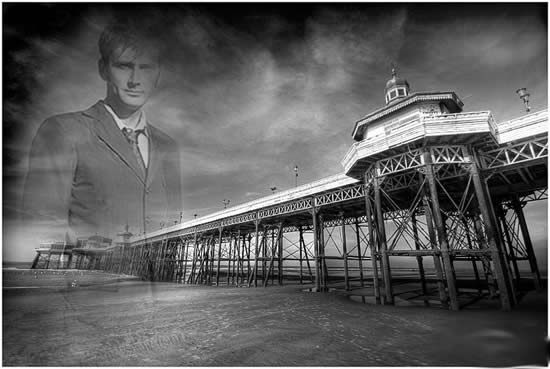

Donna and Ben huddled together in the shelter and looked out across the grey seafront. Neither of them were especially happy. They certainly weren’t enjoying their ‘holiday’. They couldn’t understand why The Doctor had brought them to Blackpool, in March. It wasn’t even open. And it was raining, hard. It was cold. They were, just to make the point fully, fed up.

“Where is he, anyway?” Donna asked. “He just wanders off and tells us to enjoy the view. Like… what view?”

“He’s coming, now,” Ben answered, looking around. The Doctor, in his tan overcoat and wearing his nerd glasses, was striding along the promenade as if he wasn't even aware of the rain. He was holding a plastic carrier bag with a blue drawing of a fish on it. He sat beside his two slightly damp friends and handed out warm wrapped packages.

“Fish and chips at the seaside,” The Doctor said, cheerfully. “Just the thing.”

Ben ate enthusiastically. He had been hungry often enough in his life not to refuse food when it was offered. Donna ate most of the fish and some of the chips because they warmed her up a bit. The Doctor seemed to be enjoying his.

“So, why are we here?” she asked. “Obviously not to go sunbathing.”

“There’s something happening around here,” he replied. “Something that caught my attention. I’m not entirely sure what or why, yet. But if we poke around a bit…”

“Ok,” Donna agreed. “Can we do the poking somewhere out of the rain? This is totally grotty.”

“I thought you’d enjoy a traditional English seaside holiday,” The Doctor said with perfect sincerity.

“Bring us back in the summer, and I might,” Donna replied.

“It is cold, guv’nor,” Ben pointed out. “Though I’ve been colder. This is a good coat. Keeps me dry. Days like this, in London, I’d have to hole up somewhere and keep warm. If I had no food I’d have to go hungry rather than get soaked and risk catching my death.”

“We’re going somewhere warm,” The Doctor assured him. He produced tickets from his pocket. Ben took them and studied them carefully. Now he could read, he never missed an opportunity to prove it.

“Professor Soon’s House of Nightmares Experience,” he read. “North Pier. Half Price Preview Ticket. Admit One.”

“Professor who’s what?” Donna sounded sceptical. “Doesn’t sound like my sort of thing, to be honest.”

“Professor of nothing,” Ben said with a voice of experience. “Mostly those things are all front. I’ve seen them at the music hall, and fairs. Fancy names, painted up all colourful, and its all smoke and bits of tinsel on the costume and lots of hand waving.”

“That’s my experience of such things, too, Ben,” The Doctor answered him. “Although I’ve known a few genuine professors in my time, too. I’m rather expecting this to be a more sophisticated version of the sort you’re thinking of - smoke and mirrors and flashing lights. In fact, I very much hope that is the case. Because Professor Soon is selling tickets to the public, drawing in innocent people. And if anything more than a clever bit of surreal seaside gimmickry is going on I will come down hard on him.”

“That I’d pay to see,” Donna said. “Come on then, let’s check out this Professor’s House of Nightmares.”

They made their way onto the pier. It was cold and windy and not much fun trudging out on the wooden walkway to where the new attraction stood. It looked just like any seaside attraction. It was built of flat boards painted in bright, garish colours. There were images of ghosts and ghouls and assorted ‘nightmarish’ things that didn’t look especially scary.

“It’s a sort of ghost train?” Donna queried. “That’s nothing special. Are you sure this is worth our effort, Doctor?”

The Doctor said nothing, but he showed her something concealed in his hand. It was his psychic paper. There was something written on it.

“Danger! Beware!”

“It’s in my own handwriting,” The Doctor said. “My latent precognition is warning me.”

“Then maybe we should take your latent precognition’s advice,” Donna suggested.

