Rose and Jackie both put their feet up on the two big sofas with the seal of the American President on them – a long story from an old adventure. They had kicked off their high heeled shoes as soon as they got into the TARDIS but were still wearing the glittering dresses they had worn to the gala event on Alpha Centauri.

“Nice people those Centaurians,” Jackie said as Christopher brought tea to them both and then went to help his father pilot the TARDIS home to Earth. “But they don’t half natter on.”

“I don’t mind the natter,” Rose answered. “But I wish their voices weren’t so shrill. Imagine watching a Centaurian soap opera with them all talking like that.”

“The soap operas are fine,” Christopher called out to them with a grin. “But I sat for an afternoon in their parliament yesterday. It was excruciating.”

The Doctor looked up from the navigation console and grimaced at his son, reminding him that he was a diplomat.

“Oh, of course. I would never say such a thing in front of them. But, on the other hand, maybe that’s the problem. Somebody should have told them centuries ago that they’re too squeaky for the average humanoid ear. They might have done something to tone it down.”

He wasn’t being serious, of course. The serious business was concluded before the gala. The Gallifreyan government in exile were now formally linked with Alpha Centauri for diplomatic purposes.

“Oh, I will be glad to get home,” Jackie said with a long sigh.

“For a long time the TARDIS was home for me,” Rose admitted. “But… not so much now. This is our first offworld trip for ages.”

She didn’t mind. She had seen enough of the universe before she and The Doctor were married. Now she was happy to enjoy a lifestyle beyond her wildest dreams and a family life that hadn’t even entered into her dreams until she met The Doctor.

“Ummm….” The Doctor said loud enough to get everybody’s attention. Rose and Jackie looked at him anxiously. It wasn’t the universally bad ‘Uhoh’ which preceded really dangerous stuff like mechanical breakdown or ion storms in the vortex, but it was definitely a forerunner of something they didn’t want to hear.

“Are you really set on getting home soon?” he asked. “Only I’ve had a communication from the Intergalactic Justice Department. They want me to go and try a case.”

“The who want you to what?” Rose asked.

“The Intergalactic Justice Department…. I… sort of signed up to them about half a millennia ago, give or take a century. They provide learned and wise judges in cases that fall outside any particular jurisdiction. I’ve only heard from them twice before. I’d sort of forgotten my membership was still valid.”

“We’re still wondering about the ‘learned and wise’ bit,” Jackie responded. Rose giggled along with her.

“So you’re asking if we want to be dropped off home, first?” she added.

“I could do that,” The Doctor reminded her. “That’s the beauty of having a time machine.”

“Let’s not risk it,” Rose told him. “You might get lost for a half century and come home with a ten foot beard. Besides, I think I’d like to see you looking wise and learned and dispensing justice. That sounds rather cool.”

“I wouldn’t use the word ‘cool’ to describe it,” Christopher added. “But I’m rather curious myself.”

“You can help,” The Doctor told his son. “You’re qualified, too. If the case calls for a sitting justice alongside the presiding judge you’ll do nicely.”

“You’re qualified as a judge?” Jackie asked her husband. “Since when?”

“Two hundred years at school they can be qualified for just about anything,” Rose told her mum. “Anyway, let’s see how they both do.”

The Doctor gave the two women an inscrutable look and set the new co-ordinate. Christopher looked at the destination and then moved to the database console where he found information about the people they were going to meet.

“The Starship Stanislaw Lem is on a twenty-five year deep space voyage transporting the population of an abandoned colony planet to their new home in the Asturian sector,” he said. “The people call themselves the Children of Philemon and five hundred of them had previously established a colony based on strict adherence to biblical teachings, eschewing technology and working with only hand tools to provide food, clothes and shelter. When their colony planet proved tectonically unstable they accepted the offer of transportation to a new world only on the assurance that they would live apart from the ship’s crew, continuing to reject technology.”

“Weird,” Rose commented.

“Very weird,” Jackie added.

“It’s not uncommon,” The Doctor answered. “A lot of Human colonists reject technology and seek some kind of concept of a perfect society. I’ve never quite understood why they think electricity and computers are the reason why the world they left was imperfect, but it’s their choice. Xian Xien is my favourite of these retro-societies. Their new version of China under the system of Mandarin rule is fascinating.”

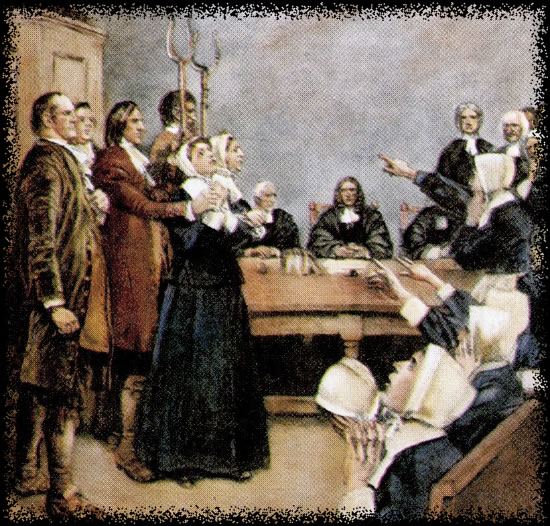

“I agree,” Christopher said. “But I’m not sure about the Children of Philemon.” He reached for the main video screen control. The image of the vortex spinning about the TARDIS was replaced by a still image of a group of Philemons.

