Marie had regretted this idea at least two hundred times in the past hour. It was fraught with disaster. It was worse than a trip to the zoo, and look how THAT had turned out!

“Nearly every child in the junior classes has been off for the past month with measles,” she had told The Doctor. “Six of mine had it the year before, so they haven’t been sick. That’s the good news, of course. But it means they’re stuck at school while everyone else won’t be back until January. And its a school with no decorations, no Christmas party, no Nativity play, no Pantomime, none of the things that make the run up to end of term fun for them.”

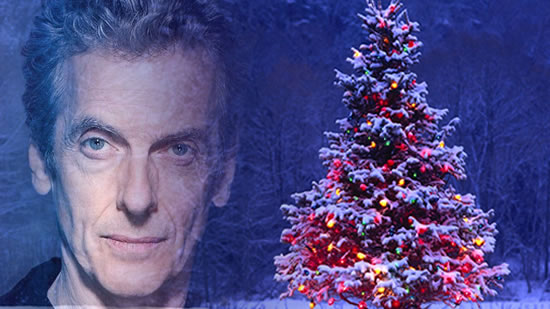

“Grim, indeed,” The Doctor had noted lugubriously. He was the only person Marie knew who could do ‘lugubrious’. Before she met him it was a word that popped up in Victorian literature without any clear explanation. But he nailed it.

“So, I was wondering, is there somewhere fun you could take them in the TARDIS? Something to blow their minds and give them back their Christmas Cheer?”

“Where do you suggest?” The Doctor had asked, passing over the idea of six dispirited ten year olds in his TARDIS. “Short hop to Lapland to see the reindeers, that sort of thing?”

“Something like that,” Marie had answered. “Didn’t you tell me once about an actual planet called Christmas?”

“Yes, but that’s just the name of it, like Easter Island or Piccadilly Circus. There are no chocolate eggs or clowns at either of those places. Believe me, I’ve looked.”

“But surely there is something?”

“Well,” The Doctor had finally conceded. “There is Christmas Station.”

All things considered, The Doctor had been gracious about the actual trip. Niall Driscoll’s bladder had resulted in the TARDIS reconfiguring itself to include a toilet directly next door to the console room. Colm Finn had been travel sick, Bridget Drennan’s nose had bled so much she looked like she should have had a transfusion. Gerard O’Connor and Liam Murphy had both had panic attacks in which they claimed the walls of the console room were closing in on them.

Áine Burke had sat in the corner biting her fingernails the way she did every day in class. Marie had spent all of the autumn term trying to work her out, fretting over the thought of a child like that being thrown upon the shark infested waters of secondary school in another year’s time.

The Doctor, not ordinarily known for his tolerance of the Human race’s domestic mess, had put up with it all for an hour before announcing that they were ‘there’.

“Where?” asked Colm Finn, discarding his sick bag in a receptacle under the console that the TARDIS had acquired out of necessity.

“Christmas Station,” The Doctor responded, flicking a switch that turned on the big viewscreen – the one that outdid the flattest, biggest, HD ready television available. Filling the view was a space station that looked exactly like a huge Christmas Tree. Lights from two hundred decks sparkled like baubles and a beacon at the top shone like a multi-coloured glass star against the panorama of real ones.

The children were impressed. Even Áine looked at it and managed to raise her eyebrows.

“It’s looked like a pudding for the past few years,” The Doctor added. “Boring, really. I mean, who would care about a big round thing at the end of the solar system?”

“Our actual solar system?” Liam asked.

“Your actual solar system,” The Doctor assured him. “That’s Pluto it’s in orbit around. In the Fifty-fourth century it’s been reinstated as a planet.”

“Ok,” the boy conceded, not quite sure, yet, if this was all some kind of virtual reality show in the school hall.

“Ok?” The Doctor replied as if that was an actual challenge. “I’ll show you ‘ok’. Stand by to materialise on the arrivals deck.”

The short hop from parking orbit to ‘there’ caused Colm to reach for a fresh sick bag, though it wasn’t needed. When they retrieved Niall from the toilet they were ready to disembark.

