The Beta Delta system, as the students of New Canberra High School learnt in their geography lessons, was selected because all but the innermost and outmost planets of the system were suitable for Human habitation with a little terraforming where necessary. Beta Delta I, the innermost planet was never deemed suitable for colonisation, but the huge brown desert was the raw material for the production of much sought after smoked glass.

That much nobody at the school was likely to forget!

Beta Delta II was still a little too close to the sun to be colonised on a wide scale. But the edges of its one huge continent had some very beautifully designed cities and towns and a tourism industry based around water sports and unspoilt beaches. It also had virtually untouched plains that were explored by those who liked a challenge, and mountains from which the freshwater rivers flowed. One of them, named the River Malin, flowed for at least fifty miles along underground channels beneath the Amytal Mountains, and the river and its tributaries had carved out a system of caverns and underground tunnels that tempted the really adventurous.

Chrístõ always considered himself really adventurous. And when the question of a summer vacation trip for his class came up he found that they were enthusiastic about the idea, too. He got the permission slips signed by their parents and planned out a schedule, ordered equipment, booked shuttle flights for the three week trip and made a few slightly more unusual arrangements. Julia, of course, was coming with him. Cordell and Michal had wanted to come, too, but the thought of a twenty mile cross country hike, then a full day walking up a mountain to the entrance to the cave system, and other hardships and feats of endurance luridly described by Chrístõ put them off in favour of Delta Harbour holiday park and the promise of waterslides and unlimited ice cream.

The twenty mile cross country hike was achieved in the first two days, following the course of the river across the plain and into the mountain valleys. On the third they set off at sunrise and trekked up the mountain along natural paths to the plateau where the main cave entrance was. Now, they looked from their elevated position across the Malin Plain as the sun dropped to the horizon. They rested and congratulated themselves on what they had achieved so far.

At sunset, of course, Chrístõ was always reminded of Gallifrey. He sighed as he looked at the red-orange sky on the horizon and the brown-orange tint to the cloud strata caught underneath by the sun’s rays. He shook his head and told himself not to get melancholy. One day he would walk again under a sky that was yellow even at midday and burnt orange at sunset. Until then, he couldn’t let his deep sorrow spoil his enjoyment of other sunsets.

He felt Julia’s hand in his. She was the only one of the group who wasn’t psychic, but she knew him well enough, and recognised that look in his eyes. He put his arm around her shoulders and cherished her nearness, one of the true compensations of his exile.

“Sir… I mean… Chrístõ…” Lara Nuttino, the baby of the group, being three months younger than Julia, called out to him. They were just about getting used to calling him by his name during the holidays. He wondered if they would manage to go back to ‘sir’ when term began again.

“Can we let Humphrey out?” she asked when he responded. “It’s dark enough now, isn’t it?”

“Yes, it is,” he said and went to the oddest piece of baggage that ever travelled by the Beta Delta inter-planetary shuttle system. It was a big, round, padded bag, fully insulated so no harmful light could get inside. Chrístõ had carried it on his back in addition to his ordinary rucksack and waterpack and the jelly wobble movements and the assortment of trills, purrs and very theatrical snores that emanated from it had been a constant source of amusement.

Now it was quite dark enough to let him out. Chrístõ unzipped the bag all around and lifted the top. Humphrey expanded out and enveloped him joyfully before bowling around the camp site, shaking like a dog and greeting all his young friends with his equivalent of a hug.

“Ok, let’s get these tents up,” Chrístõ ordered. “It gets cold very quickly after sundown.”

It wasn’t a difficult job. The flatpacked tents just needed a shake and they expanded out to the required dome shape. Then it was just a matter of pegging them down and tightening the guy ropes. It wasn’t more than fifteen minutes before all of the tents were up and Chrístõ had lit the portable camp fire that actually looked and felt almost like the real thing, apart from the fact that the wood never burnt. For preference, he would have lit a real one, but there weren’t any trees around there to provide firewood.

He knew how to cook camp fire food, too. He managed to think without too much bittersweet feeling, about the times when he had camped on the Gallifreyan plains with his father and made their own supper. But with seventeen people to feed and nowhere they could forage for nutrients like cúl nuts, they had brought ration packs. These worked much like the tents. They were flat foil disks which were twisted and pressed in the middle and they expanded to the size of a dinner plate and began to either heat up or cool, depending on what sort of food it was. Day 3, Supper, turned out to be a chicken casserole that almost tasted like the real thing and a rice pudding with honey flavouring. A third disc pressed open and became a hot mug of cocoa. And when they were done, the plates and cups could be crumpled into light foil balls that they would deposit in a recycling receptacle when they got back to the spaceport.

