They looked at the oddest piece of architecture any of them had ever seen.

The oddest TWO pieces of architecture. One was a tower that put Chrístõ

in mind of the infamous leaning tower of Pisa on Earth, except that the

architect here had got it right and it was perfectly perpendicular and

already twice as tall as the Earth monument. Around each floor of the

tower names were engraved, commemorating the dead of a bitter war fought

over this planet fifty years before, and inside each level was dedicated

to art, music, literature, science; a library, art gallery, conservatory,

planetarium open to the public and artists studios, writing rooms, music

rooms and laboratories. The floors were reached, not by internal stairways

or lifts, but by a wide staircase that wound around the outside of the

tower.

They looked at the oddest piece of architecture any of them had ever seen.

The oddest TWO pieces of architecture. One was a tower that put Chrístõ

in mind of the infamous leaning tower of Pisa on Earth, except that the

architect here had got it right and it was perfectly perpendicular and

already twice as tall as the Earth monument. Around each floor of the

tower names were engraved, commemorating the dead of a bitter war fought

over this planet fifty years before, and inside each level was dedicated

to art, music, literature, science; a library, art gallery, conservatory,

planetarium open to the public and artists studios, writing rooms, music

rooms and laboratories. The floors were reached, not by internal stairways

or lifts, but by a wide staircase that wound around the outside of the

tower.

It was a fine, beautiful thing.

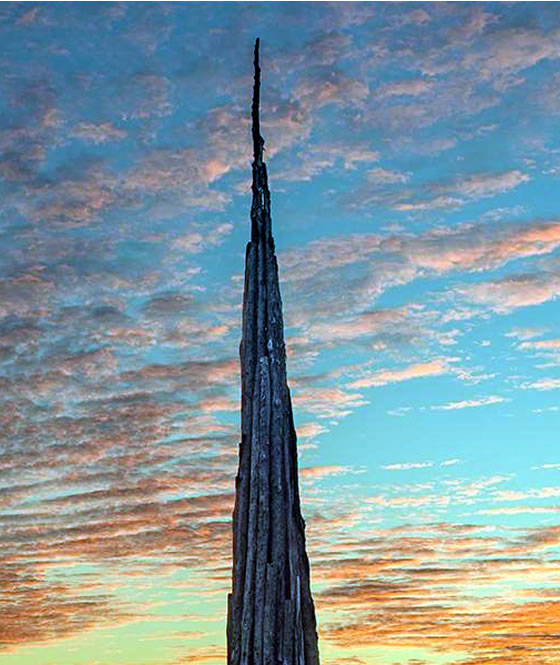

And it was unfinished. There was meant to be a spire on top of it, rising to at least a third of the height again.

The spire was on the other side of a wide plaza. It had been built from the ground up. It tapered to a point which seemed to be made of crystal glass, shining in the sunshine. The spire was also decorated with the names of the dead, and it was used as a temple dedicated to the twin gods, Ubaz and Ipotir from which the planet, Ubatir, was named.

The tower represented reason and science and progress, said one section of the Ubatir population. And as such superstition and blind adherence to the idea of impotent and unseen gods had no place.

Another section of the population believed that art and science, literature and music were nothing without faith and believed the spire must go on top of the tower to symbolise religion’s superiority over all life on Ubatir.

Chrístõ thought it was the silliest argument since the one about which end of a boiled egg to slice. His companions had never heard that story but when he explained it to them they agreed.

“I’m just glad it isn’t OUR problem,” Cam said. “We have way more important issues at the Conference.”

“I don’t know,” Kohb argued. “Silly as it is, it IS a cause of dissension. This is a divided people, and sooner or later it will lead to conflict of a more serious sort. It ought to be addressed.”

“Ubatir is the HOST planet, not the subject of the conference,” Chrístõ pointed out.

But he didn’t tell his friends one thing.

Ubatir, host to the Intergalactic Economic Federation Conference, was listed in the presets of his TARDIS databank.

Which meant there WAS something the Time Lords thought he ought to deal with.

“Your Excellencies, sir…” The little man called Dreb who had been assigned as their escort on their tour of the city called to them. Cam was the only one who responded automatically. He was used to being addressed as Excellency. Chrístõ still thought that was his father’s title and Kohb was utterly unaccustomed to being addressed as ‘sir’.

“It is time for the procession. If you would take your places in the VIP box.”

They were escorted to the place where a very sturdy wooden stand had been erected with seats for those who were important enough to have a seat. The general population of Ubatir stood patiently along the route that the procession would take.

“I am not at all happy about attending this ceremony,” complained one of the other diplomats, the representative of Rabr Acer in the Gamma Quadrant. “I am Orthodox Rabrinazian. It is forbidden to acknowledge any other deity but Rabrina.”

“You are a diplomat,” Cam reminded him. “We all are. We have to put aside our personal feelings and respect the religious and cultural customs of our hosts.”

“What god do you worship on your planets?” the Rabrinazian Consul asked him. “On… Gallifrey or Haollstrom.”

“WE don’t,” Chrístõ answered. “We acknowledge The Lord Rassilon as the Creator of the Time Lord race. But we don’t worship him. He was not a god. He was just the first and greatest Time Lord of all.”

He thought he ought to leave out the fact that Gallifrey had several dominion planets where Time Lords were thought to be gods. That wasn’t something that went down well in any conversation.

“We have no religion on Haollstrom, either,” Cam added. “But of course, as an Ambassador for my people I must be aware of local customs. The Procession of the Gods is quite beautiful. The sarcophagi containing the remains of the twin gods are brought through the streets of the city in a parade. They have music and singing as they parade. And the people throw flowers. It seems quite charming.”

