The

TARDIS materialised beside a placid looking river meandering through a

wide, grass covered flood plain. In the distance were some snow-capped

mountains that must have been its source. It was a pleasant looking spot,

anyway, and when The Doctor suggested a short stroll in the sunshine,

Donna was happy to put on sensible shoes and join him.

The

TARDIS materialised beside a placid looking river meandering through a

wide, grass covered flood plain. In the distance were some snow-capped

mountains that must have been its source. It was a pleasant looking spot,

anyway, and when The Doctor suggested a short stroll in the sunshine,

Donna was happy to put on sensible shoes and join him.

“This really is another planet, isn’t it?” she asked. “It looks just like Earth, a nice part of Earth, anyway. South of France, maybe. Although I’ve never been to the South of France, so I wouldn’t really know. But this is how I always thought it would look.”

“It will have been terraformed to look this way,” The Doctor said. “This is one of the colony planets that the Earth Federation of the 24th century prepared for Human immigration. Like Beta Delta III, where we saw the New Sydney Opera.”

“I love that,” Donna said. “The idea that in… about three hundred years from my time, people will actually move to new planets. Beautiful, wonderful planets with rivers and grass. Only… does that mean they’ve mucked up the Earth so much that they have to move? Are they going to muck up this place?”

“No, the Human race got the message just in time and stopped messing up planet Earth. It’s ok, except a bit over-populated. That’s why they started to encourage colonisation of suitable planets. And mostly they looked after them quite well. The Beta Delta system is charming. The cities tend to look like one big garden suburb, but they’re ok. Then there was Xiang Xien. That was colonised by Chinese settlers, and they abandoned technology and returned to the agrarian, semi-feudal system of 18th century Imperial China. And it’s a lovely place. I’ll take you some time. And…” He smiled as he thought of Forêt, another colony planet, though an accidental one, where the descendents of French colonists made a unique and beautiful world for themselves. “Yes, the Human race has made some good homes for itself.”

Then he looked around at what, to Donna, was a paradise planet, warm and beautiful. He frowned.

“What’s wrong?”

“I’m not sure,” he answered. “This planet only has fifty Human beings living on it. The colony ships used to bring thousands at a time to establish towns and infrastructure. Fifty doesn’t seem right. It suggests some sort of disaster.”

“Oh.” Donna looked disappointed. She had been feeling proud of her species and its achievements, but the thought that they had failed in this instance made her sad. She wasn’t even sure why she should feel that way. After all, The Doctor had just told her how successful the colonisations were elsewhere. But she felt deflated by the idea that this one planet just hadn’t worked out right.

“What sort of disaster?” she asked.

“Could be anything,” The Doctor replied. “Plague, famine, most likely. I intend to find out. The fifty lifesigns were all concentrated somewhere this way. A village, community, habitat, vien, conglomeration…”

“Monastery?”

“Well, not usually,” The Doctor answered. “Though I suppose…”

“That looks like a monastery to me,” Donna said, pointing to the building that came into view as they rounded a stand of chestnut trees at a bend in the river. A series of buildings, rather, with an outer wall of grey-cream stone and the peaks of several tiled roofs showing above it, not including what was obviously a church with a tall, graceful spire.

“Yes,” The Doctor admitted. “Yes, it does look like a monastic sort of place. How odd.”

“Well, it looks sort of… normal,” Donna pointed out. “It’s not a disaster area.”

“No, it isn’t. But it’s still a bit of a mystery. Let’s go and say hello.”

He stepped forward with a long, fast stride. Donna ran to match his speed before he realised and slowed down a little, and they reached the monastery door without her needing to gasp for breath.

The Doctor was impressed.

“It’s real,” he said. “This is a real, strong, wooden door. These are real stones.” He stroked the warm looking stones, admiring the way they were cut and mortared together. They were a kind of sandstone, with quartzlike grains that caught the sunlight. He shocked Donna by actually pressing his tongue against one of the stones and tasting the minerals.