Neither Rose nor Jackie were big on history, but the word ‘Puritans’ hung on both their lips. The severe look on both male and female faces, the black coats and hats of the men, the black dresses and white linen aprons, collars and bonnets of the women spoke volumes.

“Why do I get the feeling we’re going to have to dress like that?” Jackie commented.

She was nearly right. As wives of the visiting judges, they were spared the black linen, wearing instead dresses of cool satin, and they had wide brimmed hats with a blue feather in the bands rather than bonnets, but the crisp white linen collar was mandatory, with only a thin band of ornamental lace around the edge to set them apart from the Children of Philemon.

Christopher and The Doctor looked like a pair of conspirators in the Gunpowder Plot in high boots and long coats with tall black hats.

“WHY?” Rose asked as the TARDIS materialised aboard the space cruiser. “I get the idea of living simply, growing their own food, weaving and spinning and all of that, but why do they have to dress like this?”

“They identify strongly with the people of that period of Earth history when these clothes were worn,” Christopher explained. “When they left for their first colony home they thought of themselves like the Pilgrim Fathers who travelled to the Americas to create God-fearing and wholesome communities.”

That answered her question, but Rose was far from satisfied with the clothes or the prospect of meeting the sort of people she disliked the most in her school history books.

They stepped out of the TARDIS and were met by the captain of the ship dressed as a futuristic space captain should – in one-piece stretch fabric with silver piping around the shoulders. He didn’t seem at all surprised by their costumes. He bowed his head in acknowledgement as The Doctor introduced himself and his companions.

“I’ll take you directly to the colony deck. Don’t be startled by how it looks. It has the latest holographic topography installed. They’ve been aboard for five years and have another twenty more to go. The illusion of a normal life on their old world suits them.”

Rose and Jackie weren’t sure what that meant until they stepped through the airlock from an ordinary spaceship corridor into what looked like a cart track leading down a gentle slope towards a small village of grey wood and plasterwork buildings. A church made of grey stone poked its spire up towards a grey sky in the middle of the grey huddle.

“It looks like England,” Rose remarked. “English countryside.”

“That’s what they chose,” Christopher explained. “The deck is about a mile long and three-quarters of a mile wide, but the holographic topography makes it feel much bigger. It’s enough for them to live in the way they lived on their colony world, growing crops, tending animals, spinning, weaving, tanning, cobbling, all of that traditional work.”

“I feel homesick for a telly,” Jackie commented.

“It goes without saying that they don’t have any such thing,” Christopher told him. “These people are the second and third generations since the colonisation so they have always lived without technology. You shouldn’t try to talk to them about that sort of thing.”

“Quite right,” The Doctor confirmed. “And don’t try any women’s lib stuff on these people. The women here know their rightful place is in the home. There’s no discussion to be had about it.”

Rose and Jackie were liking this place less and less the closer they walked towards the village. They stiffened warily as they saw two of the puritan men approaching, dour faces unchanging as they greeted The Doctor and Christopher while ignoring the two women.

“I am the Judge you sent for,” The Doctor said. “You may call me The Doctor. This is my son, Christopher De Lœngbærrow, who will assist me in the work.”

“You are most well come to us,” answered the older of the two men. “I am Samuel Hemmings. This is Gideon Naismith. We are elder councillors. The prisoners are already brought to the council building awaiting your honour’s leisure.”

It was clear that leisure did not come into it. The case was ready to go ahead. The Doctor told the two councilmen to lead on. They headed past the tannery and blacksmiths on the very edge of the village where the smells of those professions were less odious, past the homes and workshops of the spinners and weavers, the potter and other specialist workers.

“Oh!” Rose and Jackie both sighed deeply as they came to the village green and saw a gallows made of newly sawn wood. There was room to hang several people at once on the grim frame. They turned their eyes from it but couldn’t get away from the knowledge that it was connected to the work The Doctor and Christopher came to do.

The council building was beside the church, half stone, half wood, with wide eaves on the tiled roof – the ordinary homes and shops had thatch. They entered up a set of steps and through a wide double door.

Inside, most of the five hundred colonists were waiting for the trial to begin. Every seat in two wide sections with an aisle down the middle was filled with hard faced men. A balcony above was so full of the women in those white bonnets it was clear the Children of Philemon had never heard of ‘health and safety’. Hardier men stood all along both side walls below a long frieze depicting the consequences of sin in lurid detail.

A long table stood on a raised dais at the far end of the hall. A small table was occupied by a young man who waited to record the details of the trial in a large book. Opposite him was a rough bench.

Master Naismith brought two wooden elbow chairs and placed them to one side of the dais for Rose and Jackie before taking his own seat below, next to Master Hemmings. The Doctor and Christopher stood behind the long table. There were water glasses and a jug provided for their refreshment and pens and paper for note taking. There was a heavy, leather bound bible. The Doctor ignored that as he placed his hand over his left heart and gave the oath of the Intergalactic Justice Department which recognised no religion or deity above another, only the supremacy of law and justice.