Of course, Marie had said ‘fun’, not ‘tasteful’. She appreciated the difference as soon as they stepped from the hangar bay where The Doctor had left the TARDIS among an assortment of personal space shuttles and moon hoppers and into the ‘foyer’ of Christmas Station. Amidst a phalanx of brightly decorated Christmas trees they were greeted by young men in green elf suits and young women in red satin ‘Mrs Santa’ dresses of the sort that made Santa regret being quite so overweight. They handed out candy canes to children and adults alike and welcomed them to Christmas Station.

There was a collective groan from Marie and her party about the music playing. The party were of one mind about Bing Crosby singing Christmas in Killarney.

“I’ll give him ‘Holly Green’ up his nose,” Marie threatened, but not completely seriously. Fake nostalgia for a kind of Christmas that never really existed in any past era was a part of the experience.

Besides, everyone, even Colm with his issues about travel, got excited when they saw the steam train taking on passengers.

“Wow, it’s the Hogwarts Express!” Gerard O’Connor exclaimed.

“No, it’s the Christmas Express,” Bridget replied, pointing to the embossed name along the side of the water tank. “Christmas colours, red and green.”

It wasn’t quite a full size locomotive, perhaps about two-thirds of the expected dimensions. The gauge of the track was probably smaller than standard, too, but it was still a steam engine of the sort that got boys excited. The Doctor looked impressed, too.

“They used to have a sleigh with unconvincing animatronic reindeer,” he said. “This is far superior.”

“Can we go on it?” The requests were multifold. Every child, even Áine, who was rarely interested in anything, displayed enthusiasm for a train ride in space.

“See all of the highlights of Christmas Station in a ninety minute tour, then decide which bits you want to spend quality time in,” explained one of the Mrs Santas. “Perfect for the first time visitor or the indecisive.”

“Please can we go?” The gestalt cry was pitched at a perfect level of plaintiveness to persuade any adult. Around them parents were being persuaded in their droves.

The Doctor glanced at the carriages critically. They were red and green liveried, too, with festive garlands hanging inside. They were the very old fashioned sort with two wide leather seats facing each other, lots of widows so everyone could see out on both sides, but no connecting corridors and no toilet facilities.

“Niall, hold it in,” The Doctor warned as he held open a carriage door and ushered his charges inside. Marie was last in before him and he closed the door before dropping the window to get the full experience of steam travel – mostly a faceful of smuts.

The youngsters were excited as the train moved off. They hugged the windows and watched as the train passed into a tunnel, but not a dark, featureless one as they might have expected. This was Christmas Station and the tunnels were lit with twinkling multi-coloured lights. If Christmas trees had an inner soul, this was it.

They emerged after a few minutes in a winter wonderland. The train chuffed past a landscape of picturesque cottages set in a snow-covered landscape as seen in the most hopeful Christmas cards. A couple tucked up with blankets drove an actual ‘one horse open sleigh’ along the lane towards one of those houses. A four-in-hand full of party goers muffled up in warm clothing went the other way. On the far hills there was tobogganing and skiing and a perfectly frozen lake provided skating for all levels of competency.

“We ARE still on the space station? Liam asked. “Only it’s snowing and the sky looks….”

“Is it real?” Gerard asked.

“In so far as it’s an artificially stimulated microclimate and the hills are not as far away or as high as they look, its real,” The Doctor explained. “Trust ten year olds to ask the awkward questions. You’re supposed to suspend disbelief and enjoy it.”

“We’re enjoying it,” Liam and Gerard both assured him. “It’s just mad, that’s all.”

“I like it,” Bridget admitted. “We don’t get snow like that in Tallaght.”

“If we did, it wouldn’t be fun,” Colm pointed out. “It’d just make the buses late.”

“He’s right,” Marie agreed as they passed a field full of people having snowball fights and a couple building a snowman in true ‘walking in a winter wonderland’ style. “It really only looks fun in nineteen eighties pop videos and Christmas card scenes. Real snow is hard work.”

“Well, that’s you lot all down for the snowman building competition, later,” The Doctor said. “Including you, Miss Reynolds. I thought it was just the kids who had lost their Christmas spirit.”

