Marie attracted The Doctor’s attention and pointed to a highlighted section of a news article on the TARDIS’s information screen. He read dutifully.

“… star Trappist-1 in Aquarius constellation. Six of the planets orbit in a temperate zone where surface temperatures range from thirty-two to two hundred and twelve degrees Fahrenheit. Three of the planets are believed to be potentially habitable and could have water, greatly increasing their chances of life….”

He looked up at Marie quizzically.

“NASA just discovered them with long range radio telescopes and whatsits. Six Earth-like planets orbiting one sun. It’s a really big deal.”

“You know, Human exploration of space was a lot like the early exploration of distant parts of Earth. The discovery of those parts came as no surprise to the people who lived there and knew exactly where the places were.”

“You mean there were already people on those planets?”

“Why wouldn’t there be?” The Doctor asked. “Those are the optimum conditions for life. Why wouldn’t it have evolved there?”

“Well, if you’re asking,” Marie replied. “According to my catechism teacher God made Heaven and Earth and put mankind upon the Earth, no mention of other worlds. But I know better than that, now, and you are perfectly right. There could easily have been people on those worlds. So what are they like? Are they like us, or more like green, bug eyed….”

“Actually, I have no idea,” The Doctor responded. “Trouble is, HUMANS called the system Trappist-I, because they studied it using the Transiting Planets and Planetesimals Small Telescope at the La Silla Observatory in Chile and made up the acronym Trappist from that.”

“Nothing to do with Trappist monks, then?”

“Nothing at all. Besides, that isn’t what the rest of the universe calls it. The rest of the universe doesn’t even call the constellation ‘Aquarius’. Why would they, after all? It was your Human ancestors that assigned those romantic and fanciful names to the Heavens.”

“What do the Time Lords call the Constellation of Aquarius?” Marie asked.

“Omega’s Dust Storm. Or in the star charts, 0065-54-65 from Galactic Central. Earth, by the way is called Sol Three, Mutters Spiral. That’s the Milky Way from the other end.”

“So, what you’re saying is you can’t take me to Trappist-I?”

“I didn’t say that, just that I’m going to have to look the place up in the TARDIS database.”

“Well, if it is any help, NASA have the co-ordinate on their website.”

The Doctor gave a sly smile. Marie had a feeling he knew perfectly well how to get to those planets. He was just teasing her in his usual way.

“There, what did I tell you,” he said after a while. “The planet is known to the rest of the universe as Allassabi. In a local dialect that means Bad Smell.”

They had landed on the planet while he was talking. But they weren’t going on a country walk. Even a glance at the dismal view on the screen was enough. The Doctor reached into a cupboard beneath the console. He handed Marie a plastic mask for her mouth and nose, the sort people in Tokyo and other badly polluted cities invariably used. He groped in the cupboard again and found a pair of wrap around goggles. He, himself, donned his ‘sonic glasses’ that made him look like an aged rock star at Glastonbury. Marie looked at the mask and goggles and put them on, hoping The Doctor wasn’t playing some joke on her. She knew she must have looked ridiculous.

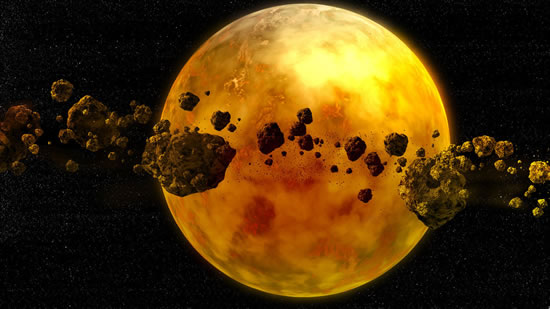

They stepped out of the TARDIS and she realised the face accessories were very necessary. The sky was an ugly yellow colour like a huge nicotine stain. The air itself was thick with a similar coloured haze. Through the mask Marie could taste something bitter and nasty. Without the goggles she knew her eyes would be watering.

The source of the haze was a huge lake. She hesitated to call it ‘fresh water’. It was muddy yellow and she couldn’t imagine anything living in the opaque depths, even though suspicious bubbles rose up from time to time. The haze meant that she could only just make out the far shore and it was a dismal prospect.

Within the limited view there was some sparse vegetation in patches here and there but mostly there was just hard packed soil, and everything was coated in yellow dust.