Christopher did the same before both sat, passing their hats to a steward who hung them on hooks behind them. Meanwhile the defendants were brought out.

The Doctor and his son both looked in astonishment as five women, the youngest perhaps sixteen, the oldest about forty, were lined up in front of the rough bench, chained together hand and foot. They were all barefoot and dressed in rough grey linen shifts tied at the waist with cords. They wore linen caps on their heads but the bailiff snatched them away in the presence of the judges to reveal that all five had their hair shorn in what must have been the roughest haircut in history.

As they stood there, the citizens murmured loudly and there were shrieks and cries of distress from the balcony. The Doctor rapped on the table in front of him and called for silence. The bailiff repeated his order though unnecessarily. It was already being obeyed as quickly as five hundred individuals making separate noises could quieten themselves.

The Doctor turned to look at the defendants. Four of the women looked down at the floor sorrowfully. The eldest met the gaze of the authoritative stranger who sat in judgement over them with a stubborn and proud expression before a slap from the bailiff forced her to drop her eyes, too.

“That isn’t necessary,” Christopher told him. “Nor, surely, are the chains.”

“These are evil women,” the bailiff replied. “They must be dealt with firmly.”

“Let us hear the charge,” The Doctor said, cutting off the possibility of a lengthy discussion of prisoner treatment. The bailiff stood to attention and read from a sheet of parchment.

“The charge is that these five women, Elizabeth Brownell, Jane Worthing, Judith Worthing, Mary Elizabeth Acres and Anne Mary Acres, did cause the death of Reverend Enoch Waring, vicar of this parish, by means of witchcraft,” he pronounced.

“Witchcraft?” The Doctor began to rise from his seat then sat down again.

Perhaps he ought to have guessed. A puritanical obsession with godliness often came with an obsession with rooting out ‘evil’ that was, inevitably, to be found in the simplest of actions or words.

“Let us hear the evidence for the prosecution,” he commanded.

“My Lord?” The Bailiff looked confused. There was more murmuring in the hall. Gideon Naismith approached the judge’s table and leaned close to speak to The Doctor.

“Sir, you have misunderstood. The confessions of these evil women have already been obtained. They are set before you. We merely need a man of authority to confirm the guilt of the miscreants and pronounce the sentence of death.”

“YOU misunderstand,” The Doctor replied. He stood up so abruptly it was a few seconds before Christopher joined him. He spoke to the whole room, not only to Master Naismith. “You asked for a Judge from the Intergalactic Justice Department. We are not accustomed to being presented with faits accomplis. Everybody sit down – Master Naismith, return to your place. Bailiff, allow the women to sit and then take your own seat. Everyone be silent until I have read these ‘confessions’ and then I will decide how we are going to proceed from here.”

The murmuring people silenced immediately, agog to see what would happen. Master Naismith stared in astonishment at the great and learned judge and seemed about to argue, but he met The Doctor’s eyes full on. No further word passed between them, but Master Naismith, an elder of the town, used to having his word obeyed, seemed to diminish in stature and self-assurance before those steely grey eyes.

“Your will be done, my lord,” he answered at last and returned to his chair beside the dais. The Doctor and Christopher both sat and turned the pages of the folio in front of them. They discovered several pages of confessions, all in the same handwriting, since they were records of an oral discourse, signed and witnessed by either Naismith or Hemmings, or in the case of Elizabeth Brownell, both.

They read quickly, but not as quickly as they might have done with their natural Time Lord ability to scan a page and take in its entire text in seconds. They didn’t want to end up accused of witchcraft themselves.

“This is the evidence?” Christopher asked telepathically. “Accusation, followed by forced confessions? Nothing tangible at all?”

“Just what I was thinking,” The Doctor replied, taking care not to look at his son too intently. He came to the last page and then sat back in his chair, thinking carefully, scanning the faces of the citizens who sat expectantly, glancing once at Rose as she quietly leaned forward and took the sheaf of confessions for her and Jackie to read for themselves. Their only experience of a courtroom was a box set of Law and Order UK DVDs, but they knew this was not how it was supposed to be.

Masters Hemmings and Naismith were frowning deeply. They had expected a quick, simple proceeding, but now they didn’t know what was going to happen. Even the clerk looked uncertain. He had expected a quick set of notes on the sentencing, but now it looked as if he was going to have to do a lot more work. He quickly sharpened a new quill and opened a fresh pot of ink.

The five women were as perplexed as anyone else. They, too, had expected a quick pronouncement and an even quicker execution out there on that newly built gallows. They looked tired and uncertain. Did this new development only prolong their inevitable end?

That depended on a great deal, as The Doctor knew full well. It was possible that they WERE guilty. In that case, he could pronounce them so and let them be punished accordingly. But if they were innocent victims of a literal witch-hunt, then it was his duty to find the truth.

“Master Nasmith, by what method of torture were these confessions extracted from the accused?” he asked after the silence began to be too much and murmurings and whispers were beginning again. They quickly ended as the people listened once more.

“Torture?” Master Naismith looked as if he had never heard of the word before.