Chrístõ looked at the two halves of what was supposed to be the one tower. This ‘charming’ religion was at the centre of that controversy. There was more to it than that.

A fanfare indicated the beginning of the parade, and it was, indeed, a herald with a long trumpet that walked in front, followed by a group of children in white robes holding up banners that proclaimed in the local language, a variant of cuniform, that Ubaz and Ipotir were ‘Good’, that they were the ‘Ever-living Gods’, and other such declarations.

“They are the acolytes,” Dreb explained to them. “Chosen from among the children of Ubatir for the great honour of serving Ubaz and Ipotir. They receive the best education within the monastery and in course of time they become the priests and priestesses of the temple.”

“They seem young for such responsibility,” Chrístõ noted. “And to be taken away from their parents.”

“It is an honour for them,” Dreb assured him. And they LOOKED as if they were honoured, it had to be said. They held their banners proudly and smiled as they walked in procession.

Behind them was a marching band playing a stirring tune, and behind them a choir singing the words of a hymn of praise to Ubaz and Ipotir along the lines already suggested by the banners. Ubaz and Ipotir were the wise, just and the ever living gods.

“Ever living?” Cam queried as a long crocodile of priests and priestesses and cardinals and bishops paraded by, dressed in deep purple and silver for the lower ranks and gold and scarlet robes for the higher. Behind them were the objects of the procession. Two glass sarcophagi were mounted on biers of silver and gold, in turn placed on silk hung beds upon two flatbed wagons covered in silk and gilding and festooned with flowers. They were pulled by six white horses each and flanked by more priests and priestesses who walked either side.

“They look dead enough to me,” Kohb added as they viewed the two dried and mummified bodies within the sarcophagi.

“Those are just the corporeal bodies,” Dreb explained. “But the spirits of Ubaz and Ipotir live on, revealing themselves at the time of manifestation and giving us their wisdom to live by. The time of manifestation is now. You will be witnesses to it. You are honoured, indeed.”

“For real?” Chrístõ asked, surprised, and aware that at least twice in his life he had encountered fraudulent ‘gods’ who used the people who worshipped them disgracefully.

“I don’t understand,” Dreb answered him. “They are the true gods of Ubatir. How could they be anything else but ‘real’?”

Chrístõ realised his comment had sounded disrespectful and apologised humbly.

The procession had passed the VIP stand now, though it would continue around the streets so that as many of the ordinary citizens could see it as possible. Meanwhile the VIPs were escorted to the Spire Temple and shown to their seats before the public were allowed in – those with tickets allocated by lottery. The rest would gather outside and listen to the ceremony by the public address system.

“It really IS beautiful,” Cam said as he looked around. And nobody could disagree with that analysis. It was not elaborately decorated. The designers had gone for a simple style within the temple. It was not circular, but sixteen sided – a hexadecagon. Every other side was cream-coloured plaster with bas-relief carvings of religious symbols. The alternate walls had stained glass windows inset, long and thin, tapering like the spire itself. The twin suns of Ubatir, named, of course, for the twin gods, Ubaz and Ipotir, rose and set opposite each other, east and west, passing close by each other at the zenith, and seeming to become one huge sun. At this time, in the late morning, the sunlight lit all of the windows and the inside of the temple was bathed in warm coloured light. It was all the decoration the temple needed. Seats all around and a simple altar in the middle of the floor completed the scene.

“Beautiful,” Chrístõ agreed. “And yet…”

And yet, nothing, he told himself firmly. He was even worse at precognition than he was at telekinesis. All he had to go on was the fact that the planet was in his list of presets and that almost certainly meant there was a problem with it.

But it didn’t mean there was anything wrong or sinister here in the temple.

He made himself relax and enjoy what was only going to be a very beautiful ceremony.

The procession had made its tour of the city and the fanfare was sounded inside the temple, the sound reverberating richly around the hexadecagon. The children and the priests and priestesses, the band and the choir all filed into the places reserved for them, and with as much ceremony as could be mustered the two sarcophagi were brought to their places of honour either side of the altar.

The ceremony began with music and hymn singing followed by long acts of devotion towards the sarcophagi. It was not unlike any religious ceremony the universe over. It seemed to be timed to culminate at noon-time when the two suns were at their zenith. Chrístõ looked up into the high, tapering roof of the spire. He looked at the inside of the crystal glass pinnacle. The sun at its height would shine right down in a beam of light. He shielded his eyes and watched in fascination as the suns came into position. The crystal focussed the sunlight into a beam like a white laser that came straight down onto the altar and the two sarcophagi either side of it.

And then something incredible happened. With their Gallifreyan eyesight Chrístõ and Kohb were probably the only people who could see it clearly. The others were dazzled by the light.

The sarcophagi were glowing as if the focussed sunlight was being absorbed into them. And inside the glass cases the two blackened, mummified bodies were changing. They were no longer black and stiff. The flesh was growing back clean and fresh. The features on the faces were becoming those of living men.

“It’s not possible,” Kohb murmured.

“No, it’s not,” Chrístõ confirmed. “Nobody, nothing, can bring the dead back to life.”

But it didn’t look like any obvious trick. It WASN’T a transmat beam. It wasn’t anything like the regeneration that he had seen the rogue Time Lord Oakdaene do on Ryemym Ceti. It wasn’t a hologram such as those who had pretended to be the Egyptian gods at Abu Simbel had used.

If it WAS a trick, he didn’t know how it was done.

The beam lost its intensity as the suns moved from their zenith. As it did, the figures in the sarcophagi moved. They pushed open the lids and rose up, their arms outstretched, their robes billowing around their bodies as they hung in the air for a few seconds before gently floating to the ground.