That was the theory. A group of young people with nascent telepathic skills found other uses for them. Carlo Dennis turned his into an origami aeroplane. He held it in his palm and the Benning twins concentrated hard and made it rise up into the air. They managed to get it to fly around the camp three times and land back on his palm before they had to give up.

“That’s not bad,” Chrístõ told them. “I’m useless at telekinesis. You two just need to practice more.”

“It’s very tiring,” Marle admitted. “Physically tiring. We can’t do it more than once a day.”

“Suck a couple of glucose tablets before and after you do it,” Chrístõ advised. “Then you use the sugar burst rather than your own energy reserves and you don’t leave yourselves so drained. Meanwhile, the stars are out. Let’s make the most of them for the last time before we go down the throat of the Bear. Who can identify the constellations? They’re all in slightly different positions than you’re used to on Beta Delta IV but you should recognise some of them.”

Watching familiar stars in unfamiliar configurations occupied their minds for a while, then they turned to thoughts of tomorrow and studied the maps of the cave systems. They discussed the cave behind them, called the Mouth of the Bear because those with imagination could see it as such. The debate centred on whether the bear was roaring or yawning. All of the girls preferred to think it was a sleepy bear about to settle down to hibernate after one last yawn. The boys were more blood-thirsty, saying it was roaring for its supper. Chrístõ noted that gender divisions of that sort had never quite been eradicated from the Human psyche. The girls were as game for the adventure tomorrow as the boys. But they had a distinct opinion about what sort of imaginary giant bear they wanted to sleep in front of first.

Humphrey didn’t care what sort of bear it was. When Chrístõ put out the fire and they used their torches to find their way to their tents, he happily found himself a place at the back of its mouth to spend the night. Julia went with Lara, Gretta and Glenda to their girl-only tent while Chrístõ was sharing with Laurence Benning and young Carlo. Once he had persuaded Humphrey to stop pretending to snore in a cave that acted as a perfect echo chamber they all got a good night’s sleep.

They rose just before dawn and watched the sun rise as they ate their flat packed breakfast and drank coffee. Then they struck camp and were ready. They said farewell to the sun and entered the echoing gloom of the Bear’s Mouth. Humphrey greeted them with an excited trill and established himself as leader of the expedition.

“He thinks that he’s our official guide,” Julia laughed. “Because he’s a cave creature himself.”

“His cave is about one hundred million light years from here,” Chrístõ answered. “He doesn’t know his way around these caves any better than we do.”

But in fact, Humphrey did seem to know where he was going. Chrístõ plotted their route through the water worn tunnels on a map, but Humphrey led by instinct, chattering away incoherently.

“Are there some of his own kind in these caves, do you think?” Julia asked. “Is that why he is so excited?”

“I don’t think so,” Chrístõ answered. “His kind need the presence of other species to thrive. That’s why they died out on his own planet. The mining stopped and not enough people came exploring the natural caves. The ones in Derbyshire have all the tourists to provide them with the emotional energy they seem to need to survive. But here… the planet was uninhabited for millennia. And even now, cave exploration isn’t yet a big enough hobby to make these caverns busy. I don’t think his sort could be here. But he’s happy with the chance to explore along with us.”

“He wouldn’t get us lost, would he?” Carlo asked.

“Of course not,” Gretta answered. “He’s a really clever… whatever he is.”

“We won’t get lost,” Chrístõ assured her. “If we did, we would just have to find the Malin. It’s down below somewhere, and it runs right through to where it emerges in the open air. We’ll do that eventually. But first we want to explore some of the more interesting caverns.”

“We’re right under the mountains,” Marle said. “I can feel them above us.”

“Can you?” Chrístõ was surprised. “I always can. But I didn’t know you could.”

“I’ve never been in a deep cave before,” she answered. “But now I am… I feel it. It’s a strange feeling. Not oppressive or anything. It should be, shouldn’t it, knowing there is all that weight of earth and rock over us. But reassuring, in a way. We’re safe in the bosom of the mountains.”

“Yes,” Chrístõ agreed. “That’s a good way of thinking of it.” None of the others had the same feeling, though. Of his fifteen Crysalids, Laurence and Marle were not only the eldest, at 17, but the most skilled telepaths. It came easy and natural to them. He couldn’t even take credit for their development. All he had done was provide them with opportunities to use their skills and not be afraid of them.

For two miles according to his interactive map, the tunnel continued, sometimes wide and high, sometimes narrow with jutting out rocks to negotiate. But it was no more arduous than the hike yesterday. The air was good, and it was perfectly dry. The stream that carved the tunnel diverted itself millennia ago. It was on an incline, but not such a steep one that it felt like an uphill climb. They walked steadily and chatted among themselves as they did so.

