Jenny Flint peeled an orange and ate the segments slowly. They eased her thirst on the long train journey.

Funnily, the journey through France to Menton, where the oranges came from - these had been sent to them especially, wrapped in waxed paper and sealed in a big wooden crate - didn’t seem as tedious. Of course, part of that trip involved sleeping overnight in a comfortable berth and there was dinner and breakfast to break up the time. For this journey to the north-west of England there was much less variety. The carriage was self-contained with nowhere to stretch their legs at all, and certainly no dining car. After hurried calls of nature at Coventry station, Madame had purchased a lunch basket from a vendor on the platform. They ate the cold collation in the carriage as the train rumbled on towards the industrial sprawl of Birmingham. The food was nice, but the bottle of raspberry cordial supplied for a drink didn’t seem to go far enough.

The oranges filled the carriage with a smell that both Jenny and Madame liked, the waxy, bitter skin, the sharp citrus of the flesh reminded one of those sultry days in the south of France and the other of a time long past, before at least one continental break up, when London was a tropical paradise.

There was no-one else in the carriage to complain. An elderly banker had been with them from Euston, but he seemed to find their company worrying, especially after Madame had let slip in the polite conversation that they were in fact a married couple. The bemused man had sought a different carriage at the first opportunity, a situation that suited them both perfectly well.

“Still another two hours,” Jenny sighed. “Train travel is dull.”

“We used to have a system of pneumatic pods underground,” Madame Vastra said with her usual sad tone of reminiscence. “We could travel hundreds of miles in a few minutes.”

“That would do me right now,” Jenny agreed.

It was a rather odd errand they had embarked upon. It had started with a letter received by Madame at breakfast two days ago.

“Bad news?” Jenny asked as she saw Madame frown at the message, an expression that was thoroughly enhanced by her thin, reptilian lips.

“Yes, but not for us, personally. Somebody I have known for some time has died. The funeral was yesterday, but there are personal effects to be disposed of, and it appears that she asked for me to see to it.”

The lady was called Mary Wheaton, and Madame had first known her some twenty years ago when she was a seamstress – Mary Wheaton that is, not Madame, perish the thought. Mary was in her sixties then, and her eyes were not what they used to be for dressmaking. Madame had actually arranged for a small pension and a place for Mary to live in much-deserved retirement.

“That was kind of you,” Jenny said as they travelled north to Camden, Strax driving the carriage as usual.

“Don’t sound so surprised, my dear,” Madame answered. “I CAN be kind. Truth be told, Mary was kind to me. When most people were startled by my appearance, and some disposed to be unpleasant… though only the first time they encountered me… Mary said things like ‘nobody can help how they’re born’ – although she said it with a broad Lancashire accent I could not begin to imitate.”

There was a smile on those thin lips. Jenny thought Madame must have been fond of this elderly woman. Perhaps when she was twenty years younger, she had appreciated a non-judgemental ‘mother’ figure in her life.

Did her kind have mothers? Did they have family units in that sense? That was one of many things Jenny didn’t know about Madame’s distant past.

Mary Wheaton was a revelation from her more recent history.

The place where Mary Wheaton had gone to live a quiet, simple retirement was one of St. Martin’s in the Fields’ almshouses on Bayham Street, Camden. They were rather nice little places, Jenny thought, like country cottages slapped down in the middle of the city. They had a little parlour and kitchen, with indoor plumbing, and a bedroom, all very cosy and pleasant. Anyone from Jenny’s east end streets would have thought they had died and gone to heaven if offered such accommodation.

Being allocated an almshouse was a difficult process, though. Not just anyone was accepted. An applicant had to prove themselves of good Christian character and usually a sponsor of some kind was required. Madame had obviously called in some favours for her old friend. Again, Jenny was surprised and gratified by this example of largesse from one who was so often cold and disparaging of humans as a species - yet could be so generous to individual humans.

A Miss Hannay received them in the parlour of her warden’s apartment which was very much the same as the other houses but with more personal effects adorning the sideboard. She offered them tea and expressed her sorrow that Mary Wheaton had passed away.

“Of course, she was in her eighties, a good age. It comes to us all in our turn, and it was peaceful in the end.”

It seemed as if Mary had expected it to be coming to her. She had packed up everything that mattered to her.