“It’s been hard on the teachers, too,” she pointed out. “But I’m here, aren’t I? Ready to have my spirit renewed.”

“Hey, where is the train going, now?” asked Niall. “It looks like we’re going into the hill, under the ski lift.”

“Off to another Christmas zone,” The Doctor explained. “There ARE two hundred decks on the station, and you want to see plenty.”

The train entered a tunnel straight through the snow-covered hill. Again, there were multi-coloured lights but nothing to compare with the sight when they emerged.

“Oh, it’s the Fête des Lumières!” Marie exclaimed as she looked up at a glass dome with a star field of deep space beyond and a glorious display of dancing multi-hued aurora on the inside. All around this deck tableaus of colour and movement were created by projecting lights onto objects. The train slowed as it passed between an avenue of trees made to look like fountains and fountains that looked like trees. Beyond that they entered an underwater world projected onto curving glass walls.

“What’s a fate dur… whatever?” Liam asked.

“Fête des Lumières,” Marie repeated. “It means ‘Festival of Light.’ I suppose it could be anywhere, but the main one happens every December in Lyon, in France. The whole city centre is lit up, churches and cathedrals and public buildings all covered in lights. I’ve never been there, but I always look at the virtual tour online. It is fantastic. More fantastic than this version of it, really, because it’s done by ordinary human effort in our own time and no space age technology.”

The Christmas Station fête took all of the best elements of Lyon’s tradition and put them under an exo-glass dome at the top of the station. Visitors walked around in rather more comfort than they did in the open air in France, in December.

All the same, Marie’s students were more impressed by the idea that something as spectacular as they were looking at here on the future time space station happened in their own real time. Of course, the chances of any of them seeing it were slim. It was at least nine hundred miles away from their home and hotels in the city were the most expensive on the weekend of the Fête. It wasn’t even within the scope of possibility for them. That fact had something of a deflating effect on the youngsters. They looked at the reproduction of the Fête with rather jaded eyes and weren’t especially sorry when the train passed into another tunnel, leaving it behind.

“Christmas Station doesn’t usually have to work so hard,” The Doctor admitted. “Perhaps the next exciting deck of Christmas joy will inspire you lot.”

What they emerged into was a giant feast of Christmas fantasy – Santa’s grotto complete with magical toy factory. Elves with smiling eyes and rosy red cheeks happily hammering at wooden toys while a jolly, fat santa in red walked among them checking on productivity and huge ‘naughty and nice’ lists hanging from the wall either side of the train tracks. It was pretty and imaginative, but perhaps not quite enough for ten year olds with all their doubts about the reality of Father Christmas.

“Who do they make all the wooden toys for?” Niall asked. “Nobody wants a wooden aeroplane for Christmas.”

“The wooden toys are just figurative,” The Doctor explained. “In the sleigh they turn into Nintendo consoles and whatever was on your list.”

“Do you expect us to believe that?” The youngsters all looked at The Doctor with acute scepticism. He smiled back enigmatically and refused to be drawn any further on the matter.

As if that wasn’t bad enough, the students of the senior class of East Tallaght Community School were, to a child, unexcited to see their names on the ‘nice’ list.

“We didn’t tell anyone here our names,” young Gerard explained. “So that bit is just…..”

“Creepy,” Niall suggested.

“Plus, I know I’ve not been ‘nice’,” Liam added. “I’ve… done stuff I shouldn’t have.”

He wasn’t prepared to expand upon his confession, even with The Doctor glancing at him with the most fearsome eyebrows.

Meanwhile two more of the boys admitted they probably shouldn’t be on the ‘nice list’ either.

“I haven’t done anything wrong,” Brigid said after a moment. “But my da hasn’t had much work this year and mam’s having another baby, so being on the ‘nice list’ doesn’t mean anything. Christmas will be what we can afford.”

It hadn’t been as financially rough for the others, but they all admitted to understanding the harsh economics of Christmas that Santa couldn’t just magic away.

The Doctor couldn’t magic it away, either. As they passed into the tunnel to the next attraction he realised that the level of Christmas spirit in the carriage had actually DROPPED several degrees since the novelty of a steam train wore off.

