter who brought the bill on a small silver tray. He put his credit card into the portable card reader and inserted his pin number before accepting the printed receipt. “I should get going – leave the two of you in peace. Where was it that you were going? Oh, yes. I remember. Melbourne Opera were doing Puccini’s La Boheme. One of our favourites.” He grinned at Chrístõ. “Puccini! I could tell some stories about him. Bohemian days in Milan… But you’ll find out for yourself when the time comes.”

He stood up to go. Julia pushed back her chair and stood, too. She put her arms around his neck and reached to kiss him. Chrístõ stood and shook hands with him. He took hold of Julia’s hand proprietarily as his older self left the restaurant. A few minutes later as he ordered a second round of coffee for himself and Julia he felt a slight fluttering sensation in his hearts and knew that the other TARDIS had dematerialised. He was glad. There was always something a little disturbing about crossing his own time line in that way. The older versions of himself, even ones who looked young, seemed to have so much darkness in their souls. He wondered just what his future held that was so disturbing.

He wondered just what he was going to get up to in Milan with Puccini.

Then he cast aside his concerns for the future and remembered that right here and now he was in a fine restaurant with a beautiful young woman who loved him, and the immediate future involved an opera and nothing more to worry about than that. The darkness of his far future could wait.

RDWF Supports Help For Heroes

|

|

|