Jenny thought it was precious little for a lifetime. It all fitted into a small suitcase, probably the same one she brought when she moved into the almshouse. There had been a letter for Miss Hannay to ask her to contact Madame Vastra at Paternoster Row and one for Madame herself. She opened the thin, cheap envelope and read the note while Miss Hannay was making the tea. She raised her eyebrows once and passed the sheet to Jenny, who was agog with curiosity.

Mary Wheaton had asked the only friend she could trust to find her daughter, born sixty-two years ago, and give her the contents of the suitcase as her small legacy to her child. To facilitate this quest, she enclosed a very old and grubby piece of paper that proved to be a birth certificate. The baby was named Sarah Wheaton.

“She wasn’t married to the father,” Jenny noted. There was nothing very unusual about that, of course. London was full of unmarried mothers. Men were notorious for leaving unfinished business behind them. Especially the sailors who frequented the port -hinterlands.

“The child was born in the outside relief hospital of the old Whitechapel workhouse,” Madame noted. “Outside being important. Neither she nor the baby lived there for any length of time.”

“Then where do we begin to look for Sarah Wheaton?” Jenny asked. Madame didn’t answer straight away. Miss Hannay was back with the tea. It was probably too late to worry about it now, but having an illegitimate baby was the sort of thing that would have counted against an applicant to the almshouse charity. It was hardly considered ‘good conduct’ and Christian men and women could be very judgemental about these things. Madame decided to keep her late friend’s reputation intact and withheld that information from the warden.

“I know where she took the baby,” Madame said when they were back in the carriage. She held up a small silver object – half of a rather prettily made locket that might once have been considered valuable.

“Of course, the Foundling Hospital,” Jenny guessed. The locket was one of the famous, or infamous, tokens by which a mother could reclaim her child from the institution if her circumstances improved. There was a sad little museum display of such things in the foyer of the building suggesting that reclamation was often a forlorn hope.

The tokens were not strictly necessary as the hospital had long since begun to give written receipts, but the custom prevailed, perhaps because such tokens lasted better than paper receipts.

“She would have had to convince the board that she and the child were abandoned by the father and that she was of previously good character,” Madame said. Jenny nodded. Long before convincing the Board of St. Martins in the Field that she was worthy of a place to spend her last years in comfort her ‘conduct’ had been under scrutiny by another committee of stern and critical people who held her future in their hands.

“She must have been of good character, then,” Jenny had suggested. She knew well the fate of women who couldn’t prove themselves. It was a harsh and unforgiving world for them.

“She never talked openly about her past,” Madame admitted. “Even the baby is a surprise to me. But she did say once that she had gone down in the world since her childhood. She spoke well, despite the dialect, and you can see she could write well enough, so she had an education before free schooling was made available to the poorer classes of England. Yet she was never bitter about the hard knocks of her life. I think that was one reason I found her so likeable. I do wish I DID know more about her, now. Did she have ANY family? Was there anyone to mourn her at her graveside? I should look into getting a headstone made. The St Martins charity would have ensured a proper burial, but I doubt they would run to a memorial stone.”

Again, Jenny noted that streak of generosity in her lover. Some of it came from The Doctor who had been the first to show her any kindness. Jenny, too, took credit for making her a little less abrasive in her dealings with the ‘stupid apes’ of her acquaintance. But there must be something deeper within her lizard species soul that made her this secret benefactor to the needy.

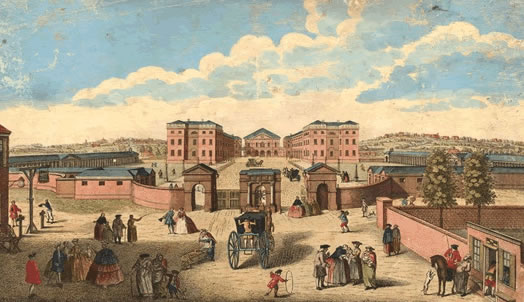

The Foundling Hospital was also in the borough of Camden, a many storied, sprawling Georgian institution at a place called Lamb's Conduit Field. The part of it that members of the public were permitted to see was an echoing series of halls with marble floors and high ceilings, the walls adorned with famous pieces of art donated to one of the favourite charities of the upper classes.

They never saw sight or sound of a foundling of any age, though thousands of them lived here, daily washed and fed and taught skills that would prevent them being a burden on society in the future.