“You lot are the biggest challenge this place has had for a long time,” he admitted.

Marie agreed.

“Any idea what else is on the tour?” she asked.

“Well, there’s usually a cultural element – three dimensional representations of famous nativity paintings, the Old Masters, that kind of thing....”

“Interesting, but I’m not sure if it would take Niall’s mind off his bladder,” Marie conceded. When The Doctor mentioned Victorian street scenes with carol singing that. didn’t sound hopeful, either.

“Have I got it wrong?” he asked. “I thought this place would be sure to cheer them up. It has everything you could want from Christmas under one roof – well, one exo-glass skin, anyway.”

“But most of what people want from Christmas is fantasy,” Marie pointed out. “They’re from Tallaght. They’re too aware of real life to succumb to fantasy easily. Maybe Christmas Station should admit defeat, this time.”

“You could be right,” The Doctor conceded. “We need to think this through a bit. There’s a request stop coming up. The food court. Maybe turkey and chestnut stuffing subs and minced pies with cream will cheer everyone up.”

“Plus, Niall will be able to find a bathroom,” Marie added.

And perhaps that MIGHT have been a good idea, but it was within the next tunnel that things started to go wrong. The Doctor had guessed, though he hadn’t shared his guess with anyone else, that the tunnels were a cover for space age technology. Each of the decks they had seen were far apart. The Fête des Lumières was on the very top deck with the exo-glass domed roof. Santa’s grotto was three floors beneath the shopping arcade and Christmas department store. The Winter Wonderland was on deck four just above the hydrogen cooling plants that generated the snow. The tunnels were, in fact, instant transmat chambers, shifting them between the decks. Up until now that had worked smoothly enough. Nobody had noticed anything other than forward motion of the train. Even Marie hadn’t questioned it.

But this time they were all too aware that they were not travelling under steam power. Colm retching into a paper bag was the last thing The Doctor heard as the nauseating sensation of an unguarded transmat overcame even him. The last thing he felt was a small hand gripping his. Exactly who’s hand he thought it was owed much to a long life full of short acquaintances and often painful parting.

When he woke again, he recognised that the slightly sticky hand belonged to Áine. The two of them were alone in a dark alleyway with soot-tainted snow on the ground.

“Sugar,” he managed to say. “We need sugar. The transmat has reduced our blood glucose to dangerously low levels. Diabetic coma is imminent.”

Áine reached into her pocket for the candy cane given to her at the start of the Christmas Station experience and which accounted for the stickiness of her hand. She broke it in half and shared it with The Doctor.

“I’m cold,” she said. “It’s really cold here. And I don’t have my coat.”

She was wearing one before. All of the children had coats and hats and gloves of some sort – most of the gloves being the sort with strings through the coat sleeves to prevent them going missing. Now she was clothed in a very thin and unwintry cotton dress and a very dilapidated pair of shoes with a wafer thin bit of sole left on them.

His clothes were the same as before. Nobody messed with his clothing even when he was unconscious without a reckoning. The Doctor pulled off his coat and the hooded sweatshirt from underneath. He put the hoodie on the girl making a baggy sort of woollen dress and put the coat back on himself.

“Now you’re a bit warmer and I’m a bit colder,” The Doctor told her. “I think we’re going to have to put up with that for a bit. Let’s see where we are.”

Where they appeared to be when they emerged from the alleyway was Victorian London. In truth it could have been Victorian Glasgow or Manchester, or even Dublin, but narrative causality made it London. It was dark and it had been snowing for a long time. There was nothing charming about the way the falling flakes could be seen in the light of the gas lamps. It was too cold for any sentiment other than irritation.

There was nothing charming about being improperly dressed in winter, either. What made it worse was that they were surrounded by people who did have warm coats and scarves and gloves were all around. Even more painful was the fact that those people had money to buy packets of hot chestnuts or roast potatoes from vendors with hot braziers. Being hungry as well as cold, and on top of being lost and confused, was no fun at all.

The Doctor dug deep into the pockets of his coat, knowing instinctively that they were empty of useful things like his Sonic Screwdriver or any viable currency.

He found two pennies with Queen Victoria’s glum face on them.