“The Cathedral cavern is the first of the really spectacular sights on our tour,” Chrístõ said. “And our first serious descent with ropes and harnesses. We’ll have lunch at the bottom. So anyone who chickens out of going down will go hungry.”

That made them laugh, and he felt it ease their anxiety about the prospect of what, for most of them would be their first real abseiling experience.

When they emerged from the tunnel onto a wide ledge halfway up the cavern, they forgot to be nervous about anything for a while. They were too busy being overawed.

“It’s….” The word ‘it’s’ susurrated around the group as they tried to find a suitable adjective.

“It’s fantastic,” Chrístõ settled for. It was as impressive as he had been led to expect when he read about the Malin cave system and decided on it for their summer expedition. It was as big as a good sized church – cathedral was a very slight exaggeration. But for something created purely by nature over thousands of years that was good enough. It had some kind of naturally reflective mineral in the rock walls, quartz or something like it. Their torchlights refracted and reflected off the walls and they could see perfectly well.

It was like an upturned bowl. A glittering roof high above and a flat floor below, with the odd erratic boulder. Unlike most natural caverns Chrístõ had been in, there weren’t many stalactite/stalagmites on the roof and floor, although there was a magnificent example of that sort of accretion along one wall. There, stalactites and stalagmites had long ago joined up to form pillars, and they were so densely packed they formed what speleologists called ‘organ pipes’, all the way up the wall. Chrístõ felt as if there was an etude by Bach playing in his head as he looked at it. He easily imagined organ music filling this great space and swelling in the hearts of all who listened. But nobody had ever thought of doing such a thing here. And if they had, there was a serious problem with getting the instruments to the concert hall.

There were three experienced climbers and abseillers amongst the Chrysalids. The Benning twins and Pieter Stein. Julia had done hill climbing on several different planets with him, but along with most of the others she had only practiced on the school gym climbing wall in the weeks leading up to the trip.

The less experienced put on their safety harnesses and watched as Chrístõ and Pieter hammered the pitons in place to which the static ropes would be attached and fixed the line that they would use to control their descent. Then Laurence and Julia went first. Chrístõ and Pieter watched carefully from the top as Laurence kept pace with Julia. She looked scared at first, but gained confidence and actually looked as if she was enjoying it after a while. Humphrey, of course, drifted down between them, trilling happily. They were all used to him bowling along near the floor, but of course he only did that out of deference to his gravity-challenged friends. To him a hundred foot drop was nothing. When they were at the bottom, he came back up as if on a turbo lift ready for the next two.

Marle went next, along with Carlo. Carlo was determined not to look scared, because he was a boy, after all. Those gender stereotypes again. But sharing a cavern with sixteen other telepaths it was difficult to hide how he really felt. For the first twenty feet they were all aware of his stomach churning fear, before he started to realise he was the one in control of his own destiny and slowly started to feel like this was an adventure not a torture.

Two experienced people were at the bottom now, and two at the top. They were ready to guide the inexperienced ones.

“It’s just like the school wall, only higher,” Chrístõ assured Rudie and Noreen as they got ready to go. “It isn’t much different. Forty feet or a hundred. It just takes a bit longer.”

“It takes less time if you fall,” Rudie observed. “A falling body gets faster the longer it descends. Newton’s laws…”

“Chrístõ’s laws say we’re not going to worry about that today,” he answered. “Besides, Humphrey is going to be with you all the way.”

“Humphrey can’t catch us if we fall,” Noreen pointed out. “Can he?”

He had to concede that she was right. Humphrey would be as useful as a cloud in that case. But he gave Noreen and Rudie one of his ‘hugs’ and that gave them the confidence to make the first step off the edge. He hung in the air just below them as they descended, at first painfully slowly, and then with growing confidence in themselves and the fact that every foot lower meant less likelihood of broken bones if they did fall.

“It’s easy enough,” Geoffrey Walker said as he got ready. “I’m not scared. I was the fastest when we practiced.”

“You’ll be the fastest today, too, if you go like that,” Pieter told him. “Your harness is fastened all wrong. It will come apart as soon as you put your weight on it.”

Geoffrey’s pride took a serious fall, which was far better than his body. Chrístõ smiled as he watched Pieter sort him out and helped Glenda Ross clip the descender rope to her harness safely.

“I don’t want you going down fast,” he told Geoffrey. “Glenda isn’t so sure of herself and she needs you to keep pace with her. This trip isn’t about being first. It’s about being safe and it’s about being a team. You look after Glenda. And I’ll see you both at the bottom, soon.”