“I agree,” Ben added. “Listen to yourself, Guv’nor.”

The Doctor smiled. Then his smile widened to a grin and he presented his ticket at the kiosk. Ben and Donna sighed in unison and went to join him. If he insisted this was trouble, then they weren’t going to let him get into it on his own.

As she shuffled along the rope queue and waited for their turn to go into the ‘Experience’ Donna reminded herself that The Doctor asked her to come along with him as a secretary. Of course, she had known from the start he didn’t want a secretary. She had done very little that could be classed as secretarial work in the past year.

And she was definitely not going to let him get into something dangerous without her watching his back. That was her real job. Looking after The Doctor. He might not think so. But she was. And so was Ben.

The door opened and they stepped in. As they did so, something occurred to Donna.

“We didn’t see anyone come out. Usually there’s an exit door that people come out of before new people go in. Where did they go?”

She turned. She wanted to go back out. But the door was closing. The grey light of the miserable day seemed suddenly very welcoming as it was cut off from her view. She reached out and grasped Ben’s hand and put out her arm towards The Doctor. He took her hand, too, smiling reassuringly.

Then the lights went out. Donna didn’t scream, though she heard a couple of women shriek theatrically and a couple of young men laugh derisively as if to prove that being in the pitch dark didn’t bother them.

Then other lights came on. Donna felt both men still holding her hands. If she really concentrated they were there. She could feel the pressure of their flesh against hers. But it was becoming harder to concentrate.

There were lights flashing on and off in a disturbing way, and distorted images around her on the walls and ceiling. The images span around and it was like being in a tunnel of light and shadow. It reminded her of something. She tried to remember what. She found it difficult to remember anything and fought a sort of fog in her head.

She remembered. It was the old version of Willie Wonka’s Chocolate Factory, the bit in the film where the Wonkatania went into the tunnel. The images that were whirling around her faster and faster reminded her of that scene. The same feeling of fear and uncertainty gripped her. She tried to hold onto the memory of that film, a colourful fantasy with music and dancing and just that one rather frightening scene. She held onto the music and colour and joy and for a little while it was her shield. It kept the whirling images at bay.

For a while. Then she succumbed as she knew everyone else had already succumbed. She saw that the images around her weren’t vague, general ones. They were specific images. They were images from her own nightmares.

She looked around. She wasn’t surrounded by whirling images in the dark, now. She was in the bright sunshine. She was in the garden of her own house.

Not her own house. Not the one she lived in now. The house she grew up in. She saw the lawn, the garden shed, the swing that she used to play on. She saw the back fence. She saw the fences either side, the washing line of the house next door. Her mother never put out washing. She had a tumble dryer. She considered herself superior to the woman next door because she had a tumble dryer.

Donna looked down and saw that she was wearing patent leather shoes and white socks. She was a child again. She was about ten.

It really was a nightmare, Most people probably wouldn’t think so. The sun was shining. She was home. She was safe. It would be a sweet nostalgic memory for most people.

She looked at the back door. The last thing she wanted to do was open that door. But something compelled her to walk closer. She couldn’t stop herself. That was part of the nightmare. Her inability to run away. There was nowhere to run to.

She put her hand out and pushed open the door. She stepped into the kitchen. Her mother had started to make tea, but had stopped. The vegetables were still on the chopping board with the knife.

She heard her mother’s voice. She was talking to her father. Just at the moment she was talking, anyway. But there was a note in her voice that was going to rise very soon. She knew the signs. Her mother was doing all the talking. She was talking fast. Her voice was getting louder and louder.

Her father was trying to get her to stop talking. He was failing.

Donna’s mother was talking about something important. Or at least something that was important to her. Donna wasn’t entirely sure what it was. It didn’t really matter, anyway. Sooner or later, once the shouting started, it would get around to the same things. And somehow or other they were all her father’s fault. At least according to her mother. He would deny it strenuously, of course. Then her mother would argue back.

And sooner or later Australia would come into it.

She was eight, when her father had won that competition. Four weeks holiday in Australia. Her mother had been thrilled. She had told everyone about it. At least, she had told everyone that they were going to Australia. She didn’t mention it had been a competition prize. She wanted everyone she knew to think they could afford a holiday on the other side of the world. Donna had been excited, too. Of course, she was. Going somewhere so far away had been a wonderful thought. She hadn’t told anyone, though. Nobody at school knew about it. When they asked where she was going for her holidays she had said something like Brighton, or maybe Blackpool.