But the hospital, opened in 1741, was remarkably efficient when it came to record keeping. After only a short wait a Miss Atkins showed them a ledger recording the fact that Sarah Wheaton had, indeed, been placed in their care when she was three months old, her mother having been promised a good ‘living in’ job provided she had no dependents. Another such ledger showed that Sarah had been clothed and fed and educated to the level expected of a girl of humble station and, at the age of sixteen, finally left the hospital to take up a suitable apprenticeship.

“You have a record of where that apprenticeship was?” Madame asked.

I do, and I am writing it down now, but there IS a further note here about Sarah,” said Miss Atkins in some surprise. “It says, 'ask Miss Forster'.”

“Who is Miss Forster?” Madame asked.

“She was a foundling herself, once. She stayed on learning to look after babies and eventually became matron of the nursery. She is an old lady now. The directors let her continue to live in a small flat in the staff wing. I can take you to see her, right now.”

Madame and Jenny were brought to a part of the huge building with lower ceilings and narrower stairs, without so much marble and polished wood but still adorned with lesser pieces of art. Here were the private rooms of the nurses, teachers and administrators who kept the institution running smoothly.

Miss Forster was at least as old as Mary Wheaton had been, and arthritis made it hard for her to stand up to greet her guests. Madame spoke gently to her as she settled back down.

Yes, she remembered Sarah Wheaton.

“She never had a day’s illness in all the time she was here,” Miss Forster said. “Not one runny nose or winter cough.”

When contagious illnesses went through the dormitories, as they did despite the scrupulous cleanliness of the institution, Sarah was never sick.

“In fact, she was a little miracle,” Miss Forster said. “Not only was she never ill, but put a poorly child to bed with her, and the child got well, even when it was diphtheria.”

“Really?” Jenny raised her eyebrows. That was a killer disease, one that usually necessitated strict quarantine of the infected, not putting them to bed with a healthy girl.

‘As God is my witness,” Miss Forster said. “Of course, I never told anyone. The directors are church going Anglican men. They believe in the Lord, at least during their prayers. But they wouldn’t believe in a girl with the healing touch. I never said a thing. But it’s the truth. That girl was special.”

“Remarkable,” Madame said, and didn’t give any indication that she believed or disbelieved the story.

“I thought she might have stayed on to look after the youngsters the same as I did,” Miss Forster added. “But the director insisted she should be apprenticed. To a milliner of all things. A miracle girl like that making fancy hats for ladies. What a waste.”

A milliner in Saint Pancras, in fact. Miss Atkins had the full address.

An apprenticeship was a serious undertaking, of course. It required the employer to take over the feeding, clothing and moral guidance of the apprentice for a period of seven years.

It was something else that required records to be kept, so even though Sarah would have finished her apprenticeship at the age of twenty-two, in the year 1855, it might still be possible to find out where she went to after that.

But that was quite enough to be going on with for one day. They returned to Paternoster Row for afternoon tea and a very pleasant supper with Millie’s policeman boyfriend as a welcome guest. He had no new cases that would be of professional interest to Madame, but the spate of high-end jewellery thefts he had recently cleared up made for interesting post-dinner conversation.

The next morning, they set out for St Pancras, where a very stylish shop was still called Madam Lily’s Emporium and listed an L. Vaughan as the proprietor on the sign over the door.

It was clearly a prosperous business. There were three apprentices, perhaps girls who had followed Sarah Wheaton from the Foundling Hospital, as well as two senior milliners and the proprietor herself.

The only problem was that this Madame Lily only looked about fifty or so. To have been Sarah Wheaton’s employer she would have to have been much older than that.

“Oh, you’re thinking of my mother,” said the lady when Madame asked. “She passed the business on to me fifteen years ago. Would you like to talk to her especially or could I help?”

Madame explained her purpose. The younger Madam Lily smiled with delight.

“Sarah Wheaton…. Why yes, of course. Why don’t you come upstairs to the flat? Mother will be glad to meet you, too.”

The flat was pleasantly furnished in an aspiring genteel manner. The elder Madame Lily sat in a comfortable armchair by the fireplace, her eyes showing signs of weakness that must have hastened her retirement from millinery, but she was far from in her dotage. While her daughter hurried to prepare refreshments for visitors several social notches above them the old lady talked readily.