“Yuck,” Marie commented, though her one-word appraisal was muffled by the face mask.

“I used to know another lady who used that word a lot,” The Doctor answered. He had planned to recycle his breathing, but the air burned his throat even without taking it into his lungs. He pulled a large red handkerchief from his pocket and tied it around his mouth. He looked like an aging rock star crossed with a dandy highwayman, but at least he could breathe through the fabric.

“You took her to places like this, too?” Marie asked.

“No… she was talking about my sense of fashion,” The Doctor admitted. He was going to make another remark, but Marie suddenly screamed. Since that wasn’t something she often did, he was startled enough to look at what had upset her.

It was a body, sprawled near the edge of the rancid lake. It looked like a slightly overweight middle aged man – human by all appearances. It wasn’t completely certain because the head was missing. Marie stepped back as The Doctor knelt to look closer.

“The neck was severed in one sweep,” he confirmed. “As if by a large pair of scissors. About an hour ago judging by the near complete exsanguination.”

“I’m not sure I needed to know that,” Marie said weakly. She was not the swooning type like some silent movie heroine, but she had never actually seen a headless body before. The amount of blood forming a darker patch of pollution near the edge of the lake was sickening.

The Doctor quickly checked the dead man’s clothes. They were dark orange overalls of a workmanlike sort. An identity card in the top pocket matched an embroidered label on the pocket itself.

“His name is Monk,” The Doctor confirmed. “Paul Monk. He’s a gas supervisor for a company called ‘Transcore.”

“I’m not sure I needed to know that, either,” Marie added. “I suppose we’d better find somebody to come and get him.... This Transcore must have a local office?”

She looked around, wondering if there WAS anyone on this uninviting planet to whom they could report the murder.

Was it murder? It had to be, she supposed. Nobody ever accidentally cut their own head off.

And where WAS the head, for that matter?

“I think there’s a building on the other side of the lake,” The Doctor said after squinting into the haze and adjusting the sonic glasses a couple of times. “We… could look around for a boat.”

Marie looked again at the gurgling miasma that passed for water and dismissed an unbidden memory of a disaster movie with an acidic lake eating through an outboard motor. Even though it seemed a long, dull walk around the lake it was decidedly the better option.

They walked.

It was no afternoon stroll. The thick, chemical filled air did nothing for the lungs even with a face mask. A stand of very sick trees resolved themselves at one point. It was hard to imagine how they ever drew enough nutrient from the unpromising ground to grow to any height.

“Did we… humans… make this planet into such a mess?” Marie asked. “Surely we should have learnt our lesson by the time we could reach somewhere like this. I mean, the rainforests, the Aral Sea, ozone layers… did we come across the universe and do it all again?”

“I’m really not sure,” The Doctor answered. He pulled his sonic screwdriver from his pocket and fiddled with it before examining the tiny readout on the side. “Maybe not. The yellow stuff seems to be a natural gas formed under the crust. There must be a weak spot under the lake where it bubbles up. I think this place has always been this Sylvanian paradise.”

“Well… in that case… why did humans come here, them?” Marie asked. “There are SO many better places to go. Even on Trenzalore with three hours of daylight people could walk around without face masks.”

“That really is a good question. Perhaps we’ll find out in there.”

Marie wasn’t sure at first where he was pointing. Then she started to see a shape in the haze. As they walked it began to loom sinisterly. For a building to loom took a certain kind of atmosphere. This place had it. Slowly the basic shape resolved into something that couldn’t be anything other than an industrial plant. It was built mostly of iron red panels with chrome ribs. Huge pipes and conduits came out of a silo at one end and snaked down the wall, across the ground and into the lake. Whether they were taking something out of the lake or pumping something in wasn’t quite clear.

The word ‘Transcore’ was fixed in huge letters across the side of the silo.

The Doctor marched up to a wide doorway with a smaller ‘postern’ door set into it. He knocked hard and a man in the orange overalls with the company logo on it answered his summons. He presented his psychic paper as credentials. He also showed the dead man’s identification and pointed back across the haze covered lake. The doorman immediately called for a team to investigate.

Meanwhile The Doctor and Marie were taken to the hospitality room.

The ‘hospitality room’ didn’t quite measure up to that title. It was a grey-walled room with no windows and just a plain table and a few chairs for furniture. They were left there with the promise of refreshments.