He was pleased to see that Geoffrey took both his chastisement and his responsibility equally to heart and descended carefully, talking to Glenda, reassuring her that she was going to be all right. Archie Joyce and Vern Koetting both needed their harnesses re-adjusting first, but they managed the descent without any trouble. Lara Nuttino and Damon Lee both took some coaxing before they would step off the edge, but Chrístõ and Pieter both smiled as they felt the two novices swap fear for elation.

“I think those two should join the climbing club I’m with,” Pieter said. “They’re naturals.”

“I might join that, too,” Chrístõ told him. “Marianna always says I don’t get enough fresh air.”

Angela and Gretta started off all right, but Gretta panicked about half way and froze. Angela waited next to her. So did Humphrey, who enfolded her in his most reassuring hug, but she was afraid to move.

Chrístõ watched her and remembered the first time he climbed Mount Lœng, when he had thought he couldn’t move up or down without falling. He had so wanted a helping hand, but he didn’t get one, only Maestro, taunting him for being weak, giving him the spur to haul himself up by his own effort.

“Was that really you?” Gretta asked. He smiled. He forgot sometimes that his Chrysalids could read his thoughts easily unless he hid them. “Were you really that scared?”

“Yes, I was,” he answered. “I felt just like you do, now. I felt small and weak and hopeless. But I wasn’t. And you aren’t, either. I’m not going to say mean things about your mum to get you to move. Anyway, since I’m up here and you want to go down it wouldn’t help, would it. But the lesson I learnt that day – if I’d had to have help, I really would have been weak and hopeless. I did it by myself and proved I could overcome my fear. And so can you. Just let a little of the line out, drop a few more feet and then rest again. You’re the one in control. You’re the one who’s going to do it. Angela is beside you, and Pieter and I are up here. But we’re not going to help you. You’re going to do it for yourself. And you’ll be glad you did.”

Gretta did as he said. She let out a few inches of the descender rope and dropped just a tiny bit before stopping. Then she let a little more, a foot at a time. Angela matched her. Humphrey crooned encouragingly and hovered beneath her, so that she couldn’t see just how far down the floor was. She let out three feet this time and dropped in a safe, controlled way. Chrístõ and Pieter both felt her confidence rising mercurially as she realised she could decide how far and how fast. By the time she was close enough to the ground for Laurence to reach out and help her she didn’t need his help.

“I can’t do it,” said a very small voice and Pieter and Chrístõ looked at the last remaining novice. Malcolm Keogh flattened himself against the rock wall, as far from the edge as possible. He had done the practice with the others. A team of wild horses wouldn’t have kept him from coming on the trip. But now it came to the crunch, he was terrified.

“We should have sent him down with Marle or Laurence at the start,” Chrístõ said. “Then it would have been over and done with for him. He’s had too much waiting time to get scared.”

“If we force him, it will only make it worse,” Pieter told him. “He’s really not cut out for this. It happens. Some people just can’t.”

“I agree,” Chrístõ said. “I was thinking the two of us would be able to do a Space Marine fast descent – a bit of expert showing off – once the others were down. But that’s not going to look so clever now.”

“We should use this as an opportunity to demonstrate emergency procedure,” Pieter told him. “Malcolm, good news. You don’t have to do anything except enjoy the ride.”

“I’ll take him,” Chrístõ said. “You pace me.”

The possibility of somebody being injured had been accounted for. They had the right kind of harness and clips to make a tandem descent. Malcolm was secured, piggy back on Chrístõ as he came down much slower than he would have liked to have done it. Pieter descended alongside him. Malcolm kept his eyes shut and closed off his thoughts. He didn’t want anyone to know how scared he was.

“Open your eyes,” Chrístõ told him finally. “Look up and see how far we’ve come. And keep on holding tight for another twenty seconds.”

They were down. Malcolm touched solid ground and sighed with relief. Pieter and Laurence came to unclip him and Chrístõ turned to look at them all.

“You all did great,” he told them. “Malcolm, I know you’re good at remote telekinesis. You and Laurence undo the guide ropes and bring them down so we can use them again.”

Malcolm nodded and closed his eyes again, this time to visualise the pitons hammered into the hard rock floor of the ledge. He focussed his mind on slowly undoing the knot that Chrístõ had tied very carefully, so that the rope would not come unfastened accidentally.

Laurence did the same, but his rope got stuck.

“There’s nothing wrong with your telekinesis,” Chrístõ assured him. “Pieter used a double figure of eight loop to secure that line. I only used a single one. Malcolm, can you help him out?”