“Yes,” he said out loud. “From the Demeter IV quarries. The best building stone in the galaxy comes from Demeter. But this is no flatpack, prefabricated building. Some hard graft has gone into these walls. No more than about ten years ago, I’d say. There’s only a very little weathering on the stone.”

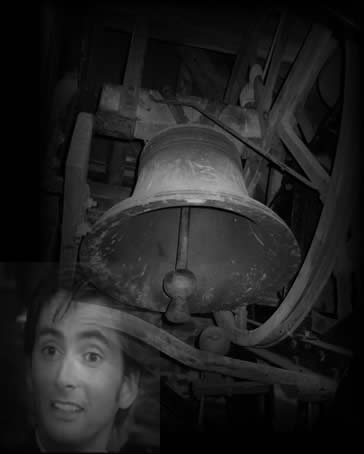

“When you’ve finished trying to eat the wall, are we going to ring the bell?”

“What bell?”

“That bell, dumbo,” Donna answered before she yanked the rope pull beside the door. A bell sounded somewhere inside.

“There are fifty people on the whole planet,” The Doctor said as they waited for an answer. “And they’re all inside these walls. Who do you suppose they expect to ring the bell?”

“Oh, don’t get clever,” Donna answered him. “That’s like one of those ‘if a tree falls in the woods, does anyone hear it,’ kind of things, isn’t it.”

“No, I just wondered who visits them, that’s all.” He was going to say something else, but there were sounds of somebody lifting a heavy iron latch and then the door swung inwards.

“Blessings be upon all within this place,” The Doctor said, bowing his head respectfully to the monk who opened the door to them. He was trying not to look too astonished by their appearance. He, himself, was a tall, thin, angular faced man in his late 40s or 50s, wearing a long brown monks habit tied at the waist with a cord. He was holding a hoe, which Donna supposed might have served as a weapon if they were hostile. He set it aside to respond to The Doctor’s respectful greeting with a handshake.

“I’m The Doctor, this is Donna Noble. We are visitors to this planet,” The Doctor added. “Come to pay our respects to your people, here.”

“You are most welcome,” the monk answered with what Donna would have called a North-Eastern accent. He stood back and invited them over the threshold with a friendly gesture. “I am Brother Michael. This is the Monastery of Saint Francis on Assisi.”

“Don’t you mean St Francis OF Assisi?” Donna asked.

“No,” The Doctor gently explained. “Assisi is the name of the planet. In honour of the founder of their order. Is that right?”

“It is,” Brother Michael confirmed as he led them along a path through the garden within the monastery walls. Several monks were working among the growing plants. Donna noted that they were mostly vegetable crops – tomato vines, cabbages and carrots, onions, something that might have been watermelons. The nearest things to decorative plants were to be found in the herb garden. There were archways leading to separate areas which looked at a glance like an orchard and a vineyard.

“Beautiful,” Donna commented about it all. “You grow all your own food. Of course, you would have to.”

“We have wheat, oat and barley fields beyond the walls,” Brother Michael told her. “And grazing for a small herd of cows. We produce enough for our needs.”

“Can’t be bad,” Donna said.

“We have been fortunate,” Brother Michael responded. “We have had good harvests each year since we began. And we shall be glad to share our bounty with you, the first guests who have come to us since the work began.”

“The first?” The Doctor frowned again. He had been smiling as he looked around at the garden. He could see that things were going well for the brotherhood. But it still seemed strange to him that they were the only souls on the planet.

“Come within,” Brother Michael said as they reached the front door of the monastery itself. The Doctor bowed his head respectfully before he stepped into the cool, peaceful anteroom. It was an almost empty room, with a stone flagged floor and nothing adorning the wall except a large crucifix. A lifesize statue of St Francis stood opposite the outer door, beside the door to the inner part of the monastery.

“It is almost time for our midday meal,” Brother Michael told them. “Come to the refectory and be seated before the brothers join us.”

“Refectory sounds good to me,” Donna said. “But, is it all right? I mean… this is a monastery. I’m a woman…”

Brother Michael smiled warmly.