“The chestnuts are two pence,” Áine pointed out hopefully. The Doctor gave her the pennies. She ran off, returning presently with her cold hands wrapped around a cone shaped paper bag. She offered the open end to The Doctor. He took one of the chestnuts and peeled it. The morsel of hot food was welcome, but he let the child have the rest of them. She had a hungry, pinched look even before they were pitched into this odd simulacrum of destitution.

And simulacrum was the appropriate if rarely used word for it. The whole thing was fake. There was something just a bit wrong about everything here, from the yellow of the glow from the gas lamps to the jangle of the reins on the hansom cab horses. It wasn’t just fake. The Dickensian Christmas themed deck of Christmas Station was fake, anyway. But this was a fake of the fake.

“Miss Reynolds!” Áine cried out, suddenly.

“Where?”

“There.” Áine pointed to a woman in a very thin shawl who was selling matchbooks on the street corner.

“How corny,” The Doctor remarked. “The match girl!”

He walked straight up to her. She held up a matchbook hopefully.

“A farthing, guv,” she said in a fake cockney accent that was murder to the ears.

“Marie, wake up,” The Doctor told her. He touched her cold face gently and her eyes widened in surprise. She dropped the tray of matchbooks onto the snow-covered pavement.

“Doctor… what’s going on?”

“I’m not sure,” he answered as he pulled off his coat and wrapped it around her. “Now we’re all equally cold,” he added. “And equally bewildered.”

“Áine, are you ok?” she asked the girl. In fact, Áine looked more animated and engaged right now than she had been all term at school. She offered Marie the last, slightly cooler chestnut. She accepted it gratefully.

“We need to find the others,” Áine stated as a fact, just in case the grown-ups had forgotten.

“Yes, we do,” The Doctor agreed. “Marie, do you have any clue about that?”

“I can’t remember anything,” she answered. “Except… wait a minute…. There was a man….”

“A man?”

“He was….”

Marie shook her head. Everything felt strange and unreal. She turned around, though, and looked at a dark, ominous building that loomed over the street, blocking out a portion of the sky and somehow making everything in its shadow a little bit colder.

“What is it?” Áine asked.

“A workhouse,” Marie answered. “A worse fate than prison for poor people in the past. Don’t talk about it too much. You don’t want to give our government any ideas about dealing with poverty.”

“We’re missing five kids. Workhouses have kids in them,” The Doctor concluded. “Seems like a good place to look.”

He marched right up to the forbidding door of the terrible building and grasped a knocker shaped like the tormented face of Ebenezer Scrooge’s dead partner. He hammered it forcefully into the wood.

The door creaked open after a half a minute to reveal a skinny teenage boy with close cropped hair and ragged, grey clothes.

“I’m here for the latest arrivals,” The Doctor said, stepping across the threshold without waiting for an invitation. Marie and Áine followed. The boy closed the door behind them, cutting off the falling snow.

It felt colder inside.

They followed the boy through dimly lit ante rooms to what could, with a little charity, be called a dining room. Something like fifty or more children were sitting on benches at rough wooden tables eating something thin and grey served in portions too small to possibly fill them. Asking for more was probably not an option.

“There they are,” Marie said, pointing to a group huddled together at the end of the table. She walked right up to them and called each of them by name. They quickly came out of the trance that made them think they belonged in that grim place and looked at their dinner in disgust. It was a long way from the turkey subs that had been promised.

“Everyone here?” The Doctor asked. Marie did a head count. “All right, let’s get out of here.”

They would have done so except that Niall was desperate for the toilet again and Colm was vomiting up the gruel he had been eating.

Plus, the way out was barred by a tall, thin version of the character played by Harry Secombe in the film musical of Oliver.

“We’re leaving,” The Doctor insisted.

“I am the Warden of Christmas Station,” the figure replied. “These children are mine. All ungrateful wretches who refuse to find the Spirit of Christmas in what we have to offer are mine. They and their parents… the greedy and the selfish who think only of the value of their ‘presents’, clamouring in the toy shop for the latest noise making box of tricks, sulking when they don’t get what they want, forgetting that LOVE was the greatest gift given to all of Creation by the First Christmas.”