The people were silent. Many of them were already on their knees. Almost all of the rest followed suit until all but the VIP guests, the diplomats from other worlds, were kneeling, waiting for one or both of the two apparitions to speak.

“We are Ubaz and Ipotir, your gods,” the two said together, their voices harmonising. “We bring blessings upon the people of Ubatir, but we must speak also of the great abomination that goes unheeded. This must end.”

The high priest who had conducted the ceremony thus far prostrated himself before them and then knelt up.

“What…. abomination, Lords?” he asked.

“You do nothing about the continued refusal of the men of science to allow our sacred temple to be mounted upon the great tower.”

“Lords…” the high priest began, but there seemed nothing he could answer that accusation with. After all the men and women of religion HAD failed to get the spire on top of the tower.

“THAT, at least is a problem that can be rectified,” the two gods declared. And everyone felt it. The sense of movement. People clutched each other fearfully. But they did not dare raise their voices. Even when the whole temple shuddered violently and many of them fell over they said nothing.

“Go, now,” the gods said. “Spread the word of our power.” And they pointed. At once the temple doors opened wide. The people nearest to it obeyed the command immediately and ran out. They tried to run back in again, shouting something but there were others behind them and they were swept along.

“Go!” the gods repeated. “All but the High Priest. He will remain as our counsellor. He will hear the rest of our commands and bring them to the people in the fullness of time. We will have offerings of food and wine brought for the sustenance of our corporeal bodies. We, your ever-living gods command it.”

The people went. The bands and hymn singers, banner carriers all did as they were told. Some of them had presence of mind to take charge of the children. The delegates from other planets made their way out of the temple, too. Kohb held Cam’s hand tightly as they joined the throng. Chrístõ envied them. He wished he had a hand to hold. But the only one available was the Ambassador representing the planetary state of Fahot, a seven foot man who was very nearly half as wide again, with a skin the texture of concrete. He had already suffered pins and needles for ten minutes after shaking hands with him at the informal diplomatic cocktail party the night before. Chrístõ stood back to let him go out through the door first, his bulk blocking the sunlight momentarily. Then he and his friends stepped out.

“What!” Cam exclaimed as they stepped, not onto the wide plaza, but onto a narrow balcony running around the top of the Great Tower. Chrístõ went to the parapet and looked down. The plaza was full of people looking up in amazement. And he was not at all surprised at that. Before he began to make his way down the winding staircase to the ground he looked up at the Spire, now sitting atop the Tower where it had been intended to go.

“It’s a miracle,” people were saying. “A demonstration of the great might and power of Ubaz and Ubatir.”

And Chrístõ, for whom science was his first passion, who had always thought there was a scientific explanation for everything, could not dispute that. Because he could not find any scientific explanation for what had happened.

When he reached the plaza he moved through the crowds as quickly as he could, until he reached the place where the spire had stood until half an hour ago. He had his sonic screwdriver in his hand and he scanned the area with it. There were no traces of any form of transmat or teleport technology. There was none of the residual energy that even a dematerialising TARDIS left behind for a brief time. And if it had been telekinesis he would be suffering the mother of all headaches right now standing in a place where THAT much telepathic energy had been used.

“It looks amazing,” Cam said.

“Impressive,” Kohb added. “There is no obvious join. It is as if the two parts of the structure were always one.”

“You used to do magic tricks,” Chrístõ said to him. “Did you ever do one like that?”

“Not for real,” Kohb answered. “My ‘magic’ was mostly clever sleight of hand. THAT is real. A real building has been transported onto the other.”

“Yes,” Chrístõ said because there seemed nothing else to say. Science had no answer. Magic was only science by another name for the superstitious – or as Kohb said, clever tricks.

A miracle, demonstrating the might and power of the gods was the only explanation he could think of right now.

And that troubled him.

Because he wasn’t sure he believed in those sort of miracles.

“Let’s get back to our hotel,” Chrístõ said. “Whatever this is, I need to think about it.”

By the time he had reached the hotel Chrístõ was sure of one thing. This was something he needed advice about. The first thing he did was put a call through to his father. He told him about everything that had happened.

“These manifestations? They looked genuine?” His father asked. “The news is already coming in. People are talking about it across the galaxy. But you were there, to see it first hand?”

“It looked genuine,” Chrístõ confirmed. “But…I’ve never heard of anything like it. Those bodies were desiccated, mummified. There was no life in them. But before our eyes… And then the tower…”

“Rassilon made the Death Zone vanish out of existence,” his father said. “A feat that might well be considered magic or miraculous to those who do not understand our temporal sciences.”

“Rassilon ALLEGEDLY did that something like 30 million years ago, father. No living Time Lord has seen any of his works.”

“Doubting the works of Rassilon is verging on blasphemous on Gallifrey, Chrístõ. Are you really such a cynic? You’ve spent enough time on Earth to know that faith can move mountains.”

“Mountains, perhaps,” Chrístõ answered. “Although again I have not seen any actual empirical evidence. But Temples? It looks as if it had always been there, as if the building work had never been halted. I can see no obvious scientific explanation…”

“Chrístõ,” his father said. “Science was always your passion. But you studied philosophy, too. And you got 94% on your comparative theology elective. Just this once, isn’t it possible that there IS no scientific explanation? The gods of Ubatir have settled the argument once and for all by moving the spire to the place it was always intended to go. I’m not sure it is for us to question that. Put it down to experience. The Conference begins tomorrow, doesn’t it?”

“Yes.”

“There are important issues of interest to the High Council. I trust you will be able to put aside miraculous apparitions and concentrate.”

“I thought you knew me better than that, father,” Chrístõ answered. “I’ll represent our world fully and without distraction.”