“Great,” Marie observed. “Guests of the least hospitable people in the universe.”

“Oh, there are FAR less hospitable people than these,” The Doctor assured her.

“I feel so much better. Who do they think you are, by the way, with this VIP treatment?”

“Transport’s inspector of factories,” The Doctor answered, glancing at the psychic paper. “Come to think of it, this is rather a rubbish way to treat a company official. Where are the refreshments?”

In answer to that question, the door opened and a teenage girl wearing orange overalls inexpertly adapted to her petite size brought in a tray containing plastic cups of something similar to coffee and something a little like energy bars which, when Marie tentatively tried one, tasted like cheese and onion crisps.

“You… seem young to be working in a place like this,” she said conversationally to the girl.

“I’m Amber,” she answered. “Amber Anders. My father is the site manager. I had to come here after my mother died back on Earth. I don’t really work, as such. I just help out. Is it… is it true that you found a body?”

“Yes, a man called Monk… Paul Monk.”

“Oh.”

“You… don’t seem too upset,” The Doctor observed.

“I… don’t really like Mr Monk. He… tried… once… in the corridor….”

Marie was shocked, not only at the implications in the blank spaces of the sentence but the still rather matter of fact way the girl talked about something quite horrifying.

“I…” Amber began, then touched her ear suddenly. Marie noticed that she had a small in-ear device, something like very well equipped concert security or American special agents used. Had she received some sort of message through it? Was it an instruction not to talk to them about the murder?

Marie would have questioned Amber further about the murder and about life generally in an industrial plant on a hostile planet but the door opened again. The man in orange who entered had the name Anders on his top pocket, and Amber addressed him as ‘dad’, which summed everything up about the two of them.

Marie looked carefully and noticed that he was wearing a discreet ear device, too.

“Doctor… umm…. Doctor,” Anders said, reaching to shake The Doctor’s hand. “I’m sorry I wasn’t here to greet you immediately. I was not expecting your inspection.”

“Inspectors are just like the Spanish Inquisition,” The Doctor said with a broad and deliberately condescending smile. “Nobody expects the Inspectors.”

Anders didn’t get the joke. Either Monty Python didn’t survive into the age of space colonisation or he had no sense of humour. For the sake of humanity, Marie hoped it was the latter.

“What about the body?” Marie asked. “Have you….”

“Oh, yes,” Anders answered her too quickly and too airily. “Thank you for bringing the matter to our attention. An unfortunate accident….”

“Accident?” Marie queried. “His head was missing.”

Anders didn’t respond to that. Marie wasn’t sure if it was some kind of chauvinism that allowed him to ignore awkward questions from women or a deliberate deflection, but he really wouldn’t go any further about the strange death of Mr Monk.

Maybe Anders murdered him for his corridor antics with Amber?

Whatever the truth was, Anders had already ticked off the death of his colleague on his mental agenda. He went straight to offering to show The Doctor around the plant personally.

“Usually, I go where I choose,” The Doctor answered. “And talk to who I choose. Head office likes to know nobody has anything to hide.”

“This is a large plant and many of our operations are dangerous,” Anders pointed out, reasonably. “Untrained personnel may put themselves and others at risk.”

“I’m health and safety trained,” Amber piped up. “I could show them around.”

That was hardly allowing The Doctor to go where he chose, either, but it was a compromise acceptable to both sides. Amber smiled broadly as her father left her in charge of the inspector’s visit and invited The Doctor and Marie to follow her.

The basic tour was more or less self-explanatory. The plant was there to extract the yellow gas that made the planet so unsavoury. In its refined form it was a valuable fuel that was sold across the Earth Federation for considerable profit.

“So, this ISN’T a colony at all,” Marie surmised. “Just exploitation of the resources.”

Amber didn’t comment about the moral aspect of the operation, but she knew the facts and figures about how many cubit metres of gas were transported by how many huge space freighters.

She expounded upon that as she showed the two visitors around the different sections of the plant including the raw gas input and several stages of refinement through which impurities were removed from the gas.

“Where do the impurities go?” Marie asked. “I hope they’re not being pumped back out into the environment. It’s bad enough as it is.”

“And no hiding it underground, either,” The Doctor added. “I had all sorts of trouble with that kind of thing in Wales.”