“It isn’t so long since I took orders that I had forgotten the concept. It is perfectly acceptable for you to visit and take food and drink with us. Come and sit.”

The refectory was a big, airy room with windows high in the walls that made it bright. Again the floors were plain flagstones and the walls had only a few religious symbols on them. Another crucifix and a relief in bronze or some other sort of metal, of a bird within a tongue of fire. Brother Michael explained that it represented St Francis, a man whose heart burned with religious fervour and who once preached a sermon to the birds.

“Why?” Donna asked.

“Because he believed that all of Creation was worthy to hear God’s Word of love,” Brother Michael said.

“Oh, ok. Fair enough.” Donna wasn’t entirely sure what to make of it. She had never really been a church-goer, although there were pictures of her mother in a hat, holding her as a baby in a christening gown. But Donna thought that was probably more to do with her mum wearing a posh hat and having a reception afterwards for all her friends than anything to do with religious belief. She herself had never really had any deep religious convictions. She hadn’t really said a formal prayer since her last school assembly. As a bell sounded and the refectory began to fill with monks who came from their work in different parts of the monastery, she felt a little bit of a fraud sitting there among them.

And what about The Doctor? He came from a different world, a different species. He wasn’t even Human. She wondered if he believed in God – or any god.

Did the religion people believed in on Earth still count on other planets, anyway? Obviously it did for Brother Michael and his colleagues. But what about The Doctor’s world, or any other world, for that matter?

The Brothers all stood at their places, and one of them led a short prayer. Donna watched The Doctor as it was said. He didn’t join in with the ‘amen’, but he did seem to mark it respectfully with a very slight nod of the head. Then they sat and the food was served. Tomato soup with herbs and barley bread – fruits of their efforts outside, she supposed. As they ate, The Doctor asked Brother Michael and the others around him about their monastery and how they came to be there.

“We arrived ten years ago,” explained a sandy haired man called Brother Andrew. “We brought all the materials to build our community here and rations to last us through the first growing season. It was hard work, but we all pulled together, putting stone upon stone until we built the dormitories and refectory, kitchen, hospital, and the church, of course, the most important building.”

“Ten years to do all this?” The Doctor was impressed. “Magnificent endeavour. You are to be congratulated.”

“It is not yet finished,” Brother Andrew told him. “It will be today, by God’s grace, when we raise the bell into place in the belfry.”

“Brothers Andrew, Simon and Paul cast the bell themselves,” Brother Michael told him. “It will be a proud moment for us all when it rings out across the countryside.”

“I am sure it will be,” The Doctor answered. “But…”

“What is the point?” Donna asked. “When there’s nobody to hear? I mean, that really is like the tree falling in the woods…”

“Yes, I was wondering about that,” The Doctor added. “This colony has never been colonised, except by yourselves…”

“We came out here first, to ensure that the new settlers would have the blessings of God upon their endeavour,” Brother Michael answered. “A church for them to pray in, our hospital and our medically qualified brothers to tend them if they are sick.”

“Ah,” The Doctor nodded in understanding. “You are here to pave the way for the colonisers.”

“Exactly.”

“But… shouldn’t they have started arriving by now?” Donna asked. The Doctor smiled at her. That was the question he had intended to ask. “I mean, ten years…”

“Yes,” Brother Michael admitted. “That does puzzle us, sometimes.”

“Can’t you phone and find out where they are?” Donna asked.

“We did not bring any form of communication,” Brother Michael replied. “We planned to live here in the same conditions that our antecedents did when they founded colonies in Africa or China, or the frontiers of nineteenth century America. We brought materials, and we brought ourselves with the skills to build and to cultivate crops, to cast metal. But we had no need for communication beyond the planet.”

“I could try to find out what the problem is,” The Doctor offered. “Perhaps they’ve simply forgotten you’re here. Later, I should be glad to make enquiries on your behalf.”

The monks all looked at each other, then at The Doctor, as if his suggestion was a new and startling one.