“Yes, indeed I remember Sarah. She was one of my first apprentices. A hard worker, and talented, too. Even before she had finished her apprenticeship customers were asking for her hats. Many apprentices move on when their time is up. It is perfectly usual. The girls are always going off and getting married. But I offered Sarah a generous salary to stay on. She was worth it. A cheerful girl, too. Always happy to talk to customers. She was good to young Lily, too.”

“Oh, she was,” the younger Madam Lily agreed as she brought in a tray. “I must admit the craft did NOT come easy to me. I so wanted to follow mother in the business, but nobody would have bought my first hats, not even to dress a scarecrow. Sarah took me under her wing almost as if I were HER apprentice and helped me get it right. Even now, I don’t have her natural talent for creating original hats. I have to work at it.”

“But she left the job?” Madame asked. “When was this, and… under what circumstances, if it isn’t a difficult question.”

“It was twenty years ago, now,” the younger Lily explained. “The circumstances…. Well, in one way they were quite ordinary, nothing odd at all. In another….”

“It was after that trip to the park,” the elder Madam said. “When she said she’d had a message from her father.”

For a moment, the elder lady had a distant look on her face and Jenny wondered if her mind was wandering a bit too much.

But apparently not.

“We all went on a picnic… one of those organised by a Society, to give workers a day out. Everyone from the Emporium was in their Sunday best, wearing hats made by Sarah and Lily in their spare time. We made a handsome troupe, walking in Battersea Park in the sunshine. It’s a lovely spot, down by the Thames.”

“It was lovely,” the younger Lily said. “Until a little boy fell in the river. There were screams and tears from the mother and nobody seemed to know what to do except Sarah. She threw off her hat and shoes and jumped in after the child. She got him, too. He spat out a lot of water, but he was fine. Then we had a horrible shock. We thought Sarah had been dragged under. We looked all along the river, thinking the worst. Then suddenly she popped up, right as ninepence. She climbed out of the river, dripping wet, looking like one of those… what do they call them in the paintings at the gallery… neryads or something.”

“Naiads,” Madame confirmed. “But she was all right? No after effects? The Thames is hardly the cleanest water in England.”

“She wasn’t sick or anything,” younger Lily asserted. “But she did seem different… distracted, after that. She told me the next day that she’d been given a message… from her father.”

“A message?” Jenny and Madame were both surprised.

“That WAS odd, the older Lily admitted. “First, because we assumed, as a foundling, that she had no father… well, not one that would admit to it. And besides, she’d had no letter or telegram of any sort.”

“I kept thinking that the message came from the river,” younger Lily said. “I know that sounds silly, but there was never any mention of anything like it until after that day. And she went to mother to say she would have to give in her notice. She was going up north to find her father.”

“How curious,” Madame commented, and there was no sarcasm at all. It really did sound like a very sudden change had come over Sarah, one that might or might not have been related to her misadventure in the river.

“So, was that the last you heard of her?” Jenny asked, thinking that they had definitely come to a dead end in their quest, now.

“Not at all,” the younger Lily said. “We had letters…. Cards at Christmas.” She jumped up from her seat and went to the sideboard. After a rummage in a drawer, she came back with a delicately coloured card bearing a ‘seasons greetings’ in curly script.

On the back was a short, friendly message to the two Lilies signed by Sarah Belisama.

“She got married?” Jenny asked.

“No, she chose to use her father’s name,” the older Lily explained. “Strange name, but there you go.”

And there was an address.

The address was in the Lancashire town of Preston, which very conveniently was an important stop on the north-western line to Scotland. Madame purchased tickets for the very next day. Strax wasn’t needed except to bring their bags and the suitcase containing Mary Wheaton’s possessions to Euston Station. He waited on the platform and gave them a rather clumsy wave as they set off.

And here they were, still rumbling towards the north-west of England. Jenny was still enthusiastic to finally meet the mysterious Sarah Wheaton, but this train journey was dull.

And the weather was turning ugly. The sky towards the north was dark as a bruise and the train was rushing towards that darkness and the torrential rain and wind it presaged. Without even a view to look at Jenny was close to moping by the time they reached Lancashire. She positively scowled at the coal-based industry around Wigan, and she was not disposed to be more friendly towards their final destination of the cotton town of Preston. These North parts, it seemed, were as grey and miserable as she had always been led to believe,

“Don’t worry,” Madame assured her as they alighted onto a busy platform of a station that served trains going to all parts of the country including Scotland, the trans-Pennine route and even the famous seaside town of Blackpool. “We’re going straight to the hotel.”