Amber was peculiarly unhelpful about that. But she was only a teenager, and perhaps she wasn’t fully versed in the processes.

The Doctor and Marie both asked the managers of the refinement sections the same questions, but the answers were disturbingly vague.

Another part of the process that puzzled them both was the dispatch department. This was where the huge silos came in, storing the millions of cubic metres of gas in double-lined, pressurised tanks ready for transporting to the superfreighters.

But where were the superfreighters? The launch pads were empty and when The Doctor checked the schedule there didn’t seem to be anything arriving for some time.

“I don’t understand this,” he said. “You’re producing enough gas to lift this entire plant off the ground, but none of it has been shipped out for months. There ought to be two or three departures every day.”

Amber couldn’t answer that question. Neither could any of the people working in the dispatch department. Most of them couldn’t even recall accurately when a freighter last arrived.

“Well, if it isn’t being shipped out,” Marie said, looking up at the storage tank. “Then where IS it going? Are you SURE it isn’t being pumped right out again into the air?”

Amber frowned as if she was trying to think of an answer to the problem, then she squinted as if she’d forgotten what the question was and touched her ear again. She did that, Marie had noted, every time there was a question that wasn‘t covered by the standard information she had memorised.

Everyone else they might ask about the anomaly had gone back to their work and wasn’t listening at all. Amber smiled brightly and asked if they wanted to see the living quarters.

“Yes, good idea,” The Doctor said quickly. “Personnel. Never neglect personnel. An old friend of mine called Donna was always reminding me of that. Supertemp, phenomenal typist, great office skills. Knew the Dewey decimal system by heart.”

He was digressing deliberately. Marie had seen him do it before. It gave people an enormously false sense of security. It also tended to make them talk much more, in order to get him to stop digressing, and they often made huge mistakes when they did.

Amber didn’t make any mistakes, but there was something about the living quarters that both answered many questions and suggested a whole lot more.

After inspecting the rooms shared by up to four workers in two sets of bunks, and the kitchen where their meals were prepared, Amber showed the visitors a recreation room with games, video screens, a library, anything an off-duty worker might while away the hours with on a planet where outdoor pursuits weren’t an option.

Except none of them were using the room just now.

“Have you read this book, by the way?” Marie asked Amber, pulling a paperback from the library shelf. “Watership Down. It must be a real classic by now. It’s on the list of books I teach the top class. Its kind of hard going even for a book about bunnies, but around about the middle the heroes come to a warren where all the rabbits are fat and healthy, but there’s only about half of them, because a local farmer puts down food to lure them into a false sense of security before trapping them.”

Amber looked puzzled. The Doctor looked smug. He knew where Marie’s own divergence was going.

“The rabbits in the warren could never answer a straight question. They were always vague and difficult, because they were scared to admit the truth.”

“A bit like THIS warren,” The Doctor added. Amber looked at him with an expression something like a bewildered rabbit.

“I don’t understand,” she said.

“No, I don’t suppose you do. It’s not your fault. Your dad has a lot on his plate. More than he ought to, and he probably wouldn’t want to involve you. But there is something wrong here.”

“It’s like the half empty warren,” Marie added as The Doctor paused for breath. “This place is huge. Bigger than any factory I know. But there are nowhere near as many workers than I’d expect. Granted, you’ve got computerised robotics doing a lot of work, and it only takes one man to press a button. That cuts the workforce down, especially if there are no unions to complain about redundancies. But looking at how many bunks are empty in the rooms, I reckon you only have about a quarter of the people here you’re supposed to have. Not enough for more than one workshift. That’s why the rec room is empty right now.”

The Doctor nodded in satisfaction. Even Marie’s human pudding brain could work out the problem.

“So, Amber,” he began, then reached quickly and grasped her hand midway to her ear. Gently but firmly he removed the earwig and dropped it in his pocket. “So… how many people around here have had their heads bitten off like your Mr Monk?”

“And are they all listed as tragic accidents in the company records?” Marie added.

“They…” Amber began, then her eyes widened to full ‘rabbit caught in the headlamps’ as she looked past The Doctor’s shoulder. “Dad… NO!”