“Yes,” Brother Michael answered him. “Yes, that is a kind offer and we should be glad to hear any news from Earth that you can obtain.”

“That’s sorted, then,” The Doctor said with a wide smile.

“But first,” Brother Andrew insisted. “It must be God’s will. He brought two visitors as witnesses to this proud day when we raise our bell and ring it for the first time. You must stay and watch that work being completed.”

“Oh, indeed,” The Doctor told him. “I wouldn’t miss that for the world.”

Donna was interested, too. She had no idea how they planned to get a bell up into the belfry, almost three-quarters of a way up the tall, slender spire. She came from London, a city with churches of all sorts in it. She had heard church bells on a Sunday. She had heard the chimes of clock towers. But most of those churches were at least a century old. She had never seen a new church being built. She had never seen a bell being installed. Just how was it done?

The answer was simple – it was done with a huge amount of effort on the part of the Brothers. The bell, a huge bronze thing, as high as Brother Michael and as wide as three of his colleagues standing beside each other, was sitting at the bottom of the spire, attached to long, thick ropes that went up to the belfry, where they were fixed to a guide wheel and fed out of the windows and down to the ground where two lines of the youngest and fittest Brothers got ready to take the strain. Others were up at the window to control the ascent. Brother Andrew gave the word and they began to haul, slowly, carefully. A muted clanging noise was heard from within. The clapper was muffled in woollen cloth to protect it as the bell slowly ascended. Even so, the noise told those outside just how far up the spire it had gone.

Donna watched the brothers continuing to haul, taking rests every so often, but never letting go of the ropes. If they did, it would be a disaster. The whole thing would come crashing down.

“Couldn’t you do something to help them?” she asked The Doctor. “Like… I don’t know, fly the TARDIS up there and pull the ropes, or do something with gravity to make it easier to pull it.”

“Yes, I could,” he answered. “But I wouldn’t insult them by offering. They have built all of this with their own bare hands, by their own labour. To have a stranger come along and make it easy would be completely wrong. They have a right to be proud of their own achievements. Except they won’t be, of course. Because pride is anathema to them. They will do this and then thank their God for giving them the strength to do it.”

He smiled as he said that. He admired their dedication and effort. If they were not allowed to be proud, he was.

“This is what I like about your species,” he added. “When you achieve great things by your own ingenuity and determination.”

“Didn’t your species achieve anything like this? You don’t have spires and bells and stuff?”

“Oh, yes,” he answered her. “We had towers, spires that would dwarf this one, their points tapering so slender that they swayed in the breeze, majestic buildings with great domes rising up into the sky, bridges that almost defied the laws of physics. But we built them with every kind of advanced technology we could devise. This is real achievement. Oh, yes. This is what it’s all about.”

Donna didn’t exactly understand, but she caught his enthusiasm for this Human endeavour. She still wanted to ask him what he really believed in. Before she could think of a way to frame the question, though, there was a collective gasp from the Brothers up in the belfry and a panicked scream from inside.

“Stay here,” The Doctor said to Donna, though he knew she probably wouldn’t tale any notice of him. He looked at the Brothers holding the ropes. “Don’t pull any more. Not yet. Tie them off if you can. If not, then hang on for dear life. Don’t let the bell slip.”

He dashed into the spire and looked up. He could see all the way up to where two monks were lying across the heavy beam where the bell would swing. They were ready to bolt it into place. A third man was hanging by one hand to the supporting ropes that hung down the side of the bell. His other arm was bent under him in an unnatural way that suggested it was broken. He couldn’t hold on for much longer. His fellow Brothers couldn’t reach him, even from the wooden stairs that spiralled around the walls.

“I’m falling,” the Monk cried as his grip failed. He slid down the side of the bell almost in slow motion, but then gravity took over his as he fell into empty air.

“Gravity, smavity,” The Doctor muttered as he adjusted his sonic screwdriver and aimed it at the falling man. There were gasps all around as the falling body slowed almost to a stop and then began to descend gradually as The Doctor lowered his outstretched arm. The gasps of horror turned to ones of awe as he landed safely on the ground. The Doctor adjusted his sonic screwdriver and examined his injured arm.