Much to Jenny’s relief, since the rainstorm was still going on, the hotel in question was actually joined to the station by a covered walkway. It was a somewhat steep one in places, and the liveried boy pushing their luggage on a trolley puffed a bit, but everyone was quite dry when they reached the red brick splendour of the Park Hotel. They were swiftly conveyed to a pleasant room where they could refresh before a good supper and an early night.

The night’s sleep restored Jenny’s spirits, and she was revived even more when she looked out of the window to see sunshine beaming down from a blue sky onto a rolling parkland with a river running through it. A train line crossed the park on a high viaduct, and she realised they must have come that way yesterday evening, but in the rain and the bruised sky she had missed the view.

A good breakfast fortified them and then they set off on foot for their visit to Sarah Wheaton’s home. Having eschewed the help of a ‘boy’ from the hotel they took it in turns to carry Mary’s suitcase, which, though a little heavy, still seemed to Jenny terribly little for a lifetime.

Their route took them out through the back of the Park Hotel into that sun warmed green space viewed from the room. They walked along a wide promenade where a formal garden with a fountain dropped away into a shallow basin that could well have served as a flood plain for the river before it was landscaped. They passed under the viaduct and down a slope that brought them to an avenue of tall trees beside the river itself.

“This is the Ribble,” Madame said of the fast-flowing water. “The name comes from a mixture of Celtic and Anglo-Saxon meaning something like ‘Great Stream’, which seems an appropriate name for a river. However, in Roman times it was known as either Bremetena to the Latin speaking invaders or Belisama to the locals.”

“Belisama…. As in Sarah’s father’s surname?” Jenny queried. “That’s interesting.”

“Indeed, it is,” Madame agreed.

They followed the line of the river until they were outside the formal boundaries of the park. There, a row of clean, pleasant looking terraced houses identified by a street sign as the rather obvious ‘Riverside Parade’ rose along the side of the path. The houses were substantially built with three red brick floors, tiled roofs and small front gardens.

They were very nice houses, Jenny thought, houses where somebody with aspirations might keep a maid to do the hard work and live in comfort.

As one of these houses was Sarah Wheaton’s address, she had obviously fallen on her feet by coming north. London’s foundlings were not often so lucky.

As per Jenny’s expectations, a maid in a crisp apron answered the door and showed the two visitors to a well-appointed drawing room with a bay window looking out over the river view. Presently a woman of about thirty years of age came in to greet them.

“But….” Jenny faltered. “Surely, you’re not the Sarah Wheaton we were looking for? Is she your mother?”

“No, I am the person you seek,” she answered. “Though I use my father’s surname, now. I know, I do not look like I am in my late fifties. There is a good reason for that. I should be happy to explain it to you.”

“We didn’t come to ask you for explanations,” Madame told her as they sat and the maid brought mid-morning tea and biscuits for the guests. “We brought you this at your late mother’s request.”

Sarah looked at the suitcase warily at first, then she reached to open it. Jenny craned her neck to see what was inside. She had been curious since the almshouses, but it wasn’t her suitcase to open.

The first thing Sarah took out of the case was an old leather covered bible. It was of good quality and had lasted well despite obviously being read by a woman who really had been of good Christian conduct apart from that one mistake in her past. Wrapped carefully in tissue there was a silk dress that had been fashionable when Prince Albert was alive and young Queen Victoria set the trends. It was proof, Jenny thought, that Mary Wheaton the needlewoman had started out as a girl from a ‘good’ family. Having fallen on hard times she had retained that one reminder of what had once been.

Below that was a velvet bag that clinked curiously as it was picked up. Jenny expected it to contain money, but she was surprised when the contents proved to be silver jewellery of the sort usually found in the British Museum representing the pre-Christian treasures of Britain. There were several brooches and a necklace made of silver strands twisted together as well as rings and bracelets.

“Gifts… from my father,” Sarah Belisama whispered. “He gave me some very like it.”

“They look valuable,” Jenny said. “I wonder why she didn’t sell them when she was in need.”

“Because she never did forget me,” said a deep male voice. A tall, broad man with a grey beard and hair but eyes that seemed curiously young came into the room and sat in a deep armchair. “I thought her dead long ago or I would have sought for her,” he added.