“Then that’s all that matters for now.” His father turned to less signifiant matters then and he enjoyed talking to him before closing the connection and turning to where Kohb and Camilla, in a very flattering silk dress, waited for him to join them in a late luncheon after their long morning’s activities.

Camilla reverted to Cam the next morning when they met in the great Conference Hall that was in the base of the Tower, spreading out under the plaza, Chrístõ guessed, unless the Ubatir people had discovered their own version of dimensional relativity.

As they took their places there was a great deal of gossip going around about the events of yesterday. All of the delegates had been present, of course, and had witnessed the manifestation. They were split more or less equally between those who thought it was a genuine miracle, those who suspected a trick, and those, like Chrístõ, who were undecided. The Ambassador for Rabr Acer was unique in being convinced it WAS real, but forced to deny it because it conflicted with his own religious belief that Rabinar was the only true god. He had a three way split in his own mind.

“Whether it is real or not,” the cement-like Ambassador for the planetary state of Fahot said with a rumbling cadence to his voice. “The people here are already being affected. Do you know what happened yesterday afternoon while we were having a diplomatic lunch?”

“No, what?” Kohb asked him.

“All the scientists working in the Tower were put out of their laboratories and escorted to their homes. They are under house arrest, forbidden to practice. Science has been deemed blasphemous.”

“And this morning the High Priest announced that all books and works of art in the city were to be scrutinised and those considered blasphemy would be destroyed,” said the Aletian Consul.

“Book burnings?” Chrístõ mused. “That’s not good. And how can they possibly say that science is…” But the chairman of the conference was taking his seat and they were called to order. All further discussions of matters not relating to the issues on the conference agenda would have to wait.

They made good progress during the morning. The first half a dozen points on the agenda were debated and voted upon. Everyone was glad to take a break and leave the air-conditioned conference chamber for the bright sunshine and fresh air of the plaza above.

Except there wasn’t any fresh air. The air was tainted by the smell of burning paper, canvas, varnish, paint and wood as the works of art and literature deemed blasphemous were thrown onto a bonfire. Chrístõ watched in dismay. He had expected that, but not so soon.

He looked around at the crowds. He wished fervently that his telepathic nerves were not still shredded. He would be able to gauge the real feelings of the people. There was little to be read in their faces as they watched the bonfire being fed by more and more material.

“A religion that fears art and literature,” Kohb noted.

“Censorship of thought and individuality,” Cam added.

“Fascism,” Chrístõ said. “That’s the word for it.”

“What’s going on there, now?” They turned and watched as a group of people were escorted under guard from the Tower.

“Poets and artists,” Kohb said. Chrístõ looked from the detainees as they were brought into the middle of the plaza to Kohb.

“You can read them?” he asked. “Your telepathy… you can do it?”

“Yes,” he answered. “There are very frightened people. Apparently there has been a whole new set of pronouncements this morning.”

“I don’t get it,” Chrístõ said. “They didn’t SEEM to be wrathful gods. They were annoyed about the spire, but they sorted that out. Religion is figuratively above science and art. They don’t need to interfere in those things.”

The High Priest stepped into the middle of the plaza and a silence came upon the people. They waited for him to speak.

“Blasphemy will not be tolerated,” he said. “From hereon it is decreed that the only books that will be printed, the only art that will be made, must be dedicated to the glory of Ubaz and Ipotir. Dissension will be punishable by imprisonment.”

Most of the people accepted that news. One didn’t. A man broke away from there detained writers and artists, and tried to stop the priests from throwing another batch of paintings on the fire.

“No,” he cried. “Those are mine. Give them to me. I will keep them in my own home, private. I will let no one see. But give them to me.”

The priests shrugged him away. He fought back. There was a scuffle. And then, it was nobody’s fault, all the witnesses said so, but the man lost his footing and fell towards the fire. His clothes, the working clothes of a man who worked with paint and linseed oils, caught fire. He screamed in agony, but the priests continued to throw paintings and books onto the fire.

Chrístõ was the only person who moved. He ran towards the man, pulling the burning clothes off him, rolling him on the ground to douse the flames. His own hands burned but he didn’t worry about the pain. He knew he would heal.

The man was badly burnt. Though not so badly that he wouldn’t live. He could be treated.

He could have helped him now, with the tissue repair mode of the sonic screwdriver. But he had an idea that would be deemed blasphemous. The best he could do was call on some of the citizens to bring him to where he could be looked after. He had to call twice before anyone was prepared to defy the High Priest and do it. But eventually the man was carried away.

“Come on,” Cam said when Chrístõ returned to their side. “I’ve seen enough. Let’s get back to the conference room, where sanity and logic still hold some value.”

“I can’t,” Chrístõ told him. “After that. I just can’t.” He clenched his palms together, feeling the burns mend themselves. It wasn’t the physical injuries that bothered him, through. It was the fact that a man almost burnt to death and nobody was prepared to help him because it went against the will of their god.

There were tears in his eyes as he turned from the scene. He wasn’t the only one. Among the crowds watching there were many who had been unable to disguise their feelings about what they saw. But he WAS the only one who had a trade alliance to forge this afternoon.

“Chrístõ!” Cam held him by the shoulders and spoke in a firm voice. “I understand you. But you must go back in there. Be professional. Be diplomatic. And try not to let these scenes distract you.”

“How can I not… I can’t forget what is happening here. It is so very WRONG.”

“We know,” Cam assured him. “But we have to do what we came here to do. Chrístõ, my friend, your father would tell you the same. You know he would.”

“I need to talk to my father,” he answered. “I need…”

“There’s no time,” Kohb told him. “We are due back in the chamber.”

“Come on,” Cam said gently. “Talk to your father later. But I guarantee he will say the same.”