But her mother had shopped for hot weather clothes. She had bought sun lotions and hats and shoes. She had spent far too much money, in fact, and there had almost been a row about that. But they were going to Australia. Her mother was far too excited to spoil the mood.

The day had come. They had gone to the airport in a taxi with all their luggage. Her mother had somehow timed it so that almost everyone in the street saw them leaving. She had waved imperiously at them as the taxi rolled down the street.

Then they had got to the airport. They had gone to check in.

And they found out that the tickets were worthless. The company that offered the prize had gone bust. The airline refused to accept them as passengers. While Donna and her mother sat in disappointment in the departure lounge her father had made inquiries and found out that there would be no hotel, either. The company that gave away the prize hadn’t paid the airline for the tickets or the hotel for their rooms.

Her father had been disappointed, but he was philosophical about it. The trip had been free. They hadn’t lost very much money. Only a taxi fare and what had been spent on new clothes and new suitcases and all of that.

Donna was bitterly disappointed. She had been looking forward to a plane journey that took nearly a whole day. She had been looking forward to a whole month in a new country.

But her mother was furious. Right there, in the middle of the departure lounge at Heathrow airport she had begun to shout at her father, blaming him for it all, telling him he should have made sure everything was all right.

It wasn’t his fault. Even if he had checked, the holiday would have seemed to be all right. The company only went bust the day before they were supposed to depart. There was nothing her father could have done.

But her mother didn’t see it that way. She complained at him all the way home in the taxi. It wasn’t as big as the one they had taken to the airport and Donna remembered a suitcase pushed up against her legs until they were numb and her mother going on and on and on and on. That journey seemed to last forever. But at the same time it didn’t last long enough. All too soon they were back in their street, and even more people were there to see them trudge back into the house with their suitcases. In truth, nobody cared. Nobody was pointing fingers. It didn’t matter. But her mother was burning with humiliation. The row that started at Heathrow carried on as soon as they were in the house and went on all afternoon and all evening. Donna had made herself bread and jam and gone to her room and wished the roof would fall in.

And now, two years later, her mother was still rowing with her dad about it. Donna listened and sighed. They were in the hall. That meant she couldn’t even get to her bedroom without going past them and getting dragged into the whole thing. Nothing she ever did was good enough, either. She lacked imagination. She lacked ambition. She would grow up as useless as her father if she didn’t buck her ideas up.

And so on and so on. And she couldn’t bear listening to it one more time. It wasn’t every day, of course. Some days she could come home and tea was ready and everything was fine. But other days, for no reason at all, it would be like this. And it didn’t matter what kind of day she’d had at school. Any feeling of contentment would evaporate as soon as she heard her mother’s voice. If she’d had a bad day she would find no comfort at home.

She turned and looked around the kitchen. Then she moved inexorably towards the chopping board and picked up the knife….

Ben had no comforting images to hold onto. He tried to hang onto Donna’s hand, but as the images whirled around him it started to feel less substantial. He gave a soft cry as he felt himself drawn away from her into his own nightmare.

He looked around at the prison cell he was in. It was lit by a single lamp on the table. There was a warder sitting at a table reading a book. Ben looked at it from where he was lying on the thin mattress with a single blanket over him. It was a bible. He could tell from the cross inlaid into the cover not from the words. He couldn’t read. He never had any use for reading.

An icy fear gripped his heart. There was only one cell where a lamp was lit in the night, and where a warder kept close guard on the prisoner.

He was in the condemned cell.

The warder looked up from his reading and saw that he was awake.

“You’d be better getting back to sleep,” he said. “There’s nothing else for you to do.”

“Why am I here?” Ben asked. The warder looked at him with an indifferent expression.

“If you don’t know by this night, you’ll never know,” he replied. “Go back to sleep. You’ll be woken when it’s time.”

Time… to die.

Ben’s heart felt heavy as lead. He was condemned to hang in the morning. But he didn’t even know why. Hanging was only for capital crimes. He was a thief, no more than that.

Except that one time.

That one time that haunted him forever.

He was twenty-five years old when it happened. He had been in a rich man’s house in Kensington. He had broken into it in the dead of night, but the butler had caught him before he had managed to grab anything of value. In a panic he had hit the man around the head with a silver candlestick and he had gone down with a frightening crash. The man had been alive when Ben escaped through the window, but for weeks afterwards he had been fearful of the consequences. If the butler had died, that would be murder.

