The Doctor walked slowly along Kingsland Road. He was feeling the early autumn cold in his bones, already, and the trip to the library – or at least staying there as long as he did - was starting to seem like a bad idea. Susan would surely be home before him and she would worry if he wasn’t there.

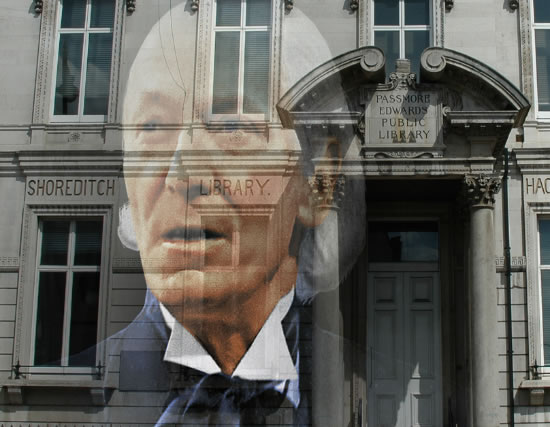

He liked Shoreditch library. It was one of those free libraries built in the Victorian era to allow the lower classes to improve themselves. In those days buildings for the lower classes were given as much attention to detail as Town Halls and Mansion Houses.

Perhaps it was that, or the fact that it was old, like himself, that attracted him. He sat for many hours reading both fiction and non-fiction. He read slowly – just a little faster than the humans around him in the quiet reading room. He found the discipline of reading one page at a time good for his sometimes wavering mind. He always left the library feeling that he had made good use of the afternoon, and that the aspirations of the men who built the ‘temple of learning’ were somehow fulfilled even if he wasn’t one of the lower classes for whom they had provided the service.

The roads were busy. The sound of traffic and pedestrians boiled in his mind. Even the relatively benign hoof-beats and the rolling of wooden wheels on cobbles as a coal wagon pulled by two stout carthorses went by seemed too much. He longed for quiet places, free from noise and bustle. London was too big, too noisy, too busy for him.

A high sided lorry with the name of some furniture shop or other was behind the coal wagon. The driver sounded his horn impatiently. The Doctor cried out in frustration and covered his ears. When the coal wagon turned a corner the lorry accelerated away to be replaced by a double-decker bus in the familiar red livery. Everything seemed intent on making so much noise.

There were side roads that he might have taken, but he wasn’t certain which ones to take and it really WAS getting late. Straight down Kingsland road and right into Nuttall Street, cutting into Hoxton street, then Pitfield street was hectic but it was a little more than a mile home. He might just get there before Susan began to worry.

That might have been possible if his mind had been on the walk home instead of focussing on three other things at once. He missed the turn into Nuttall Street and had walked several hundred yards more before he realised he was in unfamiliar territory. He turned and stared around him. He couldn’t remember for a long, terrifying moment where he was even supposed to be going.

Nuttall Street, yes. That was on the other side of the road, wasn’t it? He stepped off the pavement...

…And failed to see the black taxi that had just pulled out of a side street. He hardly made a cry as the bumper smashed into his legs and he was tipped forward against the windscreen before sliding down onto the tarmac road.

He heard the taxi driver calling out to him. He heard the screech of brakes as cars and buses came to a halt and somebody saying that they would fetch an ambulance then running away urgently.

By the time the ringing bell of the ambulance drew closer he didn’t hear it. He was insensible.

Susan reached Totters Lane a little later than usual. It had been cookery in the last period and she had carefully carried the steak and kidney pie she had made home with her. She wanted it to be a surprise for her grandfather.

She checked, as always, that nobody was watching her before she slipped into the junkyard. She looked around carefully again before she took out her key and opened the TARDIS door.

She was puzzled when she found the console room empty and quiet. She put the pie in the kitchen area and put the kettle on. She made a pot of tea and sat down to drink a cup. Her grandfather still wasn’t back, but she remembered it was his day to visit the library. Perhaps he was so absorbed in the books he lost track of time.

She did her homework. It wasn’t difficult. Maths was not very advanced in English schools. The history essay was interesting. The hard part was trying not to sound too knowledgeable. There was so much more she could have said about the expansion of the British Empire than the school syllabus expected of her.

When it was done, she looked around at the still silent console room. She began to feel a little uneasy. Grandfather ought to be home by now.

What if something had happened to him? It was why he was always worried about her. He insisted that she come straight home from school every night without stopping off at record shops or cafes like the other girls. It was why she had so very little social life beyond school and sometimes felt a little lonely.

They lived in constant fear of being found out as aliens, captured, imprisoned, interrogated, even operated on to find out their biological differences. Grandfather talked about it all the time. He reminded her that humans were paranoid and suspicious even of each other, and their scientists always looking for new weapons against their perceived enemies. Even the relatively benign British government would want to use them in their fight against the Russians.