Chrístõ came to the debating chamber. He had no other choice. But his heart wasn’t in the work. He was not alone. And when, at the end of the afternoon session, the Alterian Consul proposed a vote of censure against the authorities of Ubatir for allowing the totalitarian actions they had all witnessed there were plenty of volunteers to second the proposal. The vote of censure was put on the agenda for the next morning’s order of business.

The fires were out by the time they emerged from the chamber. The plaza was empty. The people had been ordered to go to their homes. The tower was silent and empty.

“Two days ago these people were happy,” Chrístõ said to his father on the videophone. “Now…. orders, pronouncements. And father, What do I do? This planet is in my presets. The Time Lords wanted me to do something here. But surely they don’t want me to fight against the established religion of this world? That would be utterly against the very precepts of our society. We have never interfered in such a way. As for the diplomatic implications…”

“The diplomatic implications are clear. You must remain impartial. This vote of censure. It is a hasty action, based on emotion. I am surprised so many professional people are involved in it.”

“You weren’t there, father. You didn’t see. If you did, I would be disappointed if you had not PROPOSED the vote.”

“That’s as may be. But I don’t think it will do any good. And nor do the High Council. You should vote against it.”

“Is that an order?” Chrístõ asked. “Because if it is… it puts me in a difficult position. Because I mean to vote FOR it. And I won’t be ordered to act against my conscience. I was appointed to this position because you and others believed in my ability. You never meant for me to be a mere puppet of the High Council did you?”

“I did not,” his father answered. “Nor did those who approved your appointment. But be guided in this. Think about it overnight at least. Consider the implications for…”

His father’s image shimmered and was cut off, replaced by a ‘connection lost’ message. He tried to reconnect but nothing happened.

“Chrístõ,” Kohb said, entering his private room without knocking, which surprised Chrístõ enough to make him turn from the viewscreen and look at his friend and aide carefully.

“What’s happened? And is it anything to do with the fact that I can’t get a videophone connection?”

“It’s everything to do with it,” Kohb answered. “Intergalactic communication has been deemed blasphemous. The uplink to the satellite beacon has been cut.” Kohb nodded meaningfully and Chrístõ turned to see a new image on the screen. It was the High Priest telling the people of Ubatir that television would henceforth be used for the dissemination of the good word of Ubaz and Ipotir and for no other blasphemous purpose. Chrístõ turned the screen off in disgust.

“I can contact my father using the TARDIS commutations,” he said. “It doesn’t rely on uplinks.”

“Not now, you can’t,” Kohb answered. “There is a curfew in force and your TARDIS is at the spaceport.”

Chrístõ swore loudly in a mixture of Low Gallifreyan and demotic English that would have made both his father and mother very alarmed to find that he knew such words.

“Feel better?” Camilla asked when he ran out of curses. Chrístõ looked at her and couldn’t help smiling. She looked as stunning as she did the first time he met her in a deep red satin dress shot through with gold which was the key colour of her hair and make up.

“The Ambassador of Lmevoi Jquiwr invited us to take supper in her suite,” Camilla reminded him.

“That’s the six foot lady with the knee length auburn hair and bronze wings,” Kohb reminded him. “You danced with her at the cocktail party and for some reason mentioned that you are good at backgammon. As she is the grand master champion of her planet, she naturally wishes to challenge you after supper.”

Chrístõ was reluctant. He would much sooner go and get his TARDIS, contact his father and…

And what, he wondered? Resign? Leave the planet? Give up?

He never shirked difficulty before. He wasn’t going to start now.

“There’s nothing I can do until tomorrow,” he told himself. “When the curfew is lifted I can either go to the chamber and vote for or against the censure, or I can go to my TARDIS and start finding out what this is REALLY about.”

And an evening of backgammon with a lady with wings attached to her shoulder blades was not the worst way to pass the time. Maybe he did need to take his mind off things for a while.

“Have you ever visited Lmevoi Jquiwr?” he asked Camilla.

“Yes,” she answered. “It is a charming place. Very peaceful. Very clean air. A lot of birds. Not surprising since the indigenous species evolved from them.”

“Sounds wonderful. I must take Julia in the spring. But just promise me…. Backgammon isn’t one of their mating rights? I remember how she looked at me when we danced. I don’t want to end up engaged to her before the end of the evening.”

“Chrístõ, you really must get over your fear of strong willed and attractive women,” Camilla told him with a smile that could only be described as wicked.

Chrístõ managed to avoid being betrothed against his will. He did win one of the games of backgammon. And between the four of them, with their various experiences the ambassadors and ambassador’s aide puzzled some more about what was happening to the planet they were guests of. All agreed that the new developments were bad. The Ambassador for Lmevoi Jquiwr had visited before and found the people charming and well-educated and hospitable, which was how Chrístõ and his companions would have described them up until two days ago. Now, they were becoming cowed, beaten people who lived in fear of the wrath of their gods.

But none of them could answer one over-riding question.

WHY were the gods who had given blessings on the people before, now making their lives so difficult? Why the oppression of free thought among their followers? Why the cruelty they had witnessed so far? It made no sense at all.

The next morning the delegates were all experiencing various levels of depression and uncertainty as they made their way to the conference centre. They all looked up at the Spire on top of the Tower with trepidation. What had once been two beautiful monuments complimenting each other not only in architectural style, but in their purposes, now seemed to represent only fear. And that fear radiated out from it, affecting all who walked in its double shadow.

But they had a job to do. And they got ready to do it. They sat at their tables once again, ready to begin the day’s work with that vote of censure.

“Have you decided how to vote?” Cam asked Chrístõ as he reached for a glass of water and sipped it slowly.

“Yes,” he answered. “You?”

“I never managed to contact my people before the communications were cut. So they haven’t put any restraints on me. I’m voting for the censure, without reservation.”