The thought that he might have taken a life in the heat of the moment had been bad enough. But the fear of being punished for that foolish and repugnant act was even worse.

But there was no hue and cry as there would be if there had been a death. There were no more policemen in the East End of London than there ever were. There were no inquiries. In the doss houses where he slept or the pubs where he drank beer and ate the cheap but solid food that was provided, there was no speculation about a murderer at large. After a while he began to feel less hunted. But he never stopped feeling sick in his stomach when he thought about what he might have done.

And now he was in the condemned cell, waiting for the morning.

It nearly was morning. There was a greyness to the sky outside the tiny cell window. It was past dawn now. But if it was summer, that was still hours away from the appointed time of execution. Eight o’clock in the morning was that time. He knew that. He had been in Newgate once, when he was seventeen, doing a three month sentence of hard labour after being caught with a gentleman’s pocket watch. There had been an execution. A man who had killed his brother over an argument about a loan of money, or so he had heard from the other prisoners. The day before there had been a quietly restless atmosphere in the prison. Both inmates and warders had been out of sorts. On the morning of the execution, there was a strange silence over the place until a little after eight when the dead bell had tolled and the notice of execution placed on the gate. Before noon, the executed man had been buried within the prison walls and slowly the dull routine of the prison had resumed. But being in that place, on a day when a fellow prisoner had met his end, had shaken Ben, and he had often woken fitfully from his sleep, having dreamt that he was in that condemned cell, waiting for the last morning.

And now he was. And he didn’t even know why. He couldn’t remember anything much at all. He breathed deeply and tried to recall how he came to be convicted. It was a blank. He remembered parts of his life up to now, a rough, hard life of a homeless man who slept where he could, ate when he could, stole what he could to ensure those two essentials of life for a little while. He remembered spells in prison before, the longest a whole year when he was in his mid-twenties. But that had been in Pentonville. They didn’t do executions there. Newgate was the place for that.

So he must be in Newgate, he thought. But he couldn’t remember a trial. He couldn’t remember any sentence. He couldn’t remember being brought here. He couldn’t remember anything before he woke here in this grey dawn with his life measured by a few short hours.

“I didn’t do it,” he told himself. “I couldn’t have done. I’m not a murderer. I’m a thief. I admit that much. I take things to sell, so I can live. But I’ve never killed anyone. I’ve fought other men who want to take the little I have. And I’ve won those fights. I’ve left them bleeding on the dirty cobble stones in dark alleys. But I’ve never killed.

No, not even that butler. The man had survived. He must have done.

But he had never stopped feeling guilty about that, and in his cold, hard nightmares that guilt manifested itself cruelly.

Was this a nightmare, then? Was he dreaming that he was in the condemned cell, waiting to hang?

It didn’t feel like a dream. It felt real. He felt the cold of the cell in the early morning chill. He shivered. It was a real shiver. The echoes of his own breathing in the small cell were real.

He lay there quietly as the hours ticked by. He didn’t say anything else to the warder. He didn’t seem a cruel sort. And he was reading a bible, after all. If he’d asked, he might have read it aloud. But there were too many passages in the bible concerned with punishment and death. It might not be any kind of comfort.

A church bell tolled somewhere. Ben could count to twelve because of church bells tolling the hour. He counted seven. The warder stirred from his reading and looked at him for a brief minute, then he returned to his bible study. Ben wondered if he had been about to say something to him and then changed his mind.

He almost wished the warder would talk to him. He felt so sick in his heart. He would have welcomed the sound of another voice. Even if he spoke harshly to him, it would have been welcome.

The hour passed slowly. Then there were sounds outside the cell. The warder put down his bible and stood up. He told Ben to stand up, too. Ben did so. He wasn’t sure where he got the strength. His legs felt like there was no bone in them. But he did his best.

Two new warders came in. The one who had guarded him through the night nodded silently to them. They took hold of him and led him out of the cell. They flanked him in the corridor, but when they came to the steps one went in front and one behind.

He was taken to the doctor’s room. He had to be passed physically fit to be executed. That was a strange irony. They weren’t allowed to hang a sick man. The examination wasn’t particularly thorough, though. The prison surgeon stood in front of him and looked him up and down and nodded. Then the guards pinioned his hands behind his back. He was taken again down another corridor and out into the empty, echoing exercise yard where the two guards flanked him again. The prison surgeon followed them out. The party was joined by the Chief Warder, the Governor, the chaplain, a sad looking man who avoided the prisoner’s gaze, and two dark clad men who were the executioner and his assistant. They walked slowly towards the execution shed. The chaplain murmured prayers. Ben didn’t really hear them. His own heartbeat was too loud.