Malcolm was more than happy to help. Slowly they completed the task and controlled the descent of the loose ropes so that they landed pre-coiled and ready to be packed again. Marle gave both of them sucrose sweets to help them combat the dizziness that comes after so much mental effort before they gathered together to open up Day 4 – Lunch – Shepherd’s Pie - with the satisfaction of having achieved something they would remember for a long time.

As they rested after eating their food and drank their flat-packed coffee Chrístõ responded to a question from Glenda, and told them all about how he first found Humphrey in a cave system on another planet a long way from the Beta Delta system, and how he had saved his life more than once.

“Isn’t it boring being a teacher after doing that sort of stuff?” Archie asked.

“It’s restful,” he answered. “I like being a teacher. I like teaching you lot.”

“You won’t want to be our teacher when the war is over and you can go home, though,” Glenda said.

Until she asked that question he had not really thought about it. Marle and Laurence would only be his pupils for another eight months or so. They would be eighteen and ready for those exams that would see them off to their choice of university and glittering careers after that. The others would have as much as three more years before they could take the same exams. If the war lasted that long, what would there be left to return to? Who would be left? His planet would be changed beyond recognition. But here were people who needed him, who he could help in so very many ways. And it was true. He liked being a teacher, being their teacher. He certainly wouldn’t just walk away from them.

“When the war is over, I think I will be needed on Gallifrey,” he answered. “But I won’t just abandon you all. I promise.”

That satisfied them. It satisfied him. He would fulfil his duty to them all one way or another. But that was in the future.

For now they had an adventure together. When they were rested they set off again. They crossed the Cathedral Cavern and entered a new tunnel. This one went downhill quite steeply for a good mile before levelling out. But when it did, it started to get very much narrower and the roof lower so that soon even the shortest of the students were stooping and there were regular clunking noises followed by ‘oof’ sounds when they forgot and their caving helmets hit against the roof.

Then it became no more than a crawl space. Chrístõ looked at his map and confirmed that it was the right way. They just had to manage.

“Oh, I don’t like the look of that,” Lara complained. “What if somebody gets stuck?”

“It’s not as bad as it seems,” Chrístõ assured her. “It’s only about twenty yards then it widens out again.”

Lara didn’t look convinced. And she wasn’t alone. Vern and Rudie both looked worried.

“All right,” he said. “We have to do this, just like we had to do the cliff. So the ones who are most scared go in front. Then they get out of it first. Humphrey will lead you. So who really does feel bad about this?”

He was surprised when Julia put her hand up.

“You’re not scared of anything,” he told her.

“I don’t like little tunnels,” she said. “I sometimes used to hide in the air vents on the ship. And it was scary.”

“Oh, all right, sweetheart,” he said and hugged her briefly. “But you got through that. And you’ll get through this. I promise you.” He hugged Lara, too. She looked as if she needed it. “Come on. It will be all right.”

Humphrey added his opinion on the matter, an encouraging purr and trill that stirred the hearts of the most timid as he hovered by the dark hole they had to negotiate. Julia knelt and pushed her way in. Her voice came back muffled, and she was clearly not happy, but the light of her helmet lamp at least made it look less ominous. Vern followed her, then Lara and Rudie. Chrístõ counted the rest of them in before he brought up the rear.

It wouldn’t have been so bad if it was just their own slim bodies going along. Julia with her gymnastic agility would have had no trouble. But they all had rucksacks full of equipment to manage as well. The worst hold-ups occurred when straps caught on rough parts of the roof and had to be untangled. Nobody was especially happy about this bit, even those who weren’t particularly scared by it.

“Hey,” Chrístõ said. “Did you hear the one about the vegetables in the soup canning factory? They complained that there wasn’t mush room in the tins.”

Up ahead of him three or four of his students heard the joke and laughed. They passed it on telepathically up the line. Then a moment or two later Chrístõ had a message relayed to him.

“Julia says the one about the sardines is funnier.” But by then they were all making jokes and the confined space and the strange patterns of moving light were not bothering them as much as before. And it didn’t seem as long as it might before they started to get excited telepathic messages from those in front. They were out into the bigger tunnel again.

“Are we all here?” Chrístõ asked when he finally stood upright and stretched his spine gratefully. Julia hugged him and Humphrey hovered about smugly, having led them through that tricky spot.

“Shall we go on then?” Chrístõ asked once he had confirmed with a headcount that everyone was present and correct. “According to the map we have a new cavern in about two hundred yards.”

The two hundred yards were slightly downhill and the tunnel roof remained comfortably above their heads. The joking atmosphere continued and laughter echoed around the tunnel walls.

“Wait?” Marle called out. “Can you hear something?” Immediately they all stopped and the echoes of laughter died away. They heard a different sound. One they had missed because of their own noises.