The Doctor grunted as he was felled by a blow to the head with a lump of metal. Marie backed away only to be grabbed by one of Mr Anders’ colleagues with a rag suffused with a noxious liquid. She heard Amber cry out again as she slipped into unconsciousness.

Marie recovered her senses slowly, aware first of all of the discomfort of lying on something metal that was imprinting a grid pattern on her shoulders. She struggled into a sitting position and looked around at the industrial scaffolding she was resting on. It was the man-made part of a huge cavern, the rock walls glistening with the usual yellow of this planet, which had a phosphorescent property that dimly and eerily lit the space.

On the cavern floor below were a number of plastic vats filled with what she immediately guessed was the stuff extracted from the refined gas. What was most horrific, though, was the movement of creatures across the vats, as if grazing on it.

“They are,” The Doctor said, his voice close to her. “It’s like royal jelly to the elite of them. Look over there, by the wall. The refined liquid gas is pumped down to feed the rest.”

She looked. The sight of so many of the creatures revolted her.

“They’re… like giant crabs,” she said. “Really giant….”

“Macra,” The Doctor confirmed in a tone that worried her. “Yes. I’ve seen them before. Don’t worry, we’re safe up here for now. They’re not big climbers.”

“They… Anders and his friend… dumped us down here… to be eaten by them… beheaded, like your man, Mr Monk?”

“Beheaded rather than eaten,” The Doctor confirmed. “Give me a minute or two for the mother of all headaches to clear and we’ll get out of here. I’m seeing double and triple depending which way I look. Getting us up this far was a struggle. I’m guessing it was complete coincidence that Anders whacked me on the very part of the skull that really gives my species trouble.”

“These… Macra… you know that’s the name of the Young Farmer’s Association in Ireland. That must be a coincidence, too.”

“Unless young farmers in Ireland eat the still quivering brains of their foes in order to absorb their knowledge, I should think so.”

“You said you’d seen them before….” Marie passed over that gruesome image.

“Twice… two different kind of Macra. The royal jelly eaters… they’re sentient. They have some measure of telepathy and powers of mesmerism. I met them once, keeping a whole community of humans in their thrall, processing the gas they live on.”

“That sounds familiar,” Marie pointed out. “And the second time….”

“A bunch of the non-sentient kind… those over there… were attacking motorists on a seriously polluted motorway. Long story. Funny thing is, I’ve never seen both kinds together. I assumed the dumb ones had devolved from the clever ones.”

“Which would you rather fight?” Marie asked, looking at the swarm of pincers and feelers reaching from under Kevlar thick carapace and wondering if crabs could actually climb. Were they as safe as The Doctor had assured her they were?

“Neither,” The Doctor answered. “Come on. There’s a door but we need to climb a bit further. Are you up for it?”

“Rather than stay down here with that lot… I’ll crawl on my hands and knees if necessary.”

She wasn’t quite that bad, but she was glad of a metal stair rail on the climb up two levels until they reached a strong bulkhead door with no obvious handle on this side.

“That’s… not a huge problem,” The Doctor assured her. “The sonic screwdriver DOES do metal.”

It took a few minutes, but the grinding of the lock soon accompanied the whine of the sonic. The door opened inwards. They climbed out into a corridor near the distribution silo.

“Excellent,” The Doctor said with a manic smile. He strode across the busy room to the computerised operating system. It took only a few keystrokes to switch off the conduit feeding liquid gas to the Macra down below. He had cut off their food supply.

“Hey, what are you doing?” asked the distribution foreman. The Doctor waved his psychic paper and waggled his sonic glasses.

“That conduit stays off until further notice,” he said. “And remove your earwigs. Pass that around the staff. Health and Safety directive. No more buzzy noises in your ears.”

The foreman nodded and pulled the device from his ear before going to find a ‘do not operate’ sign for the conduit.

“Now let’s find Anders and get the truth from him,” The Doctor said. Marie had, in one corner of her mid, hoped they would just go back to the TARDIS and go somewhere nicer, but she knew he would never do that, and mostly, she was glad. She wanted to confront the people who had tried to do away with them and find out why.

Anders and his colleague, with the name ‘Dudley’ on his overalls was still in the recreation room. Amber was with them. She had been crying. When she saw The Doctor and Marie, both with their heads on their shoulders, she looked much happier.

Her father and Mr Dudley were less pleased.