The chaplain didn’t go into the shed. Afterwards, he would say a short burial rite over the body, but he wasn’t required to witness the execution. All the others went inside. The trapdoor in the Newgate execution shed was flush with the ground. The drop went down into a pit beneath. Ben stood on the long trapdoor that could take up to four people at once. The principle executioner stepped forward and put a white hood over his head and then the noose….

The Doctor resisted. His mind was stronger than any Human mind. He, too, noted the similarity to the tunnel in the Willie Wonka film. He remembered seeing that film with Jo, in 1971, when it was new. When he was an exile on Earth. At the time he had been angry and frustrated and filled with a sense of betrayal because his own people had done that to him. But when he looked back at that hiatus in his life he thought of it as a happy time. He had made a lot of good friends. Liz, Jo, the Brigadier. Of course he had fought with the Brigadier half the time. They differed ideologically. But he was still a good friend.

He held onto those reassuring memories of unbroken friendships. They stopped him succumbing to the nightmares. He recognised at once that the images whirling around him were being drawn from his own memory. He saw all of his regenerations replaying in painful detail. But although these were memories that could wake him in the night in a cold sweat, that was when the memories were in his own head and he felt the burning pain of regeneration in his very core. This was like watching it happen to somebody else. It was distressing. But it didn’t hurt him any more than remembering those events always hurt.

Then he watched his planet explode into a ball of fire. Those images hurt a lot. Yes. They did. But watching it like this was still far less distressing than seeing it happen inside his own head. He could handle it.

He closed his eyes, shutting out the images. He focussed his mind inwardly, first, clearing his own thoughts, banishing the negative emotions that had been brought to the fore. Then he reached out and felt the minds around him. There were some two dozen people in all, and each of them was experiencing intensely disturbing nightmares even though none of them was asleep. It was a kind of hypnotism, of course.

He opened his eyes and looked around the dim room, making out the people, all standing very still and quiet, despite what was happening in their heads. He looked at the swirling images and saw that they were just random patterns of light and shade. His own memories, his own imagination had made them into something else. But now he had sorted himself out he could see it all for what it was.

Donna and Ben were affected. The Doctor looked at them both and felt guilty. He brought them into this place and the mental tortures they were suffering were a result.

But at least he could do something about that.

He put his hands around Ben’s head first and gently reached into his nightmare.

Ben did his best not to make any kind of sound as the noose was put around his neck. He didn’t want to sound like a coward. Even so, he was more frightened than he had ever been in his life. He wondered how much longer it would be before the lever was pulled and he would drop into the pit, the noose breaking his neck cleanly – as witnessed and noted by the surgeon.

Then the noose was pulled off again. The hood was pulled away. He felt his hands free, suddenly. He looked around. The prison officials were standing as still as statues, unblinking, unseeing. Only one person moved. The Doctor took hold of Ben’s hand and gently moved him off the trapdoor.

“We’ll talk about this later,” he said. “But let’s go and get Donna. She needs us.”

“Donna?” Ben looked at The Doctor and blinked as he remembered. “Yes. Donna… But Guv’nor, how do we get out of here. It’s a prison…”

Only it wasn’t. Not now. It was the kitchen of a house in Chiswick. Ben looked around in surprise. Then he saw The Doctor move slowly but purposefully towards the girl in school uniform who was reaching to pick up a sharp knife from the counter.

“No, Donna,” he said, staying her hand as Ben slipped past them and put the knife safely back in the drawer. “It never happened like that. You never would do it. Come on back with me and Ben, now.”

The girl looked at The Doctor in surprise. At first she didn’t know who he was. Then her lips moved silently around the word ‘Doctor’ and tears pricked her eyes. The Doctor hugged her briefly and then let Ben take hold of her hand. The child version of Donna in the dream seemed surprised that an adult who wasn’t a relative was holding her hand, but only momentarily. Then the adult Donna looked at The Doctor and at Ben and then at the kitchen around her.

“We’re done here,” The Doctor said very simply.

And the next moment they were back in the dimly lit House of Nightmares on the North Pier. The random patterns were still swirling but neither Donna nor Ben saw anything disturbing in them now.