Chrístõ didn’t say anything more. Cam looked at him and wondered if he ought to ask. He understood his dilemma. He wanted to vote according to his conscience. But he had been instructed to do otherwise. If he disobeyed the consequences for his future in the diplomatic corps were dire.

If he obeyed, he would go against his own nature.

“My people would probably have told me the same,” Cam told him. “If it makes you feel any better.”

“It doesn’t,” he answered. “But thanks, anyway.” They both sat up straight as the chairman called for attention. He read the first item on the agenda. Chrístõ felt his stomach churn as he prepared to take a decision that, either way, could change his future.

But the vote was never taken. As the chairman was reading the carefully worded censure, the door to the chamber crashed open. A phalanx of priests, followed by soldiers with weapons ready, marched down to the centre of the chamber. The High Priest looked around at the puzzled delegates and pointed to certain of them. The soldiers and priests moved forward and took the ones picked out. The bronze winged Ambassador for Lmevoi Jquiwr was one of them. The Ambassador for the planetary state of Fahot was another. The Consul for Idi Sextus, bald, with pale blue skin and one central eye was taken. The reptilian-skinned Matrix of Ay'Ydiwo was taken.

Chrístõ realised what was happening a few moments before all the others.

“All the non-Human looking delegates,” he whispered. “The gods must have made some kind of decree to say anything non-Human is blasphemous.”

“But we’re diplomats,” Cam protested. “We have immunity.”

“Not any more,” Chrístõ noted. “Apparently.”

Then his hearts froze as the High Priest pointed at them. Two soldiers came towards their table. Kohb reached out for Cam’s hand. Cam reached out his other hand and grasped Chrístõ’s.

Cam was pulled roughly from his seat. Kohb gave a cry of anguish. Chrístõ, too raised his voice in protest. They were both forced back as they tried to stop Cam being taken to join those singled out.

“Why him?” Kohb demanded. But he knew why. They both did. ALL the delegates did. They had all seen Camilla at the parties and receptions in the evening, Cam at the delegates table the next day. Changing gender was as blasphemous as having blue skin or a reptilian tail, or bronze wings.

“Why not us, then?” Kohb asked quietly. “We’re different, too.”

“Only on the inside,” Chrístõ noted. “They banned science. That included medical science. They have no way of seeing our two hearts and our respiratory bypass system or our orange blood.”

“Where are they taking her?” Kohb asked as the group were pushed and shoved and harried towards the door. The soldiers kept their guns trained on the rest, making any effort to intervene impossible.

“We should have tried,” Chrístõ murmured. “While they were in a confined space. We could have tried. We could have rushed them.”

But he knew they couldn’t. He and Cam and Madame Denvoi of Lmevoi Jquiwr were the only ones who could be described as ‘young’. Diplomacy was a job that usually attracted mature people. And his own father was probably unique in having come to it from a military background. These were people whose weapons were words. They were unfit and unprepared to take on armed soldiers.

“You will remain here,” they were told. “Until the preparations are done.”

“What preparations?” The question was echoed around the room as the hostages and the soldiers left the chamber. The door was slammed shut and nobody needed to check. They knew it was locked and guarded. They could do nothing but wait.

They waited two hours before they were finally told they could go to their hotel. They would, of course, be under house arrest there. But they would be otherwise accorded every courtesy.

“Courtesy?” Kohb spat the word bitterly as he walked with the rest out into the sun-drenched plaza.

When they reached the plaza, they felt nothing but horror.

In the place where the Spire had stood until a few days ago stakes had been erected. And tied to them, two or three to a stake, were the diplomat hostages, along with dozens more people from the indigenous population. The scientists who had been put under house arrest on the first day, and others who had dissented. Chrístõ was disgusted to see the man who was injured yesterday, his burns still bandaged, tied up there with the others.

They must already have been standing there for at least an hour, with the two hot suns beating down on them. Some of them were already suffering. The Fahotian Ambassador looked as if his concrete-skin was cracking. Many of them were fainting, their bonds holding them up as their heads lolled forward.

“Camilla,” Kohb whispered hoarsely as he saw his lover among the crowd. Technically it was Cam who was held. He was still in the male form. He was tied up with two of the indigenous people. They were all suffering.

“We can’t do anything here,” Chrístõ said. “We’ve got to get away from here. I need to get to my TARDIS.”

“You could materialise around her.” He said. “Maybe some of the others, too. But there are so many. Can we…”

“TARDIS first. On three, time fold.”

Chrístõ touched Kohb’s hand and tapped three on his palm. They both steeled their hearts and folded time in unison. Their figures blurred as they broke from the crocodile of delegates and ran. Chrístõ wished fervently that the remote control still worked on his TARDIS or that he had taken a leaf from his father’s book and always kept his TARDIS in his suite when he stayed in a hotel.

As it was, they had a long trek to the space port, and they expected a lot of security when they got there.

“This is not going to be a diplomatic solution,” Chrístõ said as they came out of the time fold and walked down a back street of the city, trying to look as if they belonged there.

“Diplomacy no longer counted the moment the debating chamber was invaded by armed soldiers,” Kohb answered. “But please… Help her.”

“She’s always Camilla to you, isn’t she,” Chrístõ said. “Even as Cam. You just don’t see the man. I never realised it before. You only ever see the woman you love.”

“Yes,” he replied. “And I can’t let anything happen to her.”

“We’re not going to. Come on.” He touched his hand again and they folded time once more. The streets were quiet. Even though there was no curfew, people were reluctant to come out unless they had to. Most of those who had ventured out had gone to the plaza. But he knew the closer they got to the spaceport the trickier it would be.