“You heard me. Clearly some means of coercion was used. What was it?”

“No coercion, sir, only tests to prove the demonic possession of their souls. All five were swum….”

“Swum?” The Doctor knew full well what the word meant – the women, bound hand and foot, would be thrown into a pond or river, whatever was available, to see if they sank or floated. The latter was proof of guilt since honest souls would sink.

“Swum, my lord. It is a commonly used method of proving the guilt of a witch.”

“They were wearing these linen shifts I see them in here when they were plunged into the water?”

“My Lord?”

“It was a simple question. What were the women wearing when they were swum?”

“These are the clothes of shamed jezebels, to mark them out from the goodly. When they were swum they were still wearing the clothes of respectable women – such as you see among the citizens of our townland.”

“Yes, I see. Wide skirts that would hold enough air within their folds to provide buoyancy for many minutes. And you took that as proof that the devil was holding them aloft, rather than a matter of physics. This method has been disproved many times and is not held as a valid proof. Nor is any confession given by a woman who survives such a torture held to be sound. What other evidence is there?”

“When the woman Brownell, chief of the witches, was brought to the chamber within which the body of the Reverend Waring was lain, the body bled from the eyes and mouth. She then fell into hysterical laughter whereupon she had to be restrained physically and a gag placed in her mouth.”

“Really?” Christopher’s eyes arched and he looked at his father.

“By the description of Reverend Waring’s physical condition I see here,” The Doctor said slowly. “I should think he had a coronary heart attack. Post-mortem bleeding can occur due to the pressure of blood in the head once circulation has ceased. If the head was moved after resting for some time, it is even more likely to occur. Was the head moved?”

“Master Hemmings turned it in order to let him face the accused,” Master Naismith answered.

“There you go, physics over superstition yet again. I am throwing out the evidence of the bloodshed, and any confession made AFTER the women were swum. Now bring forward witnesses to give sworn testimony for the prosecution. After a lunch time adjournment I will hear evidence for the defence. If necessary we will continue tomorrow.”

Master Hemmings and Master Naismith talked between each other quietly, and then called Mistress Martha Naismith, wife of the Elder, to tell what she knew of the events leading up to the death of the vicar.

“It was a little after the tenth hour of morning, on Tuesday last. I was bringing a newly made cheese to my mother, who lives on the south side of the village. I saw that brazen woman, Elizabeth Brownell, hastening from the presbytery. She saw me and paused in her step, then walked away in the opposite direction.”

“Is that all?” The Doctor asked. “You saw Elizabeth Brownell hurrying from the house? You heard no word spoken by her, nothing from the Reverend?”

“No word. But her visage was black as thunder and I feared to catch her eye lest her anger be upon me.”

“That is very little evidence with which to make an accusation of witchcraft.”

“There is more. Elizabeth Brownell went to her own house, where the other four waited, and it was only a little time afterwards that Reverend Waring died. Clearly they conjured spirits together to bring him to his doom.”

“Objection,” Jackie proclaimed loudly. “That is supposition. The witness cannot possibly know what they were doing inside the house.”

“Objection sustained,” The Doctor replied, impressed by Jackie’s impression of a defence counsel. “Please stick to what you know to be a fact, Mistress Naismith. What happened to Reverend Waring? Did you witness his death?”

“I did, sir. He came from the presbytery about an hour later as I was coming from my mother’s home. He looked angry. He was walking towards the Brownell house, when he stumbled in his step, clutching at his heart, and then fell. He writhed on the ground as if in a fit, and then was still. The blacksmith, Master Collings, came to his assistance. He sent his apprentice to fetch doctor Rowan, but it was too late. The Reverend was dead, by the wicked forces of those evil women.”

The Doctor glanced at Jackie and winked, forestalling her fresh objection.

“Mistress, again I must warn you not to present supposition as evidence. You saw the Reverend fall to the ground and two good citizens come to his assistance. That much I accept as true witness, but I cannot allow you to make judgements about the cause of death.”

Mistress Naismith looked suitably chastised.

“What happened next?” The Doctor asked. Mistress Naismith admitted that she knew no more. She had hastened home and told the news to her husband.

The Doctor told Mistress Naismith to stand down and called her husband to give his own evidence. He was solemnly sworn upon the big bible and then stood to give his evidence.

“When my good wife told me what had happened I went at once to the presbytery. By that time the men had brought the Reverend back to the presbytery and the good Doctor Rowan had confirmed death by apoplexy.”

“The Reverend was seventy years old, I notice,” Christopher said. “Men of that age are prone to heart attacks and other failings. Why did you suspect witchcraft?”

“Because my good wife mentioned that the Brownell woman had gone from the presbytery not an hour before the death of the Reverend. There had obviously been something between them. Master Hemmings and I went to the house to question Brownell and found all five women there, clearly guilty of some act of mischief. The house was searched and evidence found that pointed to their nefarious actions. The women were arrested and tested for further proof – but that has been dismissed by you, My Lord.”

“WHAT evidence was found in the house of Elizabeth Brownell?” The Doctor asked. The question appeared to surprise Naismith. It really didn’t seem to have occurred to him that anything other than the confessions of the five women were necessary to convict them.

“Dolls,” he answered.