“Water?”

“Oh no,” Carlo moaned. “I can’t swim.”

“You don’t have to swim.” Chrístõ assured him. “Just prepare to be amazed.”

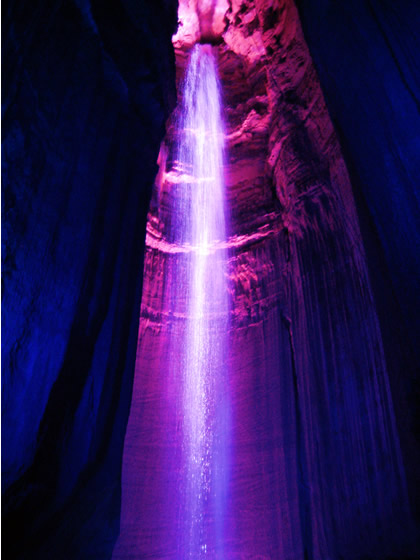

He knew what they were heading towards. He had read about it and seen pictures when he organised the trip.

But even he was stunned when they came out into what was marked on the map as Angel Falls cavern.

“Angel

Falls after the highest waterfall on Earth,” Archie Joyce noted.

“I don’t think this is really as high, but it’s really

something.”

“Angel

Falls after the highest waterfall on Earth,” Archie Joyce noted.

“I don’t think this is really as high, but it’s really

something.”

“It could be higher,” Angela Wright contradicted him. This is only a part of it.”

They all stepped as close as they dared, the icy cold spray dampening their faces in a refreshing way. They could just about see where the waterfall tipped over the edge of the cliff near the top of the cavern, through a tunnel just like the ones they had walked along, only the river still ran through this one. They followed it down and looked where it fell through a chasm in the rock floor. If they listened carefully it was possible to hear the echo of the water falling much further down to another cavern somewhere beneath their feet.

The sound was deafening. Everyone except Julia talked telepathically. She hugged close to Chrístõ and said nothing. She had nothing to say. She was too busy watching this beautiful natural phenomena.

“It goes down to the Malin river,” Chrístõ said out loud for her and telepathically. “It’s one of its tributaries. The river is directly beneath us now in the very lowest cavern, which is our last big one before we have tea and think about making camp.”

The students were reluctant to move on. They all found the sight of that raging water so fascinating.

“It’s like being outdoors,” Malcolm explained. “It makes the air so cool and fresh. Not like the other cavern where it felt deep underground.”

“We’re deeper underground here than we were there,” Glenda pointed out to him. “But I sort of know what you mean. It’s too noisy to stay here long, though. We should get on.”

The way down, not surprisingly, was another tunnel. This one fell very steeply, but in a series of wide steps, all naturally formed by the action of the water that had once run through this tunnel. They all tried to imagine what it was like when these steps had been a series of white water cataracts filling the air with the sound of rushing water. It would have been even louder in the enclosed space than the great fall they had just been looking at.

“What happened to the water?” Julia asked as she walked beside Chrístõ, glad of a path wide enough to do so. “There must have been such a lot of it once.”

“The stream must have found a different course. Perhaps there was a landslide. The cavern back there was probably formed that way. That’s why the waterfall. The river bed disappeared and it fell down the cliff instead.”

“Landslide?” Nobody liked the sound of that word.

“Don’t fancy that,” Carlo said. “What if the river decided to come back down here?”

“It’s not likely to happen today,” Chrístõ assured him. “There hasn’t been any major slips here for at least…”

Later, when he was able to joke about it, Chrístõ admitted that it was asking for trouble, walking inside a mountain that was like a Swiss cheese, and talking about how it had not had a landslide for so many years. It was the same particular paragraph of Murphy’s Law that always tripped him up every time he said to anyone that his TARDIS was on course and everything was working fine.

He really should have known better.

It started with a rumble and a change in the sound of the waterfall that still echoed through the tunnel even though they had gone a good mile or so already. Then they felt a tremor and then the air displacement and the rumble of a roof fall somewhere ahead of them.

Vern and Lara screamed the loudest, the two who had been most scared of the narrow passage earlier. The others were upset, too, though. Even Laurence and Pieter, the oldest boys, who always tried to maintain a certain dignity, looked pale in the torchlight. He reached out and felt Julia’s trembling hand.

“Is everyone here?” he called out as he turned about and counted heads. They were all there, and nobody was hurt. Humphrey was buzzing around noisily, hugging everyone. “All right, let’s see how bad it is up ahead. Pieter, Laurence, can you run back and see if we can get back the way we came, just in case.”