And he was right. The entrance to the port was ringed with soldiers. They were checking every vehicle that went near. Kohb and Chrístõ peered around the side of an armoured personnel carrier that was parked by the outer perimeter.

“I suggest a little automobile theft,” Kohb said, looking at the APC. Chrístõ reached for his sonic screwdriver.

“Blasphemous sonic screwdriver,” he said wryly as he applied it to the door and heard a satisfying click. Chrístõ climbed up into the driver’s seat. Kohb sat beside him. He reached to put the vehicle into gear. His first plan had been to bluff his way through the checkpoint using Power of Suggestion and psychic paper. But as he felt the power steering beneath his hands he had another idea.

“To hell with diplomacy,” he said and he pressed his foot down on the accelerator. The soldiers dived out of the way as the APC crashed through the gate. He turned the steering wheel as bullets hit the armour plating. He headed for where he had left his TARDIS, disguised as a small personal shuttle. He swung the APC around beside the bay where he had parked it. Kohb was ready straight away to jump out. Chrístõ followed him. Bullets were still hitting the APC and there were shouts and sounds of running feet, but they were shielded by the bulk of it as he pulled out his key and opened the TARDIS door.

Kohb slammed the door shut behind them as Chrístõ ran for the console. He dematerialised the TARDIS as a hail of bullets hit the outside.

“Kohb,” Chrístõ said quietly as he studied the lifesigns monitor. “I’ve located the hostages. I can differentiate between the species, more or less.”

“You know which is Camilla?”

“Yes,” he answered. “But… these two… That’s the Ambasador for Fahot – cement man – and that’s one of the lizard species. And these two are ordinary citizens of Ubatir. And they’re all severely dehydrated and weak already. Cam… he… she’s all right at the moment. She’s coping.”

He looked at Kohb. His telepathy was still faulty but he didn’t need it to see the dilemma on his face.

“Save them first,” he said. “Camilla will understand. I hope.”

Chrístõ nodded. He set the materialisation for as wide a field as possible. But he knew he couldn’t reach Cam and save those who needed his help most right now.

“I’ll get her on the second run, I promise,” he said as he pressed the materialisation switch.

He managed to grab at least thirty of the hostages, stakes and all. They both ran to cut their bonds. The Ambassador for Fahot looked as if he was melting. The reptilian man collapsed onto the TARDIS floor as soon as Kohb cut through the ropes that bound him.

Help them both to the bathroom,” Chrístõ said. “They’re both over-heated and dehydrated. Put them in the shower.” He turned to the console again and began to calculate a rematerialisation that would bring more people into the TARDIS. As he did so he saw the incoming communications light flashing urgently. He reached and turned on the viewscreen.

“Chrístõ!” his father looked relieved to see him. “You’re in your TARDIS?”

“Yes,” he answered.

“Get away from that planet, now. There are three warships in orbit about to declare war for the kidnapping of their delegates.”

“I just know OUR government didn’t send one,” Chrístõ noted dryly.

“The President of the High Council sent an official protest. But the Fahot government are prepared to open fire on the capital if there is no response within the next ten minutes.”

“I HAVE the Fahot Ambassador,” he answered. “He’s in the shower with the Matrix of Ay'Ydiwo.”

“Come again?” his father half smiled despite the seriousness of the situation. Chrístõ realised there was probably a better way to phrase that statement. “Never mind. I’ll contact the Fahot government and tell them their man is safe. And Ay’Ydiwo”

“I’m going to get the rest,” he said. “I’m not going to leave anyone in danger.”

“I would have expected nothing more of you. But, Chrístõ, you asked what you were supposed to do there. I think the only thing you CAN do is get the delegates out and leave. There is nothing you can do about the situation there.”

“That’s what I was sent here for? To run?”

“This time, yes. There’s nothing else. Do what you can. But do it quickly. Good luck, my son.”

The communication broke off. Chrístõ turned to the materialisation switch again. Another thirty or so people were liberated. Cam was one of them. He kept his promise to Kohb.

“That was amazing,” Cam told him. “The TARDIS appeared as a smaller version of the Great Spire. When it dematerialised and took people with them the High Priest said it was the gods taking them to judgement.”

“Is he making all this up as he goes along?” Chrístõ asked as he prepared to do a third materialisation. As his hand reached for the switch, he thought about what he had just said and he began to understand something about this whole situation.

Hostages first, he decided. Then explanations.

It took two more carefully co-ordinated broad materialisations to reach the rest of the tethered people. All of them were relieved. All revived physically and mentally with basic first aid and the knowledge that they were safe.

“But what about the others,” Madame Denvoi asked. “Our staff, the other delegates under house arrest at the hotel. And what about those who BELONG on the planet below?”

“I’m going to sort it out,” Chrístõ answered. “Everyone is going to be ok. But first I’m going to have a word with Ubaz and Ipotir.”

“But your father said…” Kohb began.

“My father isn’t always right,” Chrístõ answered as he set his next co-ordinate for the Spire Temple. “I’m about to commit a blasphemous act. Who wants to join me?”

The High Priest was in the Temple. So were several of the lesser priests. They were giving Ubaz and Ipotir an update of the efforts made to ensure devotion to them among the people of Ubatir. The gods sat on two gilded chairs either side of the altar and drank red wine and ate fruit as they listened.

Their robes billowed and the High Priest’s headdress blew off from the air displacement as the TARDIS materialised as a statue on a plinth. Chrístõ stepped out first. He looked up and saw that the statue was Lord Rassilon, the closest thing to a god of Time Lords. He smiled as he turned to address the gods of Ubatir. He didn’t bow or prostrate himself, or any other sign of obeisance. The TARDIS had rather neatly reminded him of one thing.