“Dolls?” Christopher echoed the word curiously. “How are dolls anything to do with murder?”

“I think I know,” The Doctor replied to him telepathically. “If that’s what went on, then it may be that the women are guilty, after all. But let us see what transpires.”

He looked squarely at Naismith who flinched under his gaze.

“Bring the dolls to the courtroom,” he said. “I want to see them for myself before they are accepted as evidence.”

Master Naismith sent a strong lad to fetch the evidence. Meanwhile The Doctor watched the accused women. This new element in the trial was worrying them – especially the youngest, Anne-Mary Acres. She looked close to fainting as a large box was brought into the court – a box full of dolls. Christopher reached for the carafe of water and poured a glass before bringing it to the girl. She drank gratefully. The others looked on with something like envy.

“Bailiff,” Christopher called. “When did the women last have any food or drink?”

“They had bread and water at daybreak,” the Bailiff replied. It was nearly midday by the clock high on the back wall of the warm room. Christopher glanced around at the expectant faces of people who had eaten well and then come to watch the proceedings as a grim sort of diversion from the ordinary routine of daily life. He turned and spoke quietly to his father, who nodded in agreement.

“We shall adjourn for an hour for refreshment,” The Doctor said. “That will give me time to examine this evidence, and for the prisoners to rest. The court shall now rise.” He and Christopher stood. The five accused women stood. The rest of the citizenry were a beat behind, caught out by his abrupt command.

The Doctor turned to the Bailiff as he went to lead the defendants out of the court.

“Where are these women being held during these proceedings?”

“In the crypt of the church, sir,” the man answered. “It has but one entrance and a solid lock upon it, making it impossible for all but the devil to bring about their escape.”

“Is it dry and warm? Do they have straw to lie upon? What food and drink have they had?”

“It is dry, though being somewhat in the shade it is cool regardless of outside climate,” the Bailiff responded. “There is straw and they were given cloaks to cover them. They had a portion of bread and water at daybreak.”

“Give them more bread – fresh bread, not stale scraps from yesterday - and something substantial – cheese or meat – and buttermilk. I will ask them later if it was done.”

“Yes, my lord,” the Bailiff said. Kindness to accused witches was a startling notion, but he had no intention of disobeying an order from a man who seemed to look into his soul.

When the women were gone, Master Hemmings escorted The Doctor and Christopher along with their wives to a room at the back of the hall where his wife, Anne Hemmings, served the honoured guests a good luncheon. There was a meat pie, cuts of roast fowl, cheese, butter and bread, as well as a cherry pie and thick cream for dessert.

“There was a fine crop of cherries in the garden this year,” Mistress Hemmings said when The Doctor praised her baking. “I have a dozen pies made to share with my neighbours.”

“What about giving one to those women in the crypt?” Jackie suggested. “It doesn’t sound like they’re having much of a meal.”

“Give my pies, baked by my own hand, with flour milled by a goodly man, to women such as they?” Mistress Hemmings was shocked at the idea.

“Isn’t that the sort of thing goodly people should do?” Rose asked. “Give kindness to the less fortunate. Whatever else they are, they’re certainly THAT.”

If she had just been Rose Tyler of the Powell Estate, she doubted if anyone would have taken notice of her. But she was the wife of the learned and wise judge, wearing a satin gown. Mistress Hemmings looked on her as one of her betters. She nodded as if she had been given some hitherto unheard of wisdom.

“Indeed, it is a Christian virtue,” she admitted. “But my good man has forbidden anyone in the townland to have discourse with the women. I could not be seen going over there.”

“I’ll go,” Jackie responded with something of the fierceness that comes of being a single mother in a London council flat. “Put a cover over the pie and I’ll take it.”

“I’ll come with you,” Christopher at once announced. He wasn’t sure what danger she might be in. Certainly he was not concerned about his wife being bewitched, but he wanted to look after her all the same.

“Christopher, remember, you should not have discourse with them, either,” The Doctor said. “You should not even go into the crypt where they are. It might prejudice the case if you speak to them outside of the courtroom and the bounds of oath.”

“Of course,” Christopher answered. “I shall bear that in mind.”

When they were gone, and Mistress Hemmings had taken the empty plates to be washed, The Doctor turned to the box of dolls that were such a key part of the evidence against the women. Rose looked, too.

“These are just dolls,” she said, picking up a very finely made rag doll with carefully embroidered features. “Children’s toys.”

“Those are,” The Doctor remarked, placing half a dozen such pretty things aside. He wondered if they were too frivolous for the children of these hard-nosed puritans. Making such things probably constituted a waste of God-given time when there was real work to be done.

But time-wasting wasn’t the same as witchcraft. The Doctor picked up another doll that lay beneath the colourful toys and examined it carefully.

“It’s Hemmings,” Rose commented as he held up the black-clad rag doll. It was a caricature of Master Hemmings, the dour Elder townsman.

“And this one is Master Naismith,” The Doctor added as he held up another of the dolls. They were similar enough in their dress, but with a few clever stitches the faces had been made to resemble in a comic way the two Elders.

“I recognise this one, too,” Rose said. “This man was sitting next to Naismith in court. I don’t know his name, but I think he’s an Elder, too.”