It was hard living like that, watching everything she said, everything she did, even simple things like buying sweets or getting on a bus, seeing every innocent person in the street as a potential enemy who might betray their secret.

But had his warning been more than paranoia, after all? Was it possible that Grandfather had been captured. Was he a prisoner of those government scientists.

No. She shook her head and told herself that she was being silly. He was just late. That was all.

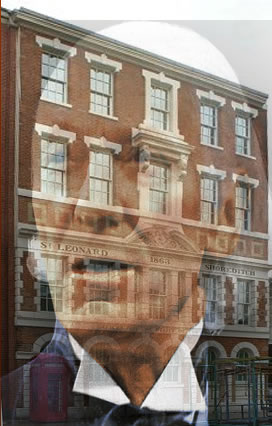

St Leonards Hospital was not very far from where The Doctor was knocked down by the taxi. It wasn’t long before he was transferred from the ambulance to a trolley and then to a bed in the emergency department. A doctor came to examine him and pronounced that he had a broken arm and concussion, but nothing more serious.

“I don’t like the sound of his heart, though,” the doctor added. “It’s very rapid. And I’m not happy about the fact that he hasn’t started to come around, yet. I think I’d like to have some tests, done. Meanwhile, make him comfortable in the geriatric ward. Do we know who he is, at all?”

“No, doctor,” answered the staff nurse in attendance at his side. “His coat contained very little – only some small change and a library card. The name on the card is John Smith… but that really doesn’t tell us much. The name is so very common, and there is no address.”

“Well, when he regains consciousness he might be able to further his details. Meanwhile, keep a close eye on him. If his condition changes overnight we might have to consider investigative surgery.”

“Yes, doctor,” the nurse agreed. The physician passed along to his next patient and she made arrangements to have the mysterious John Smith transferred to the geriatric ward.

Susan was truly worried, now. It was dark outside and a thick fog was closing in. If her grandfather was still walking in that, he would be in great difficulty. The fog and the cold caused him terrible problems with his chest. Sometimes his susceptibility to quite Human frailties frightened her. What would become of her if he became seriously ill? What if he died?

Again she was letting herself worry too much. She tried to read a book, an adventure novel rather than a text book or history. She enjoyed that sort of diversion, usually.

The Doctor woke slowly, aware that he was in a strange bed and that he was hurting. He tried to touch his aching forehead and noticed the sling restraining his arm.

He opened his eyes fully and saw hospital curtains and another bed a few feet away where an elderly man was sleeping fitfully.

So he was in a hospital. But why? He closed his eyes again and tried to remember. Yes, of course. The accident. London – so much traffic. It was hard to look everywhere at once. That was why he worried about Susan so very much.

Susan! His hearts quickened as he thought of her. The poor girl would be frantic. Would she have enough sense to stay in the TARDIS and wait? It was dark outside. She might get lost wandering around London looking for him. If only they had some means of contact other than the primitive public phones of this time. But he didn’t dare issue her with a pocket communicator in case it was discovered.

Susan was thinking about those pocket communicators, too. Of course it was a terrible risk carrying any technology that was not of this time, but at least she would be able to call him and find out where he was.

Still sitting on the sofa, she turned her head to look towards the console in the centre of the clinically white and futuristic room. The focus of her gaze was a small switch covered by a glass bell. If she truly was abandoned due to some unforeseen incident….

No, not unforeseen. Her grandfather had considered the possibility. He had considered his own death or disability making it necessary. That was why the switch was there. If there really was no other choice she could send an emergency signal back to her home world. They would come and get her. She was only a child when they left. She would not be blamed for her grandfather’s actions. They would look after her.

But the thought chilled her. What she remembered of that world was vague. She knew that it was very beautiful, and the people very clever. But she also knew that her grandfather was still angry with the government, and they with him. She wondered if she could be happy in a society that he had been at such odds with.

And besides, she was very happy here on Earth, despite having to live a lie. She liked the people, the history, and especially the music of 1960s London. She didn’t want to leave all of that.

Most of all, she didn’t want to lose her grandfather. She was closer to him than it might seem, sometimes, when he was in a brusque mood and answered her shortly or not at all. She loved him deeply and he loved her. They needed each other. They were family – and that meant as much where they came from as it did on Earth.

The Doctor closed his eyes again and kept very still. He didn’t want any of the nurses bustling about the ward to know that he was conscious. He didn’t want the questions that were bound to be asked.

They must have noticed already that he was different. His hearts were a give-away, and if they had taken a blood sample that was certainly going to puzzle somebody.