He didn’t believe in gods. Even ones that DID exist.

“Because that’s the thing it took me a while to figure out,” Chrístõ said out loud, ignoring the protests of the High Priest and his underlings as they were restrained by the sturdier of the delegates who had succumbed less to their exposure to the heat of the midday sun. “You ARE real, aren’t you? It’s not a trick. You really ARE the gods of Ubatir come back to corporeal life before our eyes. I was too busy looking for the teleport or the hologram projector. I never considered that it was real.”

“Of course we are real,” Ubaz answered him indignantly. “You are not of Ubatir?”

“No, I am not. THESE people are.” He turned and saw the group of scientists and dissidents bowing to the gods. They looked scared. “I want to know, on their behalf, why you have subjected them to suffering and torture.”

“WE?” Ipotir replied in clear surprise and indignation.

“But we love the people,” Ubaz protested. “We mean them no harm.”

“No HARM?” Chrístõ replied. “They are being imprisoned for THINKING. They are dying.”

“No!” Ipotir declared. “No, that can’t be.”

“Have you looked outside of your temple? Have you seen the devastation out there? The ruined lives? What sort of gods ARE you? Certainly not omniscient ones!”

“When we take on corporeal form we are no longer omniscient,” Ubaz told him. “For the length of the time of the manifestation we are as mortal men. We have given our decrees to the High Priest and he has carried out our orders.”

Chrístõ looked at the High Priest. He was being held by two blue skinned victims of his pogrom. He had the appearance of one who knew the game was up.

“WHAT decrees have you given to him?” Chrístõ asked.

“We decreed that there should be a week of festivities and feasting and all of our people should rejoice,” the two gods answered together, sounding much more impressive in stereo than they did singularly. “The High Priest has told us that it has been done.”

“You didn’t order the closing down of the science laboratories and the burning of blasphemous works of art and literature? You didn’t order all non-humanoids to be rounded up and exposed to die slowly in the plaza?”

“WHAT?” the stereo sound turned up a decibel. “Bring the High Priest forward.”

The High Priest was dragged forward, on his knees. Ubaz rose from his gilded seat and touched him just once on the shoulder.

“Ah!” He cried out and his brother god looked as distressed. “What evil is this? Hidden behind a pretence of piety. You USED our manifestation to take power for yourself. You wished to rule. You have done all of this. And in OUR name!”

“Lords,” he answered. “There was so much blasphemy.”

“No,” Ubaz said to him. “We only wished to see the tower completed with our temple placed above the secular arts and sciences. We wished it to be known that our protection and patronage is upon those accomplishments of our people. But you…”

“Chrístõ!” Madame Denvoi ran from the TARDIS, her bronze wings opened spectacularly. “Your father has sent a message. He is unable to get through to the Fahot government. Their warship is about to fire on the city. They are aiming at this tower.”

“Everyone in the TARDIS, now,” Chrístõ answered. “You’ll be safe in there. The TARDIS can withstand explosions. Take those idiots.” He turned back to the two gods. “You said you are as mortal men for the time of manifestation. I suggest YOU also seek the protection of my ship or your mortality will be tested.”

“There is no need,” they answered. “YOUR faith will be tested.

The temple shuddered as the energy beam from the Fahot warship enveloped it. For a few seconds Chrístõ saw the walls around him and the floor beneath his feet disintegrate in a ball of fire. Moments later the temple was intact but glowing with a silvery light. The two corporeal gods hadn’t moved a muscle.

“You doubted our power?”

“Yes,” Chrístõ answered them. “And clearly I was wrong about that. But you were wrong to trust your High Priest. You have a serious PR issue and a showy bit of self-preservation isn’t going to be enough. I suggest that you come with me now. Along with him.”

The High Priest was shaking with fear. Not because he survived the obliteration of the Temple he was in, but because it proved the true power of the gods he had tried to cheat. Chrístõ realised he had not been the only one who had not entirely believed in Ubaz and Ipotir. That was why the high priest had thought he could take advantage of their manifestation.

He had intended to bring the two gods into his TARDIS. They had other ideas. The movement was subtle, but everyone knew what had happened. It was the second time it HAD happened, after all. Chrístõ followed Ubaz and Ipotir as they walked towards the door, indicating with a wave of their hands that the captive High Priest and his underlings should follow. The rest of the people came out of the TARDIS and followed behind them as they all stepped out of the temple into the plaza. The Spire had been returned to the spot where it had stood since it was first built. In the plaza, the citizens of Ubatir fell to their knees as their gods walked through the crowd. They had seen two miracles already today. First the tower surviving a direct hit from the Fahot energy weapon and now the second transportation of the Spire.

And now their gods walked among them.

Their gods began to speak. They asked first for the man injured in the burning of the art to be brought to them. Before everyone they saw his wounds repaired. Then they called forth the High Priest to determine how he should be punished.

Chrístõ didn’t bother to watch. He turned back into the temple and went to his TARDIS. He quickly made contact with the three warships above the planet and assured them that the crisis was over.

“Ubaz and Ipotir are putting everything to rights,” Kohb said, as he and Cam stepped into the TARDIS. “Apparently they can even restore the art and literature that was destroyed.”

“They’re gods. They can do what they like,” Chrístõ said.

“What about us? Do you think the conference will continue?”

“It’s what we came here to do,” he answered. He turned to the computer database and looked at the list of presets. He could count this as one of his successes after all. He felt better about it than if he had had to run with as many refugees as the TARDIS could carry.

“I don’t suppose it matters now,” Cam said to him. “But the censure. How were you going to vote?”

“It DOESN’T matter, now,” he answered. Cam smiled and nodded.

“You WOULD have made the right decision, either way,” he told him. “Be sure of that.”

|

|

|