“We haven’t been anywhere near the toy shop,” Marie pointed out. “We haven’t had time to do anything except ride a train around a couple of floors.”

“All of which you have dismissed,” the Warden responded. “These children didn’t even appreciate being on the ‘nice’ list. They have so little spirit of Christmas they have even stopped believing in Santa Claus... at TEN years old.”

“I don’t think there’s a minimum age,” Marie pointed out.

“And YOU are just as guilty,” the Warden rounded on her. “You dismissed the magic of the Winter Wonderland. You thought our fête des Lumières was not as good as the ‘real one’.”

“It isn’t,” Marie answered, standing her ground.

“The Lumières on Christmas Station are bigger and better than anywhere in the human space colonies.”

“Only Americans think ‘bigger’ is ‘better’,” Marie retorted. “Your Lumières may be expensive and flashy, but they’re soulless. The Fête des Lumières in Lyon isn’t just about cramming the streets with tourists and selling them fast food. It is in memory of a time in the seventeenth century when the people of Lyon promised to honour the Mother of Jesus if they were spared the plague. Whether it was a miracle or fresh air and clean water, I don’t know, but ever since they have kept their promise with the lights and the procession and a Mass in the Basilica on the hill at the top of the city. The lights have got bigger and fancier because of technology, but the meaning of it all still remains. The centre of it all is still the Mother of Jesus, and if you need proof of that, a year or two back the people of France were feeling too sad for huge celebrations so they cancelled all the lights and fancy stuff and just had a candlelit Vigil at the Basilica. So, yes, their fêtes des Lumières will always be better than yours.”

The silence that followed was punctuated by a ripple of applause led by The Doctor and joined in by the children.

“I think Marie has made her case,” The Doctor said.

“She may have. These ungrateful brats have not,” the Warden answered. “They were still unmoved by any aspect of Christmas offered to them.”

“Well, of course they were,” The Doctor answered. “After all, everything at Christmas Station is as fake as the window dressing in Harrods. It’s all just for show, and to direct parents to the toy shop floor. These kids enjoyed your show, but they know it for what it is. Just a big advertising ploy.”

“Rubbish, they are ungrateful,” the Warden insisted. “They’re like all the others – their heads full of greedy Christmas wishes for piles of toys.”

“They’re not,” The Doctor insisted even more fervently. “They most certainly are not.” He looked around at the children, who looked back at him as if he was bargaining with the devil for their very souls.

“Áine,” he said, drawn to the biggest and most pleading eyes of them all. “Tell this man YOUR Christmas wish, the one top of your list.”

Áine said something very quietly, with her head down, the way she had replied to every question put to her in school all year.

“Louder, girl,” the Warden demanded. “What is it? Some doll with distastefully realistic bodily functions?”

“I wish that da would just go away somewhere so that me and mam can have a Christmas Day without him getting angry about some little thing and hitting us and throwing the dinner on the floor and breaking my toys,” Áine replied. “Like last year and the year before and….”

“Oh!” Marie hid her face in her hands. This was something she ought to have recognised as her teacher. There was training in spotting the signs. But between marking and assessments and sick days, Niall’s bladder, chewing gum under the desks and casual bullying, the quiet girl who said nothing had been forgotten.

“And if you ask any of the others,” The Doctor continued. “Naming no names, one of them is hoping their dad will be let out of prison in time for Christmas. Another is hoping for the all clear on his mum’s cancer. Most of them just hope that they can have Christmas without their parents fretting about how to pay for it. They’re ten years old and they already KNOW there’s no Santa Claus and no Magic about one arbitrary day of the year appropriated by Christianity from a pagan Solstice rite. They KNOW what the spirit of Christmas is about. They just don’t think it applies to them. Come on, kids, we’re leaving.”

He looked back at the other children at the long, dismal tables.