“I don’t recognise this one, but I’m guessing it’s the late Reverend Waring.”

The doll The Doctor held up was fat in the way that older men who eat too much and exercise too little are fat rather than the plump healthiness that one of the baby-faced dolls resembled. The face was reddish-purple from the same ill-use and the eyes bulging.

“If that’s what his doll looks like I’m glad I never met the real man,” Rose commented. “He looks like a toad.”

“Lady!” Mistress Hemmings had stayed quiet, but now she could not restrain herself. “Madam, you cannot speak so of a goodly dead man.”

“I can say what I like about anyone,” Rose answered. “How do I know he’s ‘goodly’? He looks like he’s eaten more than his fair share of the pies. Isn’t greed one of your deadly sins? I’ve heard about plenty of vicars who didn’t practice what they preach. Maybe he was one of them.”

Mistress Hemmings was scandalised. This was the wife of the learned judge speaking, her social superior, but even so, her words sounded close to blasphemous.

But before she could comment about that, Jackie arrived back, her face set in that expression even The Doctor was a little scared of, declaring that these women were no more witches than she was.

“That’s not a good thing to declare around these parts,” The Doctor told her. “You might just end up sitting next to them in a linen shift and a bad haircut.”

“Don’t get funny with me,” Jackie responded. “You ought to see them. You ought to talk to them. Four of them are just girls. The eldest is Rose’s age. The youngest is just a kid. The other two… well they’re the same age I was when I married Pete… the same age Rose was when you took her away with you. They’re not even old enough to have done anything evil. But I reckon something evil has been done to them.”

“Madam!” Mistress Hemmings was shocked. “That is no way to talk to your betters.”

“My betters?” Jackie looked at the woman of the house curiously. “What do you mean by that?”

“She means men,” Rose answered. “We’re just women. We should be quiet and dutiful in front of our men.”

Jackie looked about to use the sort of words that would be used among the women of the Powell Estate if anyone had suggested that they should be dutiful towards men, but she glanced down at the floor-length satin dress she was wearing just in time and remembered who she was, now.

“Who but a witch would make a thing like THIS?” Mistress Hemmings demanded, forgetting her place for a moment as she thrust the effigy of Reverend Waring into Jackie’s hands.

“Jim Henson?” Jackie replied as she turned the doll around and looked at its florid face. “Or maybe the guys who did Spitting Image.” Rose and The Doctor both grinned, recognising the cultural references. Christopher may have done, too, but he didn’t see the funny side.

“It is a witches tool, used to cast a spell upon a man,” Mistress Hemmings said. “Pins thrust into the heart of the doll would cause apoplexy in the victim.”

“Rubbish,” Jackie answered her. As she spoke, she was still turning the doll around and examining the stitching of the seams, the embroidery that formed the face, prodding the fat stomach to work out what sort of material filled it. Rose was the only one who noticed her pull something from the fabric and conceal it in her pocket.

“Christopher, this is what I mean,” she added. “All this talk about dolls and pins. Somebody needs to talk to them before this gets completely out of hand.”

“Jackie,” Christopher answered in a quiet and patient tone. “Neither of us… neither father nor I, can talk to those women. That is what I was trying to tell you. We have to be impartial. We have to give judgement based only on what we hear inside the courtroom. We can’t even listen in on their prayers. Anything that would prejudice the case….”

“That is exactly what the word prejudice means, you know,” The Doctor told her. “To pre-judge something and therefore not be of an open mind.”

“I don’t need lessons in entomology from you,” Jackie responded sharply.

Christopher looked as if he was about to point out that she meant etymology, the origin and meaning of words, not the study of insect life. The Doctor flashed a look at him and he changed his mind.

“Who is going to speak for the women when we get back into that courtroom?” Jackie asked, passing over the incident for now, but no doubt planning to punish Christopher later, in private.

The Doctor looked at Mistress Hemmings for the answer to that question. The wife of the Elder was perplexed. She knew nobody who would speak up for witches among the goodly people of the townland.

“If I hear the word ‘goodly’ mentioned about anyone who doesn’t have all their scouting badges and a good conduct letter from their headmaster, I am going to slap them,” Rose said. Jackie said nothing, but that dangerous expression hardened on her face and even The Doctor wasn’t sure what was going to happen when he re-opened the proceedings.

Nor were the Children of Philemon who gathered to see what would transpire. There were even more of them than before. Many men stood around the side walls. The gallery was packed with women and even some children.

And they were all as surprised as The Doctor and Christopher were when Jackie stood and announced that she was acting as counsel for the accused.

“That cannot be so,” protested Master Naismith. “She is a woman.”

“You don’t say,” Jackie answered sarcastically.

“There is nothing in the rules of the Intergalactic Justice Department that holds a woman from the Bar,” The Doctor said. “It will have no bearing on my eventual judgement of the matter. Sit down, Master Naismith, and let us proceed.”

Master Naismith had no choice but to do as he was told. Jackie remained standing and called for Elizabeth Brownell to stand up. The Doctor asked her to say the oath on the bible. She did so. The Doctor and Christopher were probably the only ones, with their Gallifreyan hearing, who knew that Master Hemmings had murmured in astonishment at a witch being able to touch the Bible without bursting in flames or that she could speak the name of God without her tongue cleaving to her mouth.