He would have preferred it if the others hadn’t followed him, but Julia had no intention of leaving his side and the rest of the students felt much the same way. They came with him to the point where the roof had caved in, blocking the tunnel. He closed his eyes and concentrated. He felt the mass of debris and guessed that it was about four or five feet thick. Beyond it was air again, a bit dusty, but still a tunnel.

“Maybe some of us could get through,” Julia suggested. “The smallest… there’s gaps… We could try.”

Lara, Vern and Carlo, the smallest of them, all fourteen, said they would be prepared to try as well.

“But you were the ones who were scared of the tight crawl,” Chrístõ pointed out.

“Yes,” Julia answered him for them all. “But this isn’t as far, and beyond there, according to the map, it’s only a little way down to the cavern underneath, where the river is.”

“Yes, but it might not be the only fall, and it’s all unstable. No, I won’t let you risk it. Besides, the rest of us can’t get through and I don’t want to split us up. Let’s get back to the Angel Falls cavern. We can sit and have an energy bar and a drink and think about things.”

Back there, though, was more bad news. The passage they had come down was completely blocked even before they got to the tight bit. Pieter gave his opinion that they shouldn’t even try to force a way through.

“Then we’re trapped?” The dismaying thought went around the group.

“There is another option,” Laurence said. And he pointed out something that had not occurred to any of them until now, though they should have seen it right away. The cavern no longer echoed to the roar of the waterfall. Chrístõ looked up at the tunnel it ran through before plunging down the cliff. It was blocked as the lower tunnels were. He and Laurence stepped carefully towards the chasm. Without the wall of water passing through it they could see how wide and deep it was, but not exactly where it went. They could hear the river somewhere below, though, and they could make a guess.

“A guess isn’t good enough. I need to take a look,” Chrístõ said. He pulled the piton gun from his pocket and fired one of the strong steel pegs into the rock floor by the edge. Pieter fastened one of his double figure of eight knots. Chrístõ lowered himself down carefully. There was at least twenty feet of solid rock, very solid, but slippery with the water that had fallen down it constantly for centuries. But then he came out into the top of a wide cavern. It was a good eighty feet, he estimated, not to the floor of the cavern, but to the Malin river as it flowed underground. He looked at it carefully in his torchlight then hurried back up to report to the others.

“It can be done,” he said as he explained what he had seen. “It’s harder than abseiling down a cliff face, but it can be done. We just need a couple of experienced people to go down first and swing across. Then they can fix pitons and make a static line that everyone else can come down.”

The three experienced climbers nodded in understanding.

“We have to work fast,” he said. “Fix two more pitons for the top of the static lines. We’ll get three down at a time. Marle, you go first and take the piton gun. Lara and Damon, you go with her. You both did well on your first descent and you can help her. Then Laurence, you take Malcolm in tandem and Gretta and Angela will go with you. Then the rest in turn. Malcolm, I know you’re not happy about this. But we don’t have any choice. We have to get everyone down quickly.”

They worked quickly and efficiently. The first three took a deep breath each and dropped over the edge. Chrístõ felt their thoughts. The slippery wall was hard but they knew what to do. When they dropped into clear air, though, they were less happy, and swinging over to the river bank was heart-stopping. But he sighed with relief when he heard their telepathic messages to tell him they were all safe. He waited until they told him the lines were in place and got ready to send the next four down, Malcolm screwing his eyes tight shut.

“I wish I could, too,” Laurence joked as he went down over the edge. Chrístõ kept his eye on the piton that was supporting their double weight. But Pieter did strong knots and it was all right. Marle, Lara and Damon were ready at the bottom to help them and soon they were safely on the riverbank.

But the ropes weren’t the only things under strain. Chrístõ looked up. There was a spout of water forcing through the blocked tunnel. The river that fell down this cliff was a fast one. A lot of pressure must be building up. Sooner or later it would go, and anyone who was still up here would have no chance of getting through.

“Carlo, Rudie, Julia,” he said. “You three next.”

“No,” Carlo said. “I can’t. I told you. I can’t swim. I can’t…. I really can’t do it. Not above water.”

“But you won’t even touch the water,” Chrístõ promised him. Carlo shook his head. He couldn’t bring himself to do it. And they didn’t have time to coax him down gently.

“I’ll bring you down on tandem,” Pieter said to him. “But that means you will have to wait. Chrístõ and I are going to be the last to go down.”

“Ok, Rudie, Julia, Noreen,” Chrístõ decided. “Go on.”

Julia looked as if she wished she could go tandem, too. She didn’t want to leave Chrístõ up here. But she knew better than to ask. She hugged him and then let him connect her descending rope. She dropped into the wet chasm and he watched, hearts pounding, until he heard Marle’s reassuring message in his head. They were safe.