“It’s a clean break of the radius. Somebody can take you along to the infirmary. You’ll be right as rain in a few weeks.”

Two of the Brothers took the injured man away as The Doctor stepped outside and told the others they could continue hauling on the ropes again.

“Yes, I can do things with gravity,” he told Donna. “I hope they will forgive me introducing advanced technology in extremis.”

“I’m sure the one who didn’t get splattered over the flagstones will,” Donna answered. “That was really clever.”

“It was nothing short of miraculous,” said Brother Andrew as he watched the work continuing. “Doctor…”

“It is not a miracle,” he insisted, holding the sonic screwdriver in his open palm. “It’s just technology.”

“Perhaps the miracle is not your technology, Doctor,” said Brother Michael. “Perhaps the miracle is that you came here on this day when you were needed. That is what we should thank God for – That He brought you to us.”

“If that is what you think, then I cannot argue,” The Doctor replied. He pocketed his sonic screwdriver and stood watching the continuing work. Donna looked at him and realised something else about him. He did amazing things, like saving the life of somebody who would have died if he hadn’t been there. And he took absolutely no credit for it.

She was impressed.

“It is almost done,” Brother Michael said. “Shall we go to your ship and send that communication, now?”

“Yes, good idea,” The Doctor answered. He turned and headed towards the gate with Brother Michael. Donna again found herself running to catch up with the long-legged stride of the two men. They slowed down outside the monastery gate and the walk back to the TARDIS was a pleasant, leisurely one.

They were near the TARDIS when a sound made them all stop and turn around. It was a church bell ringing out. They were a good half mile away and the sound was still wonderfully sonorous. It a delightful sound.

Brother Michael looked at The Doctor with eyes glistening with joyful tears. He was smiling broadly.

“Congratulations,” The Doctor told him with a smile that matched his. “Your bell is ringing.”

“It’s wonderful.”

“It is. Now, let’s find out why there’s nobody here to listen to it except us.”

He stepped into the TARDIS. Donna followed, then stepped back outside and smiled reassuringly at Brother Michael.

“Come on in,” she said. “It’s ok. Just don’t ask the obvious question when you look around.”

Brother Michael did as she said. He stepped inside the TARDIS and refrained from asking why it was so much bigger on the inside. He went to The Doctor’s side and watched as he typed incredibly fast at the computer database. In a matter of seconds he had the information they needed.

“No!” The Doctor was nearly as horrified as Brother Michael when he saw the report sent to the colonial department of the Earth Federation almost seven years ago.

“They cancelled the colonisation programme because a geological report said that the planet was tectonically unstable?” Brother Michael’s face froze in disbelief. “You mean… seven years ago, they decided not to send anyone here.”

“It would seem so,” The Doctor answered. “Tectonically unstable? Have you had any problems? Earthquakes, landslides, lakes turning acid, anything of that sort?”

“Nothing at all,” Brother Michael replied. “This planet is as near to paradise as we could hope. Even the winters are mild.”

“Then what’s all that about?” Donna was hardly an expert. But even she understood in principle the computer model on the screen. It was a speeded up projection of what would happen to the planet in the future, with earthquakes and volcanoes devastating the land, the seas boiling from underwater volcanic activity, and the paradise turning to a wasteland before the planet actually exploded into asteroid size fragments.

“That’s what’s going to happen to this place? How long will it take? That’s speeded up, obviously…”

“The model suggests a time frame of at least four hundred years before the planet would be completely unviable. It sounds a long time to humans, but geologically it’s a very short time. And certainly it would make the planet unsuitable for colonisation. These planets are investments for the long term future of the Human race, not for a few generations to settle and then have to move on again.”

“Assisi is doomed?” Brother Michael’s voice was filled with dismay. “All that we have worked for, all we have done, will be gone?”