“Elizabeth,” Jackie said. “Are you married?”

“I am widowed, madam – these past ten years. My husband died before we began our journey to the new world.”

“So how do you make a living?”

“I am a seamstress,” she replied.

“You mean you sew clothes?” Jackie queried. She came from working class London. She knew that ‘seamstress’ was a title with a double meaning. Elizabeth Brownell obviously knew that, too.

“I make clothes, yes,” she said. “These girls are my apprentices. They are all orphans and they were bound to the trade. That is the only reason they were in my home on the day that the Reverend died. It is the reason they were arrested along with me.”

“Do you also make dolls?” Jackie waved the caricature of Reverend Waring in the air.

“Making toys is practice for the girls,” Elizabeth answered. “The different stitches used to make a doll are later employed in the making of strong seams for winter coats.”

“Makes sense to me,” Jackie conceded. “This is a very well made doll, I must say. Did you make it?”

Elizabeth paused before answering. She was standing forward from the bench so she couldn’t see the faces of her apprentices and fellow accused as she began to answer in the affirmative. She didn’t see the youngest, Mary-Anne Acres, stand up on shaky legs.

“I made it, madam,” she said. “I made all of the dolls that look like people. It… it was an amusement, only, madam. I meant no harm or… or disrespect.”

“I think you probably meant a LOT of disrespect,” Jackie told her with a smile just starting at the side of her mouth. “But sit down again for a minute. You’ve not sworn the oath and anything you’ve said shouldn’t be on the record, yet.”

Mary-Anne sat down. Jackie spoke again to Elizabeth.

“You let the girls make these dolls – using pins and needles.”

“Yes, madam,” Elizabeth answered. “It is not possible to sew anything without pins and needles.”

“That’s true enough.” Jackie put down the effigy of Reverend Waring and picked up the two made to look like Masters Hemmings and Naismith. There were some muffled giggles from up in the balcony and scandalised glances upwards from the body of the hall. “When these were being made, a needle must have gone through the fabric lots of times. Yet no harm came to those two men who were being caricatured? They’re both alive and well and have no holes in their bodies?”

“No, madam,” Elizabeth answered. “But I don’t see….”

“Sticking pins into a doll doesn’t make a man drop dead, is my point,” Jackie answered. “I’ll prove it right now, if you like. Master Naismith, are you feeling well? Remember you’re in a courtroom, and as an Elder you should tell the truth. ”

“I… am, madam,” he answered. “But I don’t understand….”

Jackie put down the Hemmings effigy and held the other one higher. She pulled a long sewing needle out of the doll’s head. There were some gasps around the room and a quizzical expression from The Doctor.

“I think one of the girls mistook your head for their pincushion,” Jackie said. “But you already stated in this court, in front of us all, that you feel perfectly well. I think that proves that all this doll stuff is nonsense, don’t you, MY LORD?”

She turned to The Doctor who nodded and smiled warmly at her. He had hoped to find some way of disproving this sort of nonsense in the same way he had already disproved the ‘swimming’ and the ‘bleeding corpse’ methods of detecting a witch. Jackie had done it for him.

“The ‘evidence’ of the dolls is dismissed,” The Doctor said. “I am also, at this stage, dismissing any charges laid against the four apprentices. I see absolutely no reason to suspect them of anything. Mistress Acres, it is not wise to be disrespectful to your elders. Stick to making baby dolls with dimpled faces in future. That is my formal warning to you as a Justice.”

“Yes, sir,” Mary-Anne answered.

“Mistress Hemmings,” The Doctor said, looking at the housewife who was so famed for her pies. “Take these four innocent women and put them in proper clothes, then see that they have a proper meal and a place to sleep now that their ordeal is over.”

That much was done, then The Doctor called the court to order again.

“I am, in fact, dismissing all charges of witchcraft. There is a doubt, yet, about whether anything passed between Elizabeth Brownell and the Reverend that may have contributed to the death of the latter. Jackie, you may resume your seat. I will deal with this last matter. My thanks for your efforts thus far.”

Jackie sat, just a little relieved that she didn’t have to pretend to be a lawyer any more. The Doctor bid Elizabeth step closer to the table.

“What was the cause of argument between you and the Reverend Waring?” he asked. “Please don’t fear anyone’s judgement. Just tell me what happened.”

“He wanted Mary-Anne to be a chorister in the church,” Elizabeth answered. “I went to tell him she would not be.”

“What is wrong with being a chorister?” Christopher asked. “Does Mary-Anne have a good voice as well as an eye for caricature and skill with a needle?”

“She does. But Reverend Waring never cared about that when he chose girls to be in the choir.”

“I don’t follow,” Christopher said, though the glance that passed between him and his wife proved that he did.

“Dig down a little further than the graves are dug around here, and you find metal – the floor of the ship we travel in,” Elizabeth said. “A mere appearance of God’s countryside. The same is true of many of the people here. Dig beneath the surface and they are not so fine and upstanding as they seem.”