“Geoff and Glenda,” he said. He and Pieter checked their harnesses. This time both had it right, and Geoffrey wasn’t pretending that it was easy. They descended steadily. As they did so, a spout of water forced itself through the rubble and crashed down into the chasm. Their helmets protected their heads from the small rocks and debris but they shouted in shock as the water drenched them. It made their descent that much harder and the need to hurry much more imperative.

“Slowly,” Chrístõ warned them, even so. “Don’t rush and slip. You’ll be all right.” He said the same to the last two, Archie and Vern. They had it worst, because now it was a steady fall of water that they had to climb down through.

“Pieter,” Carlo said in a small, scared but determined voice. “I think… I’m… if you have to carry me you’ll be slower?”

“Yes, but there’s no other way.”

“Yes, there is. I can try to do it myself. I am scared, but I can try. As long as you both stay with me.”

“Good lad,” Chrístõ told him. Pieter, too, praised his courage. Humphrey hugged him as Chrístõ fixed his harness and made him ready. The three of them stepped off the edge together. Humphrey hovered overhead. The two experienced climbers kept pace with Carlo, who managed all right for the length of the wall, but once they were in the open he froze unhappily.

“Carlo, don’t stop.” They all felt Gretta’s voice as she called out telepathically. “Like Chrístõ told me when I was scared. You have to do it for yourself or you’ll never do anything. And you can do it. You can.”

It worked. Carlo inched his way down the rope until he was a few feet above the river that terrified him so much. Chrístõ and Pieter kept clear until Marle and Laurence caught his belay line and hauled him to safety.

“Oh @#£$%%,” Chrístõ swore as they heard the crash they had expected for several minutes. The river had finally built up enough pressure to push the blockage ahead of itself and break free. Rocks and debris and gallons of water were plunging down as he and Pieter clung to their ropes beneath it all.

Then they both felt a different force above them. They dared to look up and saw the deadly torrent held back. It was the others, focussing all their psychic powers on it. He had taught them to do it using a dripping tap in the classroom. But this was so much more effort. He didn’t waste any time thinking about it, though. He and Pieter slid quickly down their ropes, reaching to detach themselves from the descender as soon as they were over the bank. Laurence and Marle reached to help them and they stood up on dry, solid land as their friends let the forcefield collapse. Humphrey bowled through them making a frightened noise, even though nothing could actually harm him.

“Move, run,” Chrístõ told them. They were all physically exhausted by the effort, but self preservation spurred them on. They ran towards the back wall of the cavern and pressed themselves against it. They watched as the river roiled up around the debris that landed in it and gradually calmed as the waterfall found its normal level once again.

“Wow!” was the collective remark as their heartbeats returned to normal and they found a voice to describe their near miss. No-one was hurt. They had been scared, but it was all over now and they could laugh and hug each other and be thankful that they had made it. Humphrey caught their feelings and gave them back tenfold in his enthusiastic multiple hugs.

“What now?” Pieter asked.

“Well,” Chrístõ answered. “The original plan was to go upstream from here through a whole series of fantastic caverns, over the next week or more. But I think now we should go downriver instead. That’s still a three day hike, so the adventure isn’t over yet. But once we get out of the mountain it’s only a short riverside walk to a mountain rescue centre that will have videophones. We can all let our loved ones know we were in absolutely no danger and positively didn’t do any dangerous stunts involving chasms and long drops over raging rivers.”

He looked around and smiled. One more secret he and the Chrysalids would share.

In fact, near midday of the second day of their trek along the underground Malin river, as they were finishing a meal – Day six, Lunch, Saffron Chicken and cous-cous with roast vegetables followed by hot fudge pudding, they saw lights coming up river and the sound of a motor launch. The Mountain Rescue volunteers were surprised to find that the group of schoolchildren they were searching for didn’t even consider themselves lost. They accepted the offer of a boat ride downriver, all the same. Humphrey settled himself into his carrier and wobbled and snored and did impressions of the waterfall and the motorboat engine as the others greeted the sunlight happily.

“There’s a danger of more landslides,” Chrístõ told them all when they were settled at the mountain rescue station. “So I think that ends our caving adventure holiday. But I’m thinking we might head for the coast and spend the remaining time learning to surf – or in your case, Carlo, learning to swim, plus a bit of sunbathing and unlimited ice cream. It won’t be as much fun for Humphrey, but we can probably arrange some after dark beach barbecues for him to join in with.”

The idea met with general approval, apart from some indignant noises coming from the wobbling backpack.

|

|

|