“Sit down and shut up,” The Doctor said to them in tones that brooked no refusal. “Amber, be a good girl and bring coffee for everyone. I’m just going to have a chat with your dad.”

He sat down between the two men. Marie took her place opposite him. Amber hurried to do as The Doctor asked.

“First of all, take out those earwigs,” he said. He held up the one he had taken from Amber. “I had a close look while I was waiting for Marie to come around. I’m not sure how they managed it, since they don’t have opposable thumbs and aren’t noted for their micro technology, but the Macra somehow persuaded you all to wear these.”

“They’re human technology,” Anders answered. “We use them for communication within the plant. There’s a lot of noise. Shouting isn’t advisable….”

“That explains that. The psychic Macra elite took over your technology. They’ve been feeding you a sort of soporific white noise that inhibits questioning or resistance and stops you from worrying about headless bodies popping up all over the place. They also instructed you to stop exporting the gas and instead provide it to them as an on-tap food source. I don’t think they’re exactly monitoring your movements, but they must be able to recognise mood changes. That’s how they influenced you to attack us.”

“I….” Anders began. It sounded like an attempt at an apology. The Doctor brushed it aside. He wasn’t interested in words when actions were more important.

“How can we fight them?” Dudley asked after laying his earwig on the table. “They’re stronger than we are.”

“No, they’re not,” Marie answered. “For one thing, they’re dependant on you to feed them. Stop doing that. What would happen if you pumped fresh air down into the cavern instead of the gas they like?”

“It would kill them,” The Doctor said. “It’s bordering on genocide and there are rules about that.”

“You mean you’d stop them doing it?” Marie asked.

“I said bordering,” The Doctor assured her. “The thing is, this planet isn’t the Macra’s natural home. If it was, they would be everywhere. They’re strictly confined to the lake and the cavern beneath this plant. I think they came here some time after you lot and latched onto your operation. It wouldn’t be genocide. It would be a sort of ethnic cleansing.”

“That doesn’t sound quite so moral, either,” Marie pointed out.

“No, it doesn’t,” The Doctor admitted. “Besides, I already instigated the other option. I’ve cut off the main food source from the liquid gas pipe. Keep it that way and stop dumping the waste into the cavern. That was a foolish idea, anyway. Bound to make trouble. Get the ships running again and start exporting at full capacity, reducing how much natural, unprocessed gas there is available. The Macra will know that their meal ticket has expired. They’ll leave the planet by the same means they got here, without any trouble and no more unnecessary deaths… for you or them.”

“We can do that,” Anders confirmed.

“You should have done it by yourselves,” Marie chided. “Fancy letting a bunch of scrappy crustaceans take you over like that. How long would this have gone on for if we hadn’t turned up?”

Anders had no answer to that, but his head was clearing without the Macra influencing his thinking. He promised to put the changes into operation right away.

“I’ll be checking up,” The Doctor warned him. “That’s what company inspections are for, after all. Meanwhile, Marie and I will be going, now. It was lovely to meet you all, but I would really like a decent cup of coffee.” He looked into the turgid brown stuff in the cup in front of him. “You might mention that to head office. Get them to send you some decent supplies, now you’re not being hypnotised into not complaining. Come on, Marie.”

And that was that. Just for once there was no battle against fearful odds, just some really bad factory organisation. He walked back to the TARDIS feeling quite cheerful about it all.

“Doctor… look,” Marie exclaimed as they reached the place where they had found the body of Mr. Paul Monk. Now, a freshly dead Macra lay on its back by the side of the lake, its massive pincers stiffly raised over its eviscerated underbelly.

The Doctor looked closely then withdrew quickly. He looked into the polluted water and saw half a dozen smaller creatures swimming away.

“Well… that’s interesting,” he said. Marie looked at him in surprise. Interesting wasn’t her word for it. “The dead one is an elite, one of the sentient. It was killed by some of the animal ones.”

“How come?”

“I cut off the food supply. That was the only thing keeping them tame. They turned on their masters. I wasn’t expecting that, but it might just persuade the Macra to get out of here even faster. Good news for the humans, at least. Come on. I really do fancy a good cup of coffee. Something to eat would be nice, too. I know plenty of good restaurants.”

“Ok, but… you know….” Marie looked at the dead Macra again and shuddered. “Nowhere that does shellfish.”

|

|

|