“There was nothing about this in the fine print on anyone’s ticket,” he added. “Everybody finds their spirit of Christmas their own way. If that means a mountain of expensive presents that’s their way. If its volunteering at the homeless shelter making sure others get fed on one day a year that’s another. If its….” He stopped and grinned like an alligator. “Never mind, all that. I’m not the narrator of a feel-good film. You can work out the moral of the story for yourself. Meanwhile, you let those children and their parents out of your little Scrooge pageant and stop judging them and Christmas by the one warped measuring stick. And do it before I reach the admin offices and lodge a very serious complaint about the way Christmas Station is being run lately.”

This time he was done. He brought his charges out of the forbidding building. He wasn’t entirely surprised to find that the fake Victorian London was starting to dissolve around them. Adults dressed in ragged and ill-matched clothes were heading towards the workhouse in search of their children and explanations about their unscheduled visit to this floor of Christmas Station.

“They must be the ungrateful ones who only care about presents,” Bridget noted. “Do you think they’ll learn the lesson?”

“No,” The Doctor told her. “That only happens in Disney films. Besides, the management of Christmas Station will modify their memories to avoid a lawsuit and offer them huge discounts on the piles of presents.”

Nobody thought that was completely fair, but that was just one more unfair thing about the situation.

The Doctor spotted a partially disguised entrance to a turbo lift and brought everyone to the parking deck where they had left the TARDIS. He didn’t need to take a vote to know that they had all had enough of Christmas Station.

He had a good idea about where they could get a real sense of Christmas spirit, too. The clues had been laid down thick enough. A mere half an hour later the TARDIS had travelled back to the early twenty-first century and parked in the Place des Terreaux in Lyon, France. The anachronistic and thoroughly noticeable blue police box was dwarfed by the projections of great works of art on the façade of the Museum of Fine Arts and of operatic tableaux on the front of the Opera House.

It was bitterly cold in December in the northern hemisphere, but everyone was snug in coats, hats, scarves and gloves. Hot chocolate from one vendor and warm croissants from another satisfied hunger pangs as they enjoyed to the full the REAL Fête des Lumières so eloquently extolled by Marie.

“You know,” she admitted to The Doctor. “Maybe SOME of it IS about commercialism. Try getting a hotel room this weekend at any price. But it still FEELS real.”

“That might be mild hypothermia,” The Doctor suggested, but he was just teasing her. By a roundabout way filled with mishaps she and the children had found their Christmas spirit and he could call that a success.

There was just one more thing he needed to do. He waited until later in the week, when Marie was at home, doing what school teachers did when they weren’t teaching. He parked the TARDIS quietly behind an Eirecom phone box of rather different dimensions and waited.

“Donal Burke,” he said, stepping in front of a man who walked home from the pub with an unsteady gait. “Appropriate surname, for a complete and utter berk.”

“Who the…. hell are you?” Donal Burke replied, punctuating the short question with profanities that The Doctor had learnt to edit out before the words reached his brain.

“I’m doing the talking, sunshine,” The Doctor answered, pressing a long finger into the centre of Donal’s skull. “You have a wife and a daughter you ought to love and cherish. You’ve got a job and a home and a lot less to worry about than a lot of people in your neighbourhood. You and your family shouldn’t be a concern to me. So this is what I’m going to do.”

“Wha….” Donal began.

“Still talking, which means you sh up. The feeling of disappointment and emotional turmoil you’re feeling is what Áine and her mum both feel when you go off on one of your moods for no reason. From now on you’re going to feel that instead of them until you stop getting in those moods. Meanwhile you and your family ARE going to have a good Christmas even if it kills you. Have you got that? Nod if you have.”

Donal nodded. The Doctor removed his finger.

“Right, away you go. And take this.”

“What is it?” Donal asked, looking at the gaily wrapped parcel.

“It’s a doll with distastefully realistic bodily functions, because despite the evidence of her home life, young Áine’s biggest ambition is to get married and have wee humans of her own and that sort of thing is practice, apparently. Can’t see it myself, but we didn’t have Christmas on my planet and even if we did I don’t think anyone would have given me a doll. Anyway, Happy Christmas, Merry New Year and all that.”

By the time Donal Burke had worked out the bit about the planet The Doctor was gone. So was the TARDIS. He shrugged and walked on home, a little more sober than before and with a strange feeling that things were going to have to change or it would be the worse for him.

|

|

|