“The cup and platter,” The Doctor said. “There is a biblical quote, is there not?”

“Thou blind Pharisee, cleanse first that which is within the cup and platter, that the outside of them may be clean also,” Elizabeth answered promptly. Again The Doctor heard Master Hemmings gasp under his breath and utter a whispered surprise that a woman he had thought to be evil could quote the Bible so easily.

“The gospel according to Matthew, Chapter twenty-three, verse twenty-six,” Master Naismith added, proving that he was familiar with the Good Word, too.

“Indeed,” The Doctor said. “You understand what is implied in that simile?”

“That things are not what they may seem on the surface?” Master Naismith replied. “We all know that this place we are living in is but a simulacrum. We are in no illusion about that. But….”

“It is not just the soil that hides a falsehood,” Elizabeth Brownell continued, even though she had been given no leave to speak. “Reverend Waring made improper advances to me when I was Mary-Anne’s age. I was so ashamed I did not dare speak up, even if I thought I would be believed. He has done the same to others. When he tried the same with Mary-Anne, an orphaned girl with nobody else to turn to but me, I could bear the hypocrisy no longer. I went to the presbytery and told the old lecher what I thought of him. I said I would tell every woman in the townland of him, and that they would tell their husbands. He begged me to hold my tongue, but I refused. He knew I could expose him, and I fully meant to. God punished him with death before I had a chance to expose him. He escaped the punishment of men. That is why… when they dragged me to the presbytery on the word of that gossip, Martha Hemmings, I laughed. Wouldn’t any woman who was cheated of justice in such a way? Then the Elders cried ‘witch’. They ransacked my home, and arrested four innocent girls as well as myself. I told Master Naismith the truth, but he slapped my face and called me a harlot and a witch. He said that nobody would believe my word against that of a goodly man who was gone to his grave!”

“Believe it!” cried a voice from the gallery. Every eye turned to the women, but which one spoke first, nobody was certain. Within five minutes, though, four women of different ages came down into the hall and swore on oath that they had been propositioned by the vicar.

“Masters Naismith and Hemmings,” The Doctor said when that was done. “I will hold you responsible for cleaning the cup and platter of your community. Perhaps you will all be better for it. As for the case in question, Mistress Brownell was not present when the Reverend, fearing his secret indiscretions were about to be uncovered, suffered his fatal heart attack. No charge of witchcraft can be made. Therefore, I am bound to find her innocent of all charges.”

Nobody raised any voice of opposition. In the gallery a few voices were raised to applaud his decision. Nobody dared to quieten them.

“Mistress Brownell, go and join your apprentices, wherever they are, and put all of this behind you.” He said that aloud and then lowered his voice and spoke to her privately. “Try not to hold any grudges against the people who were so quick to point fingers. But if they start to forget the lessons learnt here, don’t be slow to remind them.”

“Thank you, sir,” she said. She turned and walked down the front of the dais and along the central aisle, past all of those men who had been so quick to point those fingers. Some of them looked her in the eye, some of them looked away. The Doctor watched and felt that Elizabeth Brownell would find her own way of dealing with them.

“Come on,” he said to his own family. “Let’s get out of here. Time to go home.”

Christopher stopped long enough to speak to the long-suffering young man who had written down every word spoken and even deleted those parts ruled out of order, then he took Jackie’s arm and walked with her. The Doctor took Rose’s hand as they left the courtroom and stepped out into the artificial sunshine of the holographic topography. A discordant sound made them look around. It was somebody sawing through the uprights of the gallows. Rose turned from the sight. She still didn’t want to look at it.

“You were great,” she told The Doctor when they were back in the TARDIS and on their way home, finally, with strict instructions from Jackie not to stop off anywhere else unless it was the actual Titanic sending out an SOS.

“Don’t even start on that one,” The Doctor answered her. “But on the subject of great work, you were fantastic, Jackie. Law and Order ought to snap you up right now.”

Jackie grinned widely at the rare praise from The Doctor.

“That was a really great trick with the needle. Where did you come by one at such a handy moment?”

“I pulled it out of that ugly fat doll earlier,” she answered. “It was stuck through the belly.”

The Doctor stared at Jackie. So did Rose.

“Wait a minute, doesn’t that mean that one of the girls COULD have used the doll for that voodoo thing?” she asked. “The doll for the vicar had a needle in it….”

“But that’s all rubbish,” Jackie sad. “That’s why I knew nothing would come of sticking it in the head of the other doll right in front of the old fool.”

“I don’t know,” The Doctor replied. “This is a big universe. I’ve heard of people being controlled by spots of their blood, a hair with their DNA in the follicle, a tooth, a nail clipping. With the right form of words to generate a control field just about anything is possible.”

“But surely those poor women don’t know about that sort of thing?” Rose queried.

“I don’t care if they did,” Jackie protested. “That man was revolting and I don’t think much of the rest of that lot. He got what’s coming to him and those women deserve better in the future.”

“It might not be justice as laid out in the Intergalactic Justice Department rulebooks,” Christopher added. “But I think I agree with Jackie.”

“So do I,” The Doctor agreed. “But don’t get used to that happening. This is not a legal precedent for agreeing with my mother-in-law!”

|

|

|