He ought to get away before somebody decided he was too different to be Human. If that happened, then the nightmare he had so often warned Susan about would be upon them. Scientists would want to know all about them both. They would want to investigate their double hearts and their blood that didn’t match any known Human type. They would want to see if anything about their bodies could be replicated and used in their pointless, useless Cold War with other humans who lived in a different part of the same world.

He had to get away, but how could he? He was still very dizzy from the head wound and his arm was excruciatingly painful. He was dressed in a hospital gown and had no idea where his clothes were.

He closed his eyes again as the lady with the tea trolley came by. She placed a cup on the table next to his bed and quietly moved away, assuming he was asleep and would drink it when he woke.

Tea seemed like a very good idea, but he didn’t want anyone to know he really was conscious, now. He would just have to enjoy the smell of the milky liquid so close to where he was lying.

Susan dropped to sleep on the sofa out of sheer emotional exhaustion. She woke with a start to hear the old-fashioned clock in the corner of the console room striking eleven.

Eleven o’clock. On a Friday night a lot of her school friends would expect their father’s home any time now – after the pubs closed. But her grandfather wasn’t that sort of man. He didn’t go to pubs. He didn’t drink beer with friends.

Was that possible? A brief hope rose in Susan’s hearts. What if he got talking to somebody at the library and decided to go with them to a public house. There were plenty of those in East London and her grandfather was so very good at losing track of time when he was pre-occupied with something.

If it was only that simple! If it was, she would give him a telling off, to be sure, for worrying her like that. But if it WAS something so normal, so ordinary, then it would be quite wonderful in a way. It would mean that he had come to understand the very same things she understood about London and the humans who lived there – how fascinating they were.

“Oh, grandfather, let it just be that, please!”

The Doctor lay quietly as the hours ticked by and let his mind reach out to the patients in the other beds around him. They were all old men, of course. Their ailments ranged from a case of chronic angina to emphysema and gallstones. The gentleman in the bed opposite to him was the most serious. He had a respiratory problem that was causing the doctors concern.

He was close to death, in fact. The Doctor could see that as he reached out and touched his mind. Mr John Smithson was in his last hours. Semi-conscious, he was thinking of his family, all of them far away, a daughter in Canada, a son in Ireland, his grandchildren with their parents. His wife was long dead, so was his brother. There was nobody to be with him at this time. All the same, he was content. He had worked hard all his life, brought his children up as best he could, seen them get good jobs and good marriages. There was little more that a man could hope for.

The Doctor understood that sentiment. Once he had wished for little more. He still wished it for Susan if it could be contrived somehow while they lived this wandering gypsy life of theirs. But whether he could die content having achieved that much he was less certain. He envied Mr Smithson his contentment.

He stayed with the dying man through the final hour, listening to his prayers, sharing the memories that floated in and out of his mind, both becoming more fractured and more fleeting as his hour approached.

“There’s nothing to be afraid of.” He thought he heard the old man say that – as if he knew that his last moments were being watched so closely.

“I know,” The Doctor replied. “Indeed, I know.”

Then the thoughts were gone. The life was over. Mrs Smithson’s soul reached for whatever afterlife he believed in and his body was still. It was just gone midnight and the night shift nurses had not seen his quiet passing.

Susan’s one hope drained away as midnight approached and her grandfather still didn’t return home. At last she made a desperate decision. No, not the switch – not yet. Not until she was certain he was really gone.

She put her coat on and stepped out of the TARDIS. The cold night pinched her face at once and outside the yard the fog was nearly impenetrable. She turned left, though, and walked slowly and carefully until she reached the red phone box on the corner of Totters Lane. It had stood there like a beacon of solace to the lost all the time she had lived in the lane. She stepped inside and reached for the receiver. She dialled 999 and waited for the operator to respond.

“Hello, can you help me, please?” she asked, swallowing a lump in her throat. “My grandfather is missing.”

“Please wait,” the operator said. There was a click and a short silence before somebody said ‘Police, how may I help you?”

She repeated her problem, sounding, without intending to do so, very young and vulnerable and very, very scared.

“What is your name, dear?” the police telephonist asked kindly.

“Susan,” she answered, then hesitated about her surname. Of course, it wasn’t really Foreman. That came from the name on the gate of the abandoned junkyard where the TARDIS was parked. “Susan Smith,” she said quickly, remembering the name that her grandfather sometimes used.

“And where do you live, Susan?”

That was when she realised that they meant to send a policeman to talk to her. That was when she knew that the police couldn’t help her.

“Are you all right, Susan? Are you on your own? How old are you, Susan?”

“I’m… sorry… I can’t….” she stammered and dropped the receiver back onto the cradle. She backed out of the phone box and turned to run through the fog, back to the junkyard, to the TARDIS, and safety.

Could they trace the call? Would there be police cars coming down Totters lane, investigating a hoax call? Would they be looking for Susan Smith?