What did disturb them was the sight of so many other people around them who were going through their own terrors.

“Go to each one,” The Doctor said. “Touch them on the forehead. The physical contact will allow you into their nightmares. Bring them out of it again.”

To demonstrate, he reached and touched a young woman on the head. He saw in his mind’s eye her horror of being trapped in a room full of very large spiders. He took her hand and drew her across the floor to the door that he had opened. She opened her eyes back in the real world and looked at The Doctor in surprise. He reached into his pocket for his sonic screwdriver and aimed it at a portion of the wall. It opened up into daylight.

“Exit door over there,” he said to the woman. There’s a café open at the bottom end of the pier. Get a cup of tea and don’t worry about anything. It’s all over now.”

The woman did as he said. Donna and Ben watched her go and then hurried to do as he suggested. Donna helped a middle aged man escape from a burning building by appearing with a bucket of water that inexplicably doused the whole fire – dreams are not logical, of course. Ben helped another young woman find a path through a beach full of peculiarly aggressive crabs. One by one they showed the victims of the nightmares how to wake up and then sent them on their way for a pot of tea and a sit down.

The Doctor made his way through the crowd, pausing to wake a woman whose nightmare was that she had lost her child and a child who had lost her mum. In reality they were stood right next to each other, but it needed him to put their hands together and make them realise that. He sent them away and then strode towards an inner door that he had spotted with his sharp alien eyesight. The sonic screwdriver opened it easily. He stepped into a small room that was half office, half ride operating equipment, and half again a makeshift sleeping quarters for the small, hunched up Human he found within.

And yes, he knew that was three halves, and what he should have been thinking of, to be strictly accurate, was three thirds. Then again, the thin mattress with a pillow and one blanket on it hardly warranted a whole third of the equation. It was more like …

Well, never mind what the fraction was. The real issue was that the man obviously did a lot of work and not much sleeping and he did it all in this dingy little room.

“Professor Soon, I presume?” The Doctor said. “I’m The Doctor and I’m your worst nightmare.”

“I should be so lucky,” replied the Professor. “You have no idea what my worst nightmare is.”

He didn’t resist in any way when The Doctor leaned over and pressed a switch that turned off the whirling lights in the nightmare room and another that switched on ordinary lights. On a large monitor The Doctor saw Donna and Ben waking the last of the victims and ushering them towards the exit. When everyone was gone they turned and looked at the door The Doctor had gone through and very presently joined him.

“Professor Soon was just about to tell me about his worst nightmare,” he said to them as they flanked him like able lieutenants.

“Well, it couldn’t be any worse than mine,” Ben responded. “Or some of those poor people out there. There was a woman who…”

“My nightmare is with me, waking or sleeping,” Professor Soon answered. “I can never be free of it. And it isn’t content with haunting me. It has to take the nightmares of others, too.”

“Hence Professor Soon’s House of Nightmares,” Donna noted.

“Nobody was harmed,” he insisted. “They won’t even remember. They will think they were in some kind of ‘haunted swing’ ride. The creature feeds on the nightmares. That is all. It needs them.”

“What creature?” The Doctor demanded.

“This one,” Professor Soon replied. He closed his eyes. Donna and Ben instinctively recoiled as his face shimmered like a bad effect from a sixties science fiction programme and transformed into something vaguely humanoid, but something like a reptile, a bird and a fish at the same time. It spoke in a hissing voice like some combination of those three creatures might do if given a voice.

“You have freed the cattle who came willingly to be milked by me. Now I shall feast on you until you die. I shall make your nightmares last for an eternity. Or what feels like an eternity in your suffering.”

“Ben,” The Doctor ordered. “Recite the alphabet, the way Donna taught you. Don’t think of anything else but that. Forwards and then backwards. Keep going. Donna, sing something. It doesn’t matter how badly. Think of a song and sing it. Concentrate on the lyrics. Keep singing it.”

Ben was startled, but he did as The Doctor told him, loudly and quickly. Donna began to sing the ‘Golden Ticket’ song from Willie Wonka. She got most of the lyrics right. When she didn’t, she made some up.

The Doctor, meanwhile, thought happy thoughts. And yes, he knew that was a cliché. But with Ben and Donna filling their minds with the alphabet and singing, he knew the creature would concentrate on him. It wouldn’t be able to get into their minds. Donna had almost managed it before. Thinking about that film with its jolly songs and colourful images of sweets and chocolate and happy endings had stopped her from succumbing to the nightmares for much longer than the others around her.