“That’s what the data says,” The Doctor explained. “If you’ve not experienced any problems, then you’re probably all right, at least for your own lifetime. The worst effects of the instability might not manifest themselves for another century or more.”

“But we built the monastery, the church, for the future generations. We intended it to stand for a millennia or more as testament to Human endeavour and Faith.”

“Yes, I know. I’m sorry. Believe me when I say I fully understand.”

“It’s not fair,” Donna said. “It’s so not fair. They all worked so hard. And this planet… it’s so beautiful. Doctor, is there nothing you can do to help?”

“I can come back in four hundred years and help with the final evacuation,” he said.

“That’s all?”

“That’s all. Donna, I’m NOT a god. I can do some clever things with gravity. But this is too big. When a planet dies… it dies. It’s meant to happen. Michael would say ‘God’s will’.”

“Yes,” Brother Michael sighed. “Yes, it is hard for us to understand, but this must be part of His plan, as bitter a blow as it is to us. Perhaps we were too proud of our achievements and needed to be shown that we are, ultimately, dust?”

“Something like that.”

“Even so. It will be hard for them. All our efforts. With your permission, Doctor… If I could use your remarkable machine to contact Earth… I should speak to the Archbishop. We must make preparations to leave.”

“Leave?” Donna was appalled. “But The Doctor said…”

“Our reason for coming here was to prepare the way for colonisation. We were to give pastoral care to the families who would settle in this valley around us. If there are to be none, then we have no justification for our continued existence as a community. We must move on to other places where there is need of our work.”

“But after all you’ve done here?” Donna was almost in tears. She wasn’t sure she even believed in the Faith the Brothers had in such abundance, but it grieved her that their work was to come to nothing. She turned to The Doctor to plead with him again, but he was absorbed in a study of the computer model that spelled such disaster. She caught her breath. He had thought of something. She was sure of it. She waited for him to speak.

“Michael,” he said at last. “From what direction does the sun rise in the morning here?”

“The East, just as it does on Earth,” Brother Michael replied. “Why? Is it…”

“I’m not sure. It could be just a mistake. Perhaps the model is upside down. But it looks like a west-east axis instead of east-west.”

“Does that make any difference?” Donna asked. “Oh…. Don’t tell me. The model is playing the wrong way round? It’s going back to when the planet was formed, not forward.”

“I’m afraid not,” The Doctor answered. “Though that’s an interesting theory. This IS a genuine projection of the lifespan of a planet. I’m just not sure… Donna, close the door. Michael, I’ll bring you home in a bit. But first, let’s have a look at Assisi from another angle.”

Donna ran to do as he said. She was still by the door when the viewscreen showed the TARDIS in orbit above the planet.

“Actually, let’s open the doors again,” The Doctor told her. “Michael… go and enjoy the view with Donna. She loves getting a birds eye view of a planetary orbit. I think you will, too. Just enjoy the ride while I do the driving.”

Donna held out her hand to him. Brother Michael went to the TARDIS door. He was rather bewildered at first to look down from the threshold at so many miles of empty space and the planet far below. Donna assured him that a force field would stop him from falling and invited him to sit and watch as The Doctor put the TARDIS into a slow orbit all the way around the planet of Assisi.

It was a very beautiful planet. Donna remembered what The Doctor had said about terraforming. She had heard the word a couple of times on programmes like Star Trek and understood it to mean that the planet had been changed, deliberately, to look a bit like Earth. If so, it was a nice job. The landmasses weren’t the same shape, of course. Nor were the oceans. But it had everything she associated with her home planet – two frozen poles, a hot equator where there seemed to be deserts, whole continents of wooded areas, tropical rainforests and miles of temperate pine forests with snow-capped mountains rising from them, tropical islands in the oceans, great rivers winding across the landmasses. It was beautiful, pristine, intended as a fresh start for Human beings, a chance not to make the mistakes they made on Earth. And she felt sad all over again that it wouldn’t happen.

She hardly dared look at Brother Michael. He was watching the view intently, and she thought he must be feeling the same things she was, but ten times worse, because he had been here all those years, and he had called it home. Even with his faith, his belief that this was part of God’s plan, it must be hard for him to accept.