“My father,” Sarah said in formal introduction. “Belisama.”

“Just Belisama?” Jenny asked. “Not Mr Belisama or….”

“Rightfully, it is Lord Belisama, god of the River Ribble,” the man answered. Jenny, who had seen and heard many things in her time was startled by this revelation. Madame less so.

“I had begun to suspect as much when I first heard the story about Sarah receiving a message from the Thames,” she said. Jenny still looked bemused. “It is well known that major rivers have their own gods and goddesses. One of the most notorious is Sabrina, goddess of the Severn. She is known to take watery vengeance on men who do wrong by young women. The Thames is an irascible old man who tends to eschew clothing and frightens old maids and horses from time to time.”

Belisama was respectably dressed on this occasion but admitted to swimming in his river unclothed on quiet summer evenings.

“I was clothed when I met young Mary,” he said. “It was love at first sight… for both of us. She was the daughter of the Dean of St John’s Minster, a good, chaste girl. But we old gods have a way of persuading Christian girls to forget themselves.”

He looked suitably ashamed of that and escaped the wrath of Madame, who knew well what had come of their love affair.

“I didn’t abandon her,” he was quick to say in his defence. “She got frightened when she found out that she was expecting a baby whose father was a pagan god. I wanted to marry her. I would have made her happy. I would have made her a demi-goddess and showered her with tributes. These silver trinkets…. The people who made them many centuries ago threw them in my waters as offerings when men believed in gods like me. I have many more such treasures that I would have given to her. But she was frightened.”

“That is…. quite a lot for a girl to take in,” Jenny was willing to admit. “But you ARE a god. And London surely isn’t so far away. You could have gone after her… persuaded her.”

“No, he couldn’t,” Madame explained. “I don’t suppose Mary knew it. She would have gone to London because it is where anyone goes who doesn’t want to be found easily. But there are strict rules for river gods. They are bound by their hinterlands. They cannot go very far for long. Besides, they tend to be very territorial. Even if Sabrina had let him cross her waters after what he did to Mary, Thames would have flooded Limehouse and Wapping in his rage at a perceived invasion.”

“Exactly so,’ the old god said with a relieved sigh at having his problem explained by somebody else. “All I could do was ask the other rivers to keep a watch for my love. Rivers are notorious places for suicide. The Thames with all its bridges especially so. If Mary had become so desperate, I hoped the Old Man might have had the kindness to take her in his bosom as it were and make her into a goddess of one of his tributaries. We can do that. There is a former shepherd boy I set up to care for the Douglas - down near my estuary where he drowned in 1775.”

“But Mary wasn’t so desperate,” Jenny noted. “She had her baby and placed her with the Foundling Hospital…. Did her best.”

“And it was only when I jumped into the Thames to save that little boy that I was recognised as the daughter of a river,” Sarah added. “It wasn’t until then that I knew who I was. It was quite overwhelming. I think I can understand why my mother was frightened. But I knew I had to find my father. We both thought mother was dead. If we had made inquiries, perhaps we might all have been reunited. But, alas, there is nothing we can do now. I’m glad she had a friend like you at the end.”

“We both are,” Belisama said. “You both have my eternal gratitude. And that truly IS eternal.”

“It is the least I can do,” Madame assured them. Then she mentioned her plan for a headstone on Mary’s grave. Sarah and her father both approved.

“I was born in London, of course,” Sarah pointed out. “I am not tied as father is. I can come down when it is done and see the grave. Perhaps I should visit the Lilies while I am there. I owe them both for much kindness. I hope my ‘eternal youth’ won’t frighten them. It is one of the advantages of being the daughter of a god, as well as the gift of health that Miss Forster saw in me. I shall live a very long life. I shall make sure I do something useful with it. I am thinking at present of joining the council planning committee that wants to build retaining walls just downriver from here. A place called Broadgate is always being flooded. Father does it. I think he might have done it last night. He fell out with the landlord of a public house along there and it is his revenge. But I think I shall have to help them put a stop to that sort of mischief.”

Belisama smiled widely in remembrance of his night’s ‘mischief’.

“It is hardly worthy of a god,” she added. “You should be ashamed of yourself, father.”

Jenny smiled as she saw the way their relationship worked. He was a god, but she was a demi-goddess and she would rein in his excesses like any daughter of an old man with a streak of youthful excess still in him.

Just as it should be.

|

|

|