The Doctor thought again of the time when he went to see that film with Jo. He had felt a bit like her favourite uncle taking her on a treat. He had bought sweets and popcorn and fizzy drinks and they had shared them as they watched the film. It had been a delightful break from being U.N.I.T.’s special scientific advisor and it had solidified his special friendship with Jo, his favourite of all the fledglings who ever came under his metaphorical wing.

He thought of other happy times in his life. There had been plenty of them, even though there was an unfair proportion of angst as well. He remembered his first romantic kiss, with a young female Time Lord candidate in a shady corner of the quadrangle in the Prydonian Academy. And that image slid neatly into remembrance of other kisses from attractive young women of various sorts, though mostly either Time Lord or Human, given his long association with both of those kinds. He lingered over the memories of the few women he had truly loved and enjoyed more lasting passions with. His first wife, whose face and voice he could still retrieve from his memories when he wanted to; the briefly wonderful time he had with Rose; the even briefer flirtation he had with Reinette du Poisson and a few other women who had made his hearts soar in that way; the blissful lifetime he spent with Dominique. In a thousand years he had not exactly set the universe on fire with his love life. But he had his moments and they were all wonderful.

A stray thought came into his head on the back of those memories. He recalled the time Jack Harkness had kissed him. It had been brief. It had definitely not been solicited. And he often denied that it had happened at all, even to himself. But the memory was a sweet one. It had been an unconditional show of affection and it had lightened his heart at that terribly tense time.

He laughed out loud as he remembered his own shocked amazement at what rated as the most unexpected kiss of his whole life. He focussed on it. He felt the creature recoil from the joy in his hearts and the happy images in his mind. It couldn’t break into his mind while he was so happy. It couldn’t force him to relieve nightmares.

And so it was weakening. The Doctor laughed even louder and thought good, warm thoughts for Jack Harkness in whatever he was doing now and instead of merely defending himself from attack he went onto the offensive. He found the creature’s mind, piggy backed on the mind of the hapless Professor Soon. He poured his happy memory of unconditional love into the creature’s mind. He poured his memory of every kiss he ever received from woman or man, or some rare beings that were both or neither one nor the other. He poured his fatherly feelings for Jo and Vicki and Ace, and all the other young women who had filled his life, his love for Susan, his own blood kin who they had replaced. All of those were his barriers against despair. And they were his weapons against a creature that despised happiness and preyed on that despair.

He didn’t laugh when the creature gave a strangled cry and its features disappeared in another bad special effect. He knew he had killed it. And that wasn’t something he ever did lightly. But Professor Soon looked happy. He breathed deeply and held his head up. He looked taller now he wasn’t hunched and scared. And he looked very grateful to The Doctor.

“You can stop singing now,” he told Donna. “Ben, you can stop, too. It’s over.”

“Thank goodness,” Donna said. “My throat was getting sore.”

“We’ll go and see if there’s a table free in that café in a minute,” The Doctor assured her. “Professor Soon, if that is your name. You were lucky. Nobody was permanently hurt by your insane scheme, including you. Shut up this operation and go away. Make something worthwhile of your life and be careful not to get mixed up with things of the occult again.”

With that he turned and put his hands on his friend’s shoulders and turned away out of the room. They all stepped out through the door and were surprised to see that the sun had broken through the clouds even thought it was still drizzling with rain. They admired a vibrant rainbow that disappeared in the general direction of the Isle of Man and walked back down the pier to the café that had enjoyed an unexpected surge in customers. They recognised them all, but the customers didn’t seem to recognise them. Professor Soon was right about them forgetting. Which was fine. Nobody was hurt in the end. But it was certainly something The Doctor had to put a stop to.

By the time they’d had tea and a plate of toast the rain had stopped altogether. They strolled along that part of the promenade called the Golden Mile in sunshine before coming to a shelter and sitting for a while. There were things to talk about.

“I never really touched a knife, in reality,” Donna was at pains to assure both Ben and The Doctor after she had explained in more detail what her nightmare was about. “There were lots of days like that. But I never really was THAT desperate. Was it the creature making things feel worse for me? Driving me to think that way?”

“I think so,” The Doctor replied. “Do you often dream about it? Being trapped as a child with your parents rowing?”

“Yes,” Donna admitted. “Is there something deeply Freudian about that?”