Had she made the situation worse? What would grandfather say if he knew she had done something so silly?

But what else could she do?

“Grandfather, where are you?” she whispered softly as she lay down on the sofa and buried her head in an old scarf of his that smelt strongly of his pipe tobacco – the smell she most associated with her grandfather.

The night nurse found that Mr Smithson had died when she next made her rounds. There was a flurry of activity around the bed and then the curtains were drawn and he was left alone.

“They will send somebody up for the body, soon,” the night nurse said to her subordinate. “Best not to let the other patients know. It will only upset them.”

The ward full of sleeping men was quiet again. The night nurse was filling out the paperwork that went with a natural death on the ward. Mr Smithson wasn’t the first. The hospital had once been attached to a workhouse and its patients were usually in extremis when they came to the wards. It had seen service in two world wars and outbreaks of influenza, scarlet fever, whooping cough and all manner of diseases that spread through narrow streets and crowded houses. Mr Smithson was not likely to be the last old man to die in the wards.

But his paperwork had to be done.

The Doctor rose from his bed, wincing at the pain in his arm and swaying dizzily from the concussion to his head. He moved quietly across the ward and opened the curtains around Mr Smithson. He felt a little guilty about the lack of respect, but he had a plan for getting out of the ward and he needed the late gentleman’s unwitting assistance.

He needed the chart that hung on the end of the patient’s bed. The name was such a close coincidence it couldn’t possibly have been contrived. He swapped it with John Smith’s chart and closed the curtains around his own bed. He lay down quietly with the sheet pulled up over his head.

As he expected it wasn’t very long before a pair of orderlies came with a trolley. He kept very still and held his breath as he was transferred to it, still covered by the sheet, and wheeled away out of the ward and down a long corridor, then a short descent in a lift and another corridor.

This brought him to the mortuary. It was still and quiet at this time of night and the orderlies left the trolley in an alcove with the chart detailing Mr Smithson’s last illness lying on his chest.

When he knew he was alone The Doctor rose from the trolley. He moved slowly through the mortuary, trying cupboard doors. He soon found what he needed. Clothes taken off the bodies were labelled and sent to be laundered. They were brought back and stored until the undertakers arrived to prepare them for the funeral.

The Doctor found clothes that fitted him. Getting dressed with one arm out of action was a painful business, but he managed eventually. Then he slipped out into the dimly lit basement corridor and followed the signs leading to a fire exit. He emerged at the back of the hospital in the dark, bitter, foggy night. Nobody noticed him leave. He was a shadow among shadows.

He was slightly surprised to find that the hospital was not very far from the route he was meant to take home. He walked carefully along the now much quieter Hoxton Road, turning into Pitfield Street. The lights on the front of the Gaumont cinema were being turned off after a late Friday night showing of some film The Doctor had never heard of. He walked on and turned down Haberdasher Street and into Totters Lane which was cold, dark and foggy, but familiar enough that he didn’t need to worry.

“Good evening, sir,” said a constable who emerged out of the gloom. “Rather late to be about, isn’t it?”

“Yes,” The Doctor replied. “Yes, it is. I was inadvertently delayed. I am going home right now.”

He didn’t sound drunk and he walked in a straight line. Though his clothes looked a little askew and he held his arm stiffly, the constable had no reason to detain him.

“Goodnight, sir,” he said, touching his brow politely.

“Goodnight to you,” The Doctor replied. He waited until the policeman had gone and then slipped in through the gates of IM Foreman’s scrap merchants yard. He looked around once, very carefully, before opening the TARDIS door and stepping inside.

Susan was asleep on the sofa, her head resting on his old woollen scarf. He reached out gently to her with his good arm. She woke with a start and gave a frantic cry.

“Grandfather!” She wrapped her arms around his neck and hugged him tearfully. “Oh, grandfather, I was so worried.”

“I had a little mishap,” he told her. “But everything is quite all right, now.”

“Are you sure?” She saw his bandaged arm in the sling and was immediately concerned.

“I am old. My regenerative powers are not what they ought to be. The arm will take two or three days to heal. But I will be fine after that. no need to worry.”

“But I DO worry about you, grandfather. I thought the worst had happened.”

“It didn’t, and we may be thankful. Would you make me a cup of tea, my dear. I am quite thirsty for such a delicious beverage.”

“Yes, of course,” Susan replied. “If you’re hungry… I made a steak and kidney pie at school. Would you like some?”

“Let’s keep that for tomorrow’s supper,” he answered. “When we can fully appreciate it. The tea will be just fine for now.”

Susan made the tea, along with sandwiches and biscuits because she was hungry now, and she was sure her grandfather was, too. As she brought the tray back into the console room she glanced at that switch under the glass. One day, perhaps, she might have to break the glass and press that switch, but not today.

Not this time.

|