“Come over here, both of you,” The Doctor called as they completed the orbit and hung over the place where the Brothers had built their monastery. They were too high to see anything of it, but they knew it was there. Donna closed the door and the two of them joined The Doctor at the console. They looked, without understanding at first, at another computer model of a planet, showing all of the layers from the crust, the tectonic plates below, all the way to the molten core.

“This is a stable planet with no immediate problems. And when I say immediate I mean for the next two or three thousand millennia. There will be the odd earthquake or volcano. Any living planet has them. There are a couple of fault lines where you really wouldn’t want to build major cities. Especially not ones named after Saint Francis. But there is no danger of the planet pulling itself apart. It will last for billions of years.”

“Is that… somewhere you think the Brothers could move to and start again?” Donna asked. “Are you thinking of taking them?”

“No,” he replied. “This is their planet. It is Assisi.” He pressed a button and showed the other computer model. “It even fooled me at first,” he said. “But this isn’t a model of this planet.”

“Where is it then?” Donna asked. Brother Michael was too stunned by the implications of The Doctor’s words to dare speak.

“I’m not sure. I’d have to cross reference with the colonisation programme. But I think… Michael, when were you last on Earth? Ten years ago?”

“Twelve,” he answered. “I had been at the retreat on Mars for some time.”

“Well, I’m taking you for a quick trip home. Don’t worry, I’ll get you back in time to hear Brother Andrew ring the Angelus bell this evening. My TARDIS can do things like that. But first, we’re going to do a bit of investigating of some people whose souls you will have to do some praying for later. Because, if I’m right, they have been very dishonest.”

It took two days in real time to get to the bottom of it all. But The Doctor did, indeed, bring the TARDIS to the gate of the monastery just as the traditional six o’clock Angelus bell sounded. Michael bowed his head in prayer. Donna and The Doctor stood respectfully until he was done, then they went with him to the refectory, where he gathered all of the Brothers to tell them what they had found.

“We have been victims of a terrible fraud,” he said. “Though we have not suffered so badly as some others who were also caught up in it. Assisi was wrongly designated as an unstable planet and colonisation abandoned, because a group of men who had invested heavily in the infrastructure of another planet didn’t want to go bankrupt. They bribed another man to change the designation codes, so that Assisi was thought to be the tectonically unstable planet. Thousands of people went to the other planet, and have been beset by disasters. Many lives were lost only last year in a volcanic eruption.”

Michael paused then. He and the Brothers prayed for the souls of those who died so needlessly.

“The Doctor brought irrefutable evidence of the fraud to the authorities. Arrests were swiftly made. Just punishments will be exacted on those who knowingly placed those souls in danger to fill their own pockets with credits.”

Brother Michael’s face twitched with suppressed anger as he spoke. The Doctor’s face was exactly the same. Donna noted that they shared the same opinion about greed. It was a good job they were both men of peace, or the culprits might have found themselves receiving some even swifter justice than they were getting.

“But, what happens to us?” Brother Andrew asked, on behalf of all the others.

“We continue our work, here,” Brother Michael replied. “We prepare the way for the colonists who will come. The first ships will take another four years to arrive. But by then we shall be more than ready to do the work we came here to do.”

There was a pause. Then men who were used to living a quiet, contemplative life, all cheered as one. Afterwards they said some long prayers of thanksgiving, especially for sending The Doctor to work his miracles among them. The Doctor was still insistent that he didn’t do miracles. But he let it pass.

“Time for us to go,” he said to Donna and she nodded and followed him away. They stepped out of the monastery and crossed the fragrant garden. As they reached the front gate, the bell in the spire rang once again. A joyful peal of celebration.

“They’re ringing it for you,” Donna told The Doctor. He looked up at the spire and smiled before turning and stepping out through the gate to where he left the TARDIS. A few minutes later the bells briefly accompanied the thrumming of the engine as it dematerialised.

|

|

|