“Nuts to Freud,” The Doctor told her. “He told me I had a multiple personality disorder. You aren’t trapped, Donna. You can make your own choices. They include finding ways of relating to your mum that don’t allow for her to criticise you and for you both to remember that underneath all the friction you do love each other.”

“That sounds like Freudian stuff to me.”

“No, it’s Doctor stuff.”

Donna and The Doctor both looked at Ben. He was unhappy.

“You don’t have to talk about it if you don’t want to,” The Doctor assured him. “It can remain between you and me. And I won’t press you about it.”

“No,” he answered. “I should tell you. I should especially tell you, Donna. I have hoped that you and I… but you should know the whole truth about me, about the shame I have never confessed to you.”

He told them both about the burglary in Kensington and the butler who he had hit. Donna was shocked by that revelation, but she didn’t recoil from him as he might have expected her to do. And when he told her of his fear, and the guilt he had carried with him, the guilt that had manifested itself in that so terribly vivid nightmare, she gripped his hand reassuringly.

“You were sorry for what you did,” Donna told him. “So it’s not so bad, is it, Doctor?”

“It’s a serious thing to do,” The Doctor said in a cool voice. “You were lucky to get away with it. Burglary with GBH is taken seriously in any era. I certainly can’t condone it. But you’ve punished yourself for longer and more harshly than the penal system of your time would have done. Even ten years with hard labour wouldn’t have been so painful as reliving it in your dreams like that. Consider yourself punished for your actions, Ben. You’ve got your ticket of leave now, and you’re well on the way to rehabilitating yourself. So no more guilty feelings.”

“But what if I did kill him?” Ben asked. “If I did… I would deserve to pay with my life.”

“I don’t think you did,” Donna assured him. “You’re not a murderer, Ben. I’m sure of it. Anyway, you didn’t mean it. At the worst, it’s manslaughter.”

“No,” The Doctor contradicted her. “Even though he didn’t mean it, if he had killed the man while in the act of burglary, it would be considered murder under almost any statue I can think of. Believe me. I’m a lawyer. But I think we need to put Ben’s mind at rest. Come on.”

He brought them back to the TARDIS, which was parked near the front entrance to Blackpool Tower. Ben and Donna both sat quietly as he programmed a very quick trip to Victorian London.

The TARDIS materialised in the affluent Kensington street that The Doctor had read in Ben’s memory. He told Ben and Donna to stay by the TARDIS as he stepped out and walked across the road. He went right up to the door of the tall, well appointed town house and rang the bell. Presently a butler answered the door. The Doctor had obviously acted like somebody who had the wrong house and the butler came out onto the step to give him directions to the correct address. Donna saw Ben gasp with relief. He recognised the man he had attacked. He was alive.

“This is afterwards?” Ben asked as The Doctor returned to the TARDIS and ushered them both back inside. “After the burglary…”

“Yes, it is,” The Doctor answered. “When I shook hands with him, I was able to read his mind very quickly. He has a memory of being hit by a burglar who fled the scene. He doesn’t remember a face, only being revived by the master of the house who came to find out what the noise was. As I said before, Ben, you were VERY lucky. So was he. And… we’ll say no more about it, I think.”

The Doctor looked at Donna. She was sitting beside Ben, looking at him thoughtfully. The two of them had grown close. It wasn’t exactly a whirlwind romance between them. They were both a little too world weary for that. It was something more solid and dependable. But Ben’s admission of what was, there were no two ways about it, a serious crime in his past, could threaten that. It blew apart Donna’s notion of him as a kind of grown up Oliver Twist, more sinned against that sinning. She had to realise that he had a past that was dark and unpleasant. She had to get around that before they could go forward into any deeper relationship.

She reached and took his hand. With her other hand she reached and stroked his clean shaven face and pushed back a lock of neatly cut hair that nevertheless always managed to fall over his forehead. He didn’t look like a Victorian thief and burglar any more. He looked respectable enough to introduce to her mother, although she was putting off doing that for as long as she possibly could.

“The Doctor’s right,” she said. “We’ll say no more about it.”

Ben’s relief was visible not just in his face, but his whole body. The Doctor smiled and went to the console.

“I’m taking us back to Blackpool,” he said to them. “We never got to see any of the sights properly.”

Neither answered him. He looked up and noticed that they were occupied. He looked back at the console and concentrated on finding a summer’s day when it wasn't